I met Peter in 1981, but really in 1970 when I was searching for a location to direct a short film on Virginia Woolf for public television. I didn’t have the money to go to England, so I was looking for a place that could be evocative of Woolf’s outer and inner landscape. Following a hint, I drove to Montauk where I found a gray-shingled house built around a lighthouse. No one was home but when I peered through a window I saw that the lighthouse had been turned into a library, a three-story cylinder circled by windows on a coastline that could be seen as a moor, the ocean beyond. No one was there but a neighbor told me the house was rented by four young men, photographers they believed. I might find them in a café downtown.

They didn’t hesitate. “Sure, no problem,” and, on a cloudy day in November, with actress Marian Seldes, along with camera and sound people Alan and Susan Raymond and my associates in public television, we shot the film. The finished film went on to have a good life, winning awards and contributing to my getting a grant to travel to England and meet the last surviving members of Bloomsbury. But that is another story. In the intervening years, I tried to show friends that magical house but I could never find it again.

In 1981, I was directing Writers in Performance, a literary series at the Manhattan Theatre Club where I experimented and produced different ways to present the written word on stage.

I had adapted the writings of Isak Dinesen and secured the actress Zoe Caldwell to read the script at St. Peter’s Church on Lexington Avenue, a space that was and is stunningly white, angular, and dramatic. The Church, which defined its mission as a place for the arts, said yes to my request. Caldwell would stand on the pulpit; on either side tall walls soared, a perfect place to project Peter Beard’s images of Dinesen whom he knew well and of the Africa they both loved.

I didn’t know Peter — I almost don’t know the young woman I was then, impassioned and thus bold — but when I asked to visit him, he said yes. One aspect of this story is how different life was then, far more open and possible. His apartment had a mezzanine filled with technical equipment; his living space below was spare, a stopping-off place for Peter and his then-wife, model Cheryl Tiegs. Peter and I hit it off right away. I would like to think I was special but Peter was, I think, always genial, accepting, and enthusiastic. He was then and throughout our long friendship (never romantic) a thoroughly good guy. We looked at his photos, talked about any number of things and he said yes to my projecting his images very large on those tall white walls flanking Caldwell. My hope had been to be able to create dissolves from one photograph to another, the images alternating from side to side. If I’m remembering correctly, that idea didn’t work — the technology wasn’t up to it — but everything else did work. The audience gasped when Dinesen in that fabulous gaunt portrait of Peter’s appeared huge on the wall.

Afterward, a group of us went out for dinner. I remember Carol Houck Smith, my legendary editor from Norton, sat on one side of the table, Peter at its head. Carol asked Peter what was dearest to him from his entire body of work. “My diaries,” he said. “But I lost them when my house in Montauk burned down.” He went on to talk about what that house and its loss had meant to him. It was a moment, with all due respect to the aptness of cliché, that could be compared to a flash of lightning, or an electric bulb above my head or, simply, a revelation. “Peter,” I said, “was your house built around a light house with a library . . .” and I went on to describe the house, its vanishing now explicable. It was true. My film was the only record of Peter Beard’s famous (and in Warhol circles, infamous) long-lost paradise. We planned for a time when I would show it to him.

But first an idea took hold of Peter. He thought that I looked like Ava Gardner (pacem, time, the river, and an artist’s imagination). He wanted to photograph me as Ava. He set up an appointment at Leonard’s of London , a.k.a. Leonard’s of Mayfair in its English incarnation where the clientele included an extraordinary range of celebrities, from Twiggy and David Bowie to President John F. Kennedy. I think that Peter told me that Leonard had recently done Lady Diana’s hair for her wedding to Prince Charles.

It was my lunch hour. I had sandwiched the photo shoot in the midst of my day job as program officer at the New York Council for the Humanities housed at the CUNY Graduate Center on West 42nd Street. I walked to the salon carrying a dress I’d found in my closet that I thought might be appropriate for Ava, vintage with good decolletage (that was before my bout with breast cancer, so Peter’s photographs might be the last record of me with a low-cut neckline). Peter approved and with great concentration supervised my make-up and the styling of my long hair. He was ready to shoot. I looked in the mirror … and I looked in the mirror. Waiting for Peter to begin. I needed a tutorial. “Move around,” he said. “That’s how models do it.” I shook out my hair as I turned my head in various directions, Peter circling around me, snapping all the while.

After an hour, I had to go back to my job, still in Ava dress and make-up. My office mates were wowed. “You must…“ they said, urging me to call my then-boyfriend (later my husband) who worked around the corner. “Steve has to see you this way.” He took one look at me and passed judgement. “I hate it.” I had wanted something quite different — surprise with an acknowledgment of beauty — but I had what we would now call self-esteem issues. I took his response to heart, thinking that perhaps I looked tarted up. Years later I asked Steve why he hated how I looked that day. His answer — a sweet one — was, “It wasn’t you.” When Peter sent me a large manila envelope with four or five pages of contact prints, each page with — give or take — 36 portraits of me as Ava, some of them circled by Peter in red pencil as his favorites, I thanked him, and put the envelope in a drawer where I put much else in those years, including my writing which I also thought wasn’t good enough. Those contact sheets are still there, moving with me from New York to California, virtually never seen.

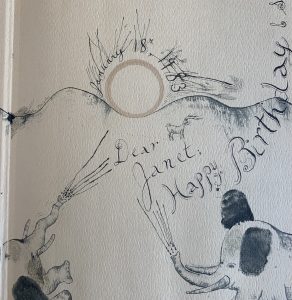

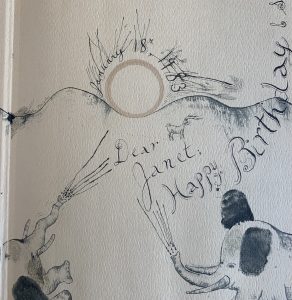

Peter and I stayed in touch — for a birthday, he gave me a first edition of Longing for Darkness with his drawings and a wonderful dedication. From time to time, we spoke on the phone — one of those genial calls from him, or when I phoned him, “Hey Janet,” his voice infused with enthusiasm, as though the most wonderful thing had happened. Later I heard about his 1996 accident when he was attacked by an elephant and suffered terrible — really horrifying — injuries. They were of an order that would have downed many less spirited people. Peter kept on.

Fast forward to 2016. I still hadn’t shown him the film. Sometimes I can take a very long time, carrying guilt all the while. I had transferred the old tape to a DVD and phoned him before a trip to New York. He invited me to come visit. His building across the street from Carnegie Hall was one of the old grand ones, its lobby with gold finish on bannisters and elevator. I was impressed, nervous (I was no longer Ava), and expecting an equally grand apartment. At the door, I was greeted by a woman in street clothes, Peter’s in-home caregiver who sat beside the bed during Peter’s and my time together. Peter, supine, said on seeing me, “Hey Janet!” On his bed were files — long cardboard boxes, open and packed with vintage snapshot-size photographs. He explained that he was going through them to put them in order. Peter picked up one and then another, showing them to me and telling me little stories about where they’d been taken. But often he wasn’t clear. Whether it was a stroke or incipient dementia, Peter — the handsome, no, the beautiful — was not himself. But then again, he was, partly. It was clear that he adored his daughter, showing me photos he’d taken of her.

Together we went into an adjoining room, his aide at his side. I gave him a little background, about his house, and our story. I slid in the disc. Up on the small screen came Marian Seldes in an old cardigan that Virginia Woolf might have worn. She was sitting at a desk, looking directly into the camera. To Seldes’s image, Peter spoke. “You still look like Ava Gardner.” I felt a familiar tightening in my chest that I associate from childhood with sadness. I thought then it was my heart; now I think it’s my esophagus. No matter. At that moment, it was my heart. Peter recognized the hallway in his old house, and, I believe, the library with its three tiers of windows and spiral staircase. It was supposed to be an image of Virginia Woolf’s mind, now of Peter’s mind. Mine too.

This account is the record of a fifty-year friendship. I’m not sure I have the right to call it a friendship, there were too many gaps for that. Five decades of sustained connection, from 1970 to 2020, the year of his death. I feel his loss. I want him to be in the world. Not just my world, but the world in which he was a valiant wizard who, with a wave of his camera, transformed me, and so many others.

Janet Sternburg is a writer and fine arts photographer. Recent books include White Matter: A Memoir of Family and Medicine (Hawthorne Books) and the monograph Overspilling World: The Photographs of Janet Sternburg (Distanz Verlag, Berlin).

They didn’t hesitate. “Sure, no problem,” and, on a cloudy day in November, with actress Marian Seldes, along with camera and sound people Alan and Susan Raymond and my associates in public television, we shot the film. The finished film went on to have a good life, winning awards and contributing to my getting a grant to travel to England and meet the last surviving members of Bloomsbury. But that is another story. In the intervening years, I tried to show friends that magical house but I could never find it again.

In 1981, I was directing Writers in Performance, a literary series at the Manhattan Theatre Club where I experimented and produced different ways to present the written word on stage.

I had adapted the writings of Isak Dinesen and secured the actress Zoe Caldwell to read the script at St. Peter’s Church on Lexington Avenue, a space that was and is stunningly white, angular, and dramatic. The Church, which defined its mission as a place for the arts, said yes to my request. Caldwell would stand on the pulpit; on either side tall walls soared, a perfect place to project Peter Beard’s images of Dinesen whom he knew well and of the Africa they both loved.

I didn’t know Peter — I almost don’t know the young woman I was then, impassioned and thus bold — but when I asked to visit him, he said yes. One aspect of this story is how different life was then, far more open and possible. His apartment had a mezzanine filled with technical equipment; his living space below was spare, a stopping-off place for Peter and his then-wife, model Cheryl Tiegs. Peter and I hit it off right away. I would like to think I was special but Peter was, I think, always genial, accepting, and enthusiastic. He was then and throughout our long friendship (never romantic) a thoroughly good guy. We looked at his photos, talked about any number of things and he said yes to my projecting his images very large on those tall white walls flanking Caldwell. My hope had been to be able to create dissolves from one photograph to another, the images alternating from side to side. If I’m remembering correctly, that idea didn’t work — the technology wasn’t up to it — but everything else did work. The audience gasped when Dinesen in that fabulous gaunt portrait of Peter’s appeared huge on the wall.

Afterward, a group of us went out for dinner. I remember Carol Houck Smith, my legendary editor from Norton, sat on one side of the table, Peter at its head. Carol asked Peter what was dearest to him from his entire body of work. “My diaries,” he said. “But I lost them when my house in Montauk burned down.” He went on to talk about what that house and its loss had meant to him. It was a moment, with all due respect to the aptness of cliché, that could be compared to a flash of lightning, or an electric bulb above my head or, simply, a revelation. “Peter,” I said, “was your house built around a light house with a library . . .” and I went on to describe the house, its vanishing now explicable. It was true. My film was the only record of Peter Beard’s famous (and in Warhol circles, infamous) long-lost paradise. We planned for a time when I would show it to him.

But first an idea took hold of Peter. He thought that I looked like Ava Gardner (pacem, time, the river, and an artist’s imagination). He wanted to photograph me as Ava. He set up an appointment at Leonard’s of London , a.k.a. Leonard’s of Mayfair in its English incarnation where the clientele included an extraordinary range of celebrities, from Twiggy and David Bowie to President John F. Kennedy. I think that Peter told me that Leonard had recently done Lady Diana’s hair for her wedding to Prince Charles.

It was my lunch hour. I had sandwiched the photo shoot in the midst of my day job as program officer at the New York Council for the Humanities housed at the CUNY Graduate Center on West 42nd Street. I walked to the salon carrying a dress I’d found in my closet that I thought might be appropriate for Ava, vintage with good decolletage (that was before my bout with breast cancer, so Peter’s photographs might be the last record of me with a low-cut neckline). Peter approved and with great concentration supervised my make-up and the styling of my long hair. He was ready to shoot. I looked in the mirror … and I looked in the mirror. Waiting for Peter to begin. I needed a tutorial. “Move around,” he said. “That’s how models do it.” I shook out my hair as I turned my head in various directions, Peter circling around me, snapping all the while.

After an hour, I had to go back to my job, still in Ava dress and make-up. My office mates were wowed. “You must…“ they said, urging me to call my then-boyfriend (later my husband) who worked around the corner. “Steve has to see you this way.” He took one look at me and passed judgement. “I hate it.” I had wanted something quite different — surprise with an acknowledgment of beauty — but I had what we would now call self-esteem issues. I took his response to heart, thinking that perhaps I looked tarted up. Years later I asked Steve why he hated how I looked that day. His answer — a sweet one — was, “It wasn’t you.” When Peter sent me a large manila envelope with four or five pages of contact prints, each page with — give or take — 36 portraits of me as Ava, some of them circled by Peter in red pencil as his favorites, I thanked him, and put the envelope in a drawer where I put much else in those years, including my writing which I also thought wasn’t good enough. Those contact sheets are still there, moving with me from New York to California, virtually never seen.

Peter and I stayed in touch — for a birthday, he gave me a first edition of Longing for Darkness with his drawings and a wonderful dedication. From time to time, we spoke on the phone — one of those genial calls from him, or when I phoned him, “Hey Janet,” his voice infused with enthusiasm, as though the most wonderful thing had happened. Later I heard about his 1996 accident when he was attacked by an elephant and suffered terrible — really horrifying — injuries. They were of an order that would have downed many less spirited people. Peter kept on.

¤

Fast forward to 2016. I still hadn’t shown him the film. Sometimes I can take a very long time, carrying guilt all the while. I had transferred the old tape to a DVD and phoned him before a trip to New York. He invited me to come visit. His building across the street from Carnegie Hall was one of the old grand ones, its lobby with gold finish on bannisters and elevator. I was impressed, nervous (I was no longer Ava), and expecting an equally grand apartment. At the door, I was greeted by a woman in street clothes, Peter’s in-home caregiver who sat beside the bed during Peter’s and my time together. Peter, supine, said on seeing me, “Hey Janet!” On his bed were files — long cardboard boxes, open and packed with vintage snapshot-size photographs. He explained that he was going through them to put them in order. Peter picked up one and then another, showing them to me and telling me little stories about where they’d been taken. But often he wasn’t clear. Whether it was a stroke or incipient dementia, Peter — the handsome, no, the beautiful — was not himself. But then again, he was, partly. It was clear that he adored his daughter, showing me photos he’d taken of her.

Together we went into an adjoining room, his aide at his side. I gave him a little background, about his house, and our story. I slid in the disc. Up on the small screen came Marian Seldes in an old cardigan that Virginia Woolf might have worn. She was sitting at a desk, looking directly into the camera. To Seldes’s image, Peter spoke. “You still look like Ava Gardner.” I felt a familiar tightening in my chest that I associate from childhood with sadness. I thought then it was my heart; now I think it’s my esophagus. No matter. At that moment, it was my heart. Peter recognized the hallway in his old house, and, I believe, the library with its three tiers of windows and spiral staircase. It was supposed to be an image of Virginia Woolf’s mind, now of Peter’s mind. Mine too.

This account is the record of a fifty-year friendship. I’m not sure I have the right to call it a friendship, there were too many gaps for that. Five decades of sustained connection, from 1970 to 2020, the year of his death. I feel his loss. I want him to be in the world. Not just my world, but the world in which he was a valiant wizard who, with a wave of his camera, transformed me, and so many others.

¤

Janet Sternburg is a writer and fine arts photographer. Recent books include White Matter: A Memoir of Family and Medicine (Hawthorne Books) and the monograph Overspilling World: The Photographs of Janet Sternburg (Distanz Verlag, Berlin).

LARB Contributor

Janet Sternburg is the author of White Matter: A Memoir of Family and Medicine(Hawthorne Books, reviewed in LARB here). Her previous memoir, Phantom Limb (American Lives, University of Nebraska) is also at the intersection of personal life and neuroscience. Other books include Optic Nerve: Photopoems (Red Hen Press) and the two volumes of The Writer on Her Work (W.W. Norton). A fine art photographer. Sternburg has exhibited her work in solo shows in Berlin, Korea, New York, Mexico, Los Angeles, and Milan. Her photography publications include Aperture and two monographs, both published by Distanz Verlag (Berlin): Overspilling World: The Photographs of Janet Sternburg (2016), and this month, I've Been Walking: Janet Sternburg Los Angeles Photographs (September, 2021).

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F04%2FPeter-Beard-1.png)