“You Couldn’t Even See”: Genre, “Thomasine and Bushrod,” and the Matter of Black Film

By Nicholas ForsterApril 21, 2021

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2021%2F04%2FForsterBlackFilllm.png)

WITH MOVIES MORE readily accessible than ever before, it is easy to get lost in possibility. Choices abound: perhaps it is time to watch some classic that you always wanted to see, or maybe, tonight you’ll dig into rewatching a film you love, or it might just make sense to check out that groundbreaking recent release that everyone is talking about. Amid the plenitude, there is that oh-so-common feeling some have called “analysis paralysis.” Genres serve a sorting function, a kind of classification that helps us make sense and aid our viewing habits. As a kid, I roamed Blockbuster’s library, overflowing with filmic lives encased in frosted and faded VHS and DVD containers. I ambulated the store’s perimeter, looking through the temporal category of “New Releases” before weaving in and between the lettered aisles, delineated by genre markers. These categories are historically defined and ever-changing, but to make use of genres, there must be some kind of trust or relationship between the viewer and external classifications. As slippery as the terms of ordering may be, they remain significant by setting up expectations. Where things get especially tricky, though, is in how advertisers, retail outlets, and studios classify something like “Black film.” In his groundbreaking 2016 book, Film Blackness: American Cinema and the Idea of Black Film, Michael Boyce Gillespie beautifully writes that the notion of “Black film is always a question, never an answer.” To raise that question, there must be some trust in the significance of the terms and their power.

In the wake of this past summer and the police killing of George Floyd, film companies and streaming services mobilized the rhetoric of “Black Lives Matter” for proprietary possibilities to insist on something like “Black Movies Matter.” These calls sought to create confidence that there was some corporate accountability and awareness of what was going on in the country. Even as this is a corrective to racist canonical histories, what remains unclear here is what it means to matter: how might such a claim relate to the omnipresence of anti-Black violence, which resides at the foundation of the modern world? Do these films matter in the sense that they are of aesthetic importance or political significance? If so, how does a cycle of production like Blaxploitation (1970–1976), in which Black artists often starred in films produced for the gains of white investors, promote a mattering that, well, matters? While there is a connection between these calls and the recent deluge of anti-racist reading lists, the streaming services’ categorizations are a bit different, a bit more nuanced, less driven by the moment and more historically oriented. Nevertheless, watching a movie might change your life, but watching a film from the 1970s won’t save another’s.

In the late ’70s, amid the rise and fall of Blaxploitation, scholar Thomas Cripps sought to mark out what it would mean for Black film to be a genre. Film studies as a discipline was still in its infancy, and semiotics, ideological critique, and psychoanalysis provided popular methodologies to adjudicate and interpret movies. Bringing these together, Cripps’s gambit was to suggest that Black film “ritualizes the myth of winning” by “celebrat[ing] aesthetique du cool,” whereas Blaxploitation films merely turned to “sneering and bravado.” Designating Black film as a genre, Cripps registered the significance of ritual viewing experiences that contained a set of internal codes and alternative scripts hailing different audiences. Comparing Black film to “black magazine[s] that [print] soul food recipes, or the black student newspaper[s] […] featur[ing] a glossary of black argot,” Cripps claimed that Black films represented the “uses and beauties” of “black identity.” Here, genre brought with it a faith in the beauty of Black life.

Still, Cripps played into a game of legitimation and meaning. Where the category “Black film” offered a mythic landscape of “soul,” Blaxploitation, with its supposed financially motivated digestibility, was about “shrill imitation.” To imitate, for Cripps, is to be inauthentic, untrustworthy. Over the last year, a similar set of evaluative moves have emerged as the film industry comes to terms with its own sense of hierarchies regarding Black art. Streaming services proclaim a recognition of Black film worlds while (particularly white) critics, seemingly eager to right the wrongs of the past, jump in to champion work by Black filmmakers. Of course, an identity is not the same as a positionality, nor do shared identities necessitate shared aesthetic or political investments. While debates about what constitutes “Black Art” have been complicated and importantly waged over the last century, the recent turn backward, to a history of “Black Films” that matter, marks a difficult renegotiation over how characterization can limit even as it seeks to expand.

Gordon Parks Jr.’s 1974 film Thomasine and Bushrod allegorizes the tangled knot of genre, race, and film by suggesting that media characterization and its attempts to classify can’t quite acknowledge the intricacy of Black life. While the film has been available online for some time, Thomasine and Bushrod was recently added to the Criterion Channel and was inserted into the prestige service’s “Black Westerns” collection. This collection revises Thomasine and Bushrod’s original reception, ever so slightly. It was first released two years after Parks’s smash hit Superfly, and critics have often framed it as a Blaxploitation film. Now, it bears the weight of a different, albeit still problematic, classification of “Black Western.”

Set in Texas at the spatial frontier of a nation in the early 1910s (prior to New Mexico and Arizona being colonially annexed into the United States), where the supposed emergence of the twin marvels of the automobile and the train marked ongoing industrialized modernization, the generic description promises some descriptive coherency. Alongside this classification is a thornier language of comparison: critics, industry mags, and advertisers have framed Thomasine and Bushrod as a Black version of some white film. In 1974, the critic Tom Stokes called the movie “a darker Butch Cassidy,” a sense of shading animated less by any shared themes than by the visibility of race. In 2021, Criterion described Thomasine and Bushrod as “Blaxploitation’s answer to Bonnie and Clyde.”

But what is the question, posed by Arthur Penn’s film, that Thomasine and Bushrod answers? Both of these descriptors rely less on the stuff of the film and more on the logics of comparison, which act as shortcuts to draw a relationship, without probing the significance or the specifics of how Parks’s film complicates any generic delimitation. Those descriptions fail as much now as they did nearly half a century ago.

Thomasine and Bushrod is as much about the travails of remarriage and the ragged ways people express love as it is about the mythic space of “the West.” Rather than reinforce these classifications, it feels more adequate, whatever that might entail, to engage on the terms that Max Julien (the writer and lead actor), Gordon Parks Jr. (the director), and Vonetta McGee (the co-lead and Julien’s partner at the time) offer. Bushrod, played by Julien, is a lover — of life, of fugitivity, of the world around him. He is introduced to us through his ability to care for horses, suggesting an intimacy with the living animal world. At the intersection of love and labor, Bushrod’s affection meets the violent language of “breaking a horse” for human use. In the early decades of this new century, the ability to make a living through that work is drying up.

While Bushrod’s future may be unclear, Thomasine’s past is purposefully obscure. Early on, she tells a white woman that she is “from a lot of places,” before going on to signify that “my folks helped build [this town]. […] I didn’t have no mama and daddy.” At the foundation of Bushrod’s life is his labor and love for horses; at the basis of Thomasine’s is opacity. She knows how to dissemble and disguise herself. Acquaintances may not know her but, as a successful bounty hunter, Thomasine makes sure to know everyone. After all, her job depends on it. To get along, she seeks out and delivers to the state those who have prices on their head.

It is in this polarity, where one who cares for life and another who aids its subjugation, that the two complement each other. The film is animated by staging their meeting: when Thomasine sees that there is a bounty on Bushrod, she searches him out. Together the two, rekindle a past relationship, one that existed prior to the start of the film. But what might a community look like between one who avoids the state and another who, at least for a time, chooses to act on behalf of it? Where does love founder as one falls into it?

Love provides a fulcrum of support that nothing else can. About two-thirds of the way through Thomasine and Bushrod, our two leads escape into the mountainside where they meet Indigenous peoples hiding from settlers. The group recounts Bushrod’s origins as a member of the Comanche nation. It is a brief scene, one which attempts to demonstrate a connection between the genocide of Native peoples and the persistent anti-Black violence of the country. This moment also draws our attention to how Thomasine and Bushrod’s love is visible to those attuned to recognize it. One woman, Pecolia, acknowledges that intimacy, and in a moment of concern, offers the advice that both fugitives need to “be careful of your brother.” In this same conversation, Bushrod calls Thomasine his wife, a surprising note predicated less on any legalistic definition than some sort of metaphysical shared romantic bond.

Following this exchange, Thomasine and Bushrod take refuge in a building. Bushrod cleans guns as Thomasine, a bottle of wine in hand, adorns the wall with their wanted poster. The poster is a sign of infamy, a document as legitimating as any marriage license. Bushrod declares his love and adoration, but something has happened. Thomasine raises Bushrod’s prior claim of marriage, as though a secret has been let out: “You told that blind woman I was your wife.” A past truth has found itself in the present; by describing Thomasine as his wife, Bushrod reciprocates a gesture from earlier in the film. The first time we see Bushrod and Thomasine together onscreen is in Bushrod’s rented bedroom. He is surprised to see her: Thomasine only gained access to the room by telling the innkeeper that she is Bushrod’s wife. Now, Bushrod’s affectionate mention of marriage takes Thomasine off-guard, so she swiftly moves forward, riffing on the advice from Pecolia. “If you can’t trust your brother, then you can’t trust nobody,” she tells him. The connection is there, tethered not only to romance but to trust between two people. Bushrod retorts, “And if you can’t trust nobody, there ain’t no sense in a word called trust.” Whatever the two said to anyone else, they need to express their love to each other.

In a moment of dwelling, it is clear that the two have built a world. By trusting one another, the two are able to reject external categorizations that simplify and reduce. The hammering of the wanted sign to the wall, the cleaning of the gun, the drinking of the wine: these all bring together the two as they find some soft, quiet connection while on the run. These are the ordinary gestures of care shared in a world set on extinguishing Black life. Thomasine and Bushrod may be aligned sartorially, donning the most fabulous outfits of purple blouses, effervescent chaps, and powder blue dresses as bank robbers.

They must share something greater. By examining the meaning of the word trust, they understand one another.

What is so striking about this scene is how it immediately follows a sequence in which Thomasine and Bushrod become intimately familiar with the relationship between media, language, and truth. The two are not only fugitives, but they are aware of the ways that the outside world impinges on them. They understand the process of categorization and mischaracterization. Earlier in the film, when the two get their picture taken, Thomasine knows that their photo will appear in the papers. She makes a point to stand to Bushrod’s right, so that she will appear on the left side in the photo and that newspapers will describe the two as “Thomasine and Bushrod,” rather than “Bushrod and Thomasine.” Her name comes first: syntax matters, and equally, so does a shared semantic galaxy. In a world of classifications, the two must find an adequate language to express tenderness. To abandon everything, to refuse the edifice of language, would create an impossibility — one couldn’t express trust and consequently, well, “there ain’t no sense in a word called trust.” Their words and their world would lose its meaning.

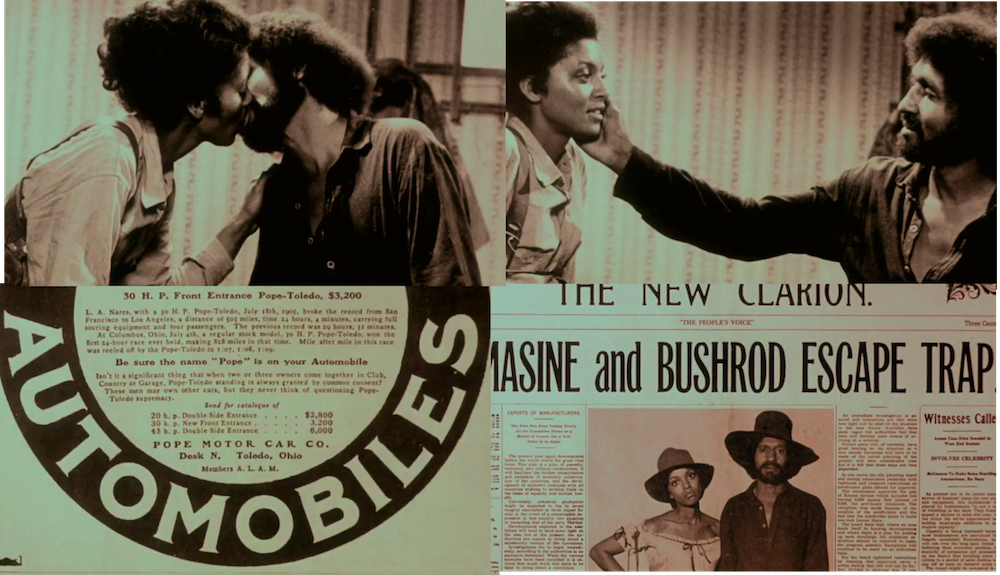

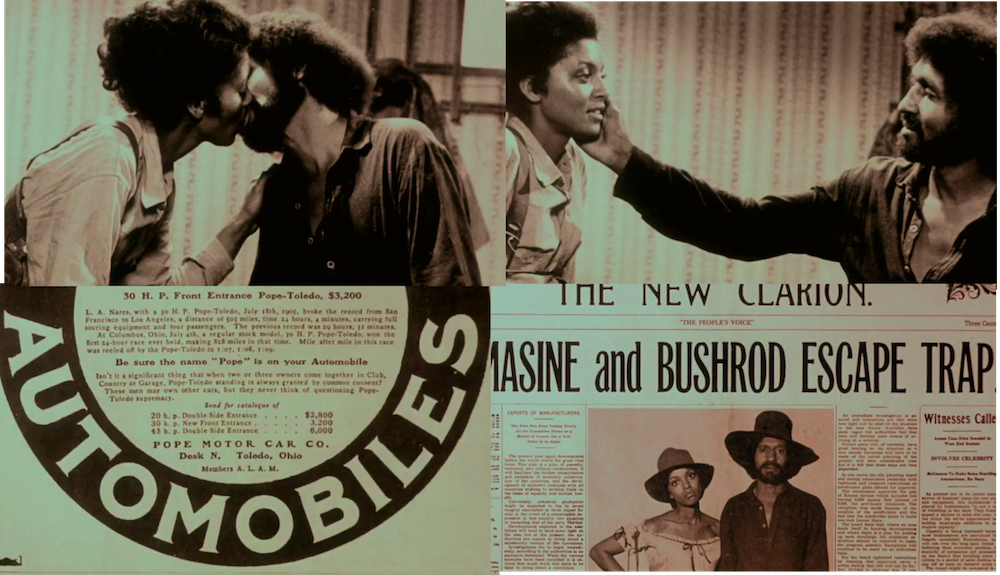

That awareness of external classification recurs when the two become folk legends, known for redistributing money seized from banks to poor whites, Blacks, and Native people. In the middle of the film, two montages chart their journey to togetherness. Composed primarily of sepia images of the two spliced with pictures of the marshal searching them out, these collages are also interspersed with brief scenes of Thomasine and Bushrod in colorful attire as they rob banks. Reward posters are shown with the bounty going higher, revealing their growing fame and the state’s desire to capture the two “Dead or Alive.” There are also unidentified images of Black children and adults, wagon wheels, religious figures, advertisements for cars and telephones, a diptych of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln, and, perhaps most startling, shots of quiet moments between lovers.

We see Bushrod’s hand on Thomasine’s face, followed by a still of the two kissing. Here is a historical reality that never was. We are granted both intimacy and wider context; their world and the world.

Between the two montages, Thomasine and Bushrod take refuge in a broken-down church. There they read the paper. The stories, as one might expect, are littered with lies. Perhaps most viciously, Thomasine and Bushrod’s relationship is turned inside out and made to seem violent, with one article claiming, as Thomasine reads aloud, “She again tried to force him […] only this time, he viciously slapped her in the face.” We’ve seen their escapades. We trust the vision of the film has been real; it is clear that the papers falsify. “They’re really trying to get us, aren’t they?” Bushrod asks, before Thomasine replies: “At least that picture [of us is] a little clearer. You know, that last one was so dark, you couldn’t even see us.” But what is there to see? Bushrod/Julien, the character and the actor-writer, slowly surveys the off-screen space in front of him. His eyes don’t dart around. He isn’t frantic. Here is a performance of contemplation, a recognition of the fiction of this reporting. We’re not a part of that miscreation — we’ve seen their love through the improvisational actions of two partners eager to find a footing in a world.

These images of trust and love and the film’s montage, reveal not only what Saidiya Hartman might call the wayward lives of supposed minor figures, but also how those lives refuse so many categorizations. Thomasine and Bushrod’s relationship can’t be captured; the intimacy between the two can’t be apprehended. That care exists between those who, as we learn, were a couple before and have now, after separating, come together again. We can and should only (lest we be voyeurs with an imperialist zeal to swipe another’s experience) catch glimpses. Images flicker quickly, moving between one another multiple times within a second. With these montages, we glean something approaching that is collective, unique, and unable to be subsumed from the outside. Thomasine and Bushrod’s life won’t be classified or known to those outside of it: it can only be gestured to. As powerful as these montages are, they also stage the failure of comparative logics that might seek to see our two leads as a kind of Bonnie and Clyde. That ascription comes from without and has little care for the details of Black life.

So, why has the “Black Bonnie and Clyde” moniker remained? The comparison serves as an easy shorthand reflecting a couple of shared ingredients. Like Penn’s film, Thomasine and Bushrod follows two fugitives who love each other, become folk heroes, and whose filmic fate is wrapped in a fatal finale. Bonnie and Clyde’s success became legendary itself; if its reception was at first controversial, it is a violent representation of youthful love on the run, emerging at the dissolution of the Classical studios marked, as Roger Ebert wrote, “a milestone in the history of American movies, a work of truth and brilliance.” There is that word again: truth. When Bonnie and Clyde premiered in 1967, no Black artist had helmed a major studio picture as a director. And while Thomasine and Bushrod was financially successful, it was still subjected to the peculiar racist critiques of the time. In New York magazine, Judith Crist barely reviewed the film, opting instead to ask, after a few dismissive words, “Why beat a dog that is dead for a willing viewer and shows only a post-mortem twitch or two for a specialized one?” Genre caters to “specialized” audiences. For Crist, a Black audience that mattered was illusory. Here is the problem of the comparison, made clear by so many Blaxploitation films that provoke, preside, and bypass our common-sense expectations. Genre is not something to be discarded, but its abstractness, when explicitly complicated by race, creates an unstable categorization that becomes almost, but not quite, whole by necessarily having holes.

Films with Black casts have always been ripe for oversimplified designations by viewers who, all too often unfamiliar with any lineage, didn’t feel there was much to know until they were shocked by some widely publicized contemporary event, rebellion, or call for justice. This happened in 2015 following April Reign’s hashtag #OscarsSoWhite, which drew attention to the Academy’s failure to recognize work by Black artists and people of color. Over the last year, the public representation of state violence, which so many knew of and so many seemed to purposefully avoid, took shape in the response from corporations which proclaimed that Black Lives Matter. In some sense, the call from streaming services that “Black Films Matter” suggests something approaching the beginnings of redress. What redress looks like isn’t so apparent. After all, ambiguous characterizations like genre can serve advertisers and the industry more than anyone else — one need only look at the way that Judas and the Black Messiah capitalized on the life of a Black radical thinker and revolutionary activist to squeeze out something not too different from the typical biopic’s project. Audiences interested less in authentic stories than imaginative freedom dreams and surrealist excursions have been let down by critical comparisons to supposed white forerunners. What I mean to say is that the description of something like Thomasine and Bushrod as a Black Bonnie and Clyde foments an untrustworthy expectation and desire with a thin imagination. The comparison not only anchors itself in the success of a more widely acknowledged “white film,” but it coerces a similarity that doesn’t seem to be there. Further, the juxtaposition imagines an audience for Thomasine and Bushrod that can’t exist because the film isn’t what is promised — the racist logic fails even in its descriptive claims. To call the film a Black (as in its characters are Black) Western (as in it features sheriffs, horses, and desert landscapes where the genocide of Native people is vaguely visible) is to point out that the Western exists in a history sculpted by white supremacy. The label doesn’t go further. It draws attention without unveiling the complexities of that production.

To say that something matters is to say we should pay attention, care for, uplift, criticize, celebrate, interpret, and reckon with. Critics may be tempted to read Thomasine and Bushrod as some bridge to the cinephile’s pantheon: that place where recognition of Gordon Parks Jr.’s artistry would situate him alongside those celebrated New Hollywood visionaries Francis Ford Coppola, Arthur Penn, and Brian De Palma. To slot one alongside another is to partake in that same project of framing Thomasine and Bushrod as a Black Bonnie and Clyde. If the goal is to make one work legible for immediate consumption, there you have it: simplification abounds and the sharp edges of art, where audiences are in a constant negotiation of identifying and disidentifying, are lost. For Max Julien, the film represented a way to continue “mak[ing…] movies according to the occult.” Thomasine and Bushrod was one entry in a changing landscape where, as Julien noted, “I sat and cried for white people. Now white people can cry for the Black people.” Perhaps in that crying is a hope for trust and understanding. Then again, no single film can redistribute and reinstate trust the way that Thomasine and Bushrod could give money away.

Nicholas Forster is a writer and lecturer in African American Studies and Film & Media Studies at Yale University. He publishes a newsletter on acting and film called Looking at the Floor and is currently writing a biography of Bill Gunn.

In the wake of this past summer and the police killing of George Floyd, film companies and streaming services mobilized the rhetoric of “Black Lives Matter” for proprietary possibilities to insist on something like “Black Movies Matter.” These calls sought to create confidence that there was some corporate accountability and awareness of what was going on in the country. Even as this is a corrective to racist canonical histories, what remains unclear here is what it means to matter: how might such a claim relate to the omnipresence of anti-Black violence, which resides at the foundation of the modern world? Do these films matter in the sense that they are of aesthetic importance or political significance? If so, how does a cycle of production like Blaxploitation (1970–1976), in which Black artists often starred in films produced for the gains of white investors, promote a mattering that, well, matters? While there is a connection between these calls and the recent deluge of anti-racist reading lists, the streaming services’ categorizations are a bit different, a bit more nuanced, less driven by the moment and more historically oriented. Nevertheless, watching a movie might change your life, but watching a film from the 1970s won’t save another’s.

In the late ’70s, amid the rise and fall of Blaxploitation, scholar Thomas Cripps sought to mark out what it would mean for Black film to be a genre. Film studies as a discipline was still in its infancy, and semiotics, ideological critique, and psychoanalysis provided popular methodologies to adjudicate and interpret movies. Bringing these together, Cripps’s gambit was to suggest that Black film “ritualizes the myth of winning” by “celebrat[ing] aesthetique du cool,” whereas Blaxploitation films merely turned to “sneering and bravado.” Designating Black film as a genre, Cripps registered the significance of ritual viewing experiences that contained a set of internal codes and alternative scripts hailing different audiences. Comparing Black film to “black magazine[s] that [print] soul food recipes, or the black student newspaper[s] […] featur[ing] a glossary of black argot,” Cripps claimed that Black films represented the “uses and beauties” of “black identity.” Here, genre brought with it a faith in the beauty of Black life.

Still, Cripps played into a game of legitimation and meaning. Where the category “Black film” offered a mythic landscape of “soul,” Blaxploitation, with its supposed financially motivated digestibility, was about “shrill imitation.” To imitate, for Cripps, is to be inauthentic, untrustworthy. Over the last year, a similar set of evaluative moves have emerged as the film industry comes to terms with its own sense of hierarchies regarding Black art. Streaming services proclaim a recognition of Black film worlds while (particularly white) critics, seemingly eager to right the wrongs of the past, jump in to champion work by Black filmmakers. Of course, an identity is not the same as a positionality, nor do shared identities necessitate shared aesthetic or political investments. While debates about what constitutes “Black Art” have been complicated and importantly waged over the last century, the recent turn backward, to a history of “Black Films” that matter, marks a difficult renegotiation over how characterization can limit even as it seeks to expand.

Gordon Parks Jr.’s 1974 film Thomasine and Bushrod allegorizes the tangled knot of genre, race, and film by suggesting that media characterization and its attempts to classify can’t quite acknowledge the intricacy of Black life. While the film has been available online for some time, Thomasine and Bushrod was recently added to the Criterion Channel and was inserted into the prestige service’s “Black Westerns” collection. This collection revises Thomasine and Bushrod’s original reception, ever so slightly. It was first released two years after Parks’s smash hit Superfly, and critics have often framed it as a Blaxploitation film. Now, it bears the weight of a different, albeit still problematic, classification of “Black Western.”

Set in Texas at the spatial frontier of a nation in the early 1910s (prior to New Mexico and Arizona being colonially annexed into the United States), where the supposed emergence of the twin marvels of the automobile and the train marked ongoing industrialized modernization, the generic description promises some descriptive coherency. Alongside this classification is a thornier language of comparison: critics, industry mags, and advertisers have framed Thomasine and Bushrod as a Black version of some white film. In 1974, the critic Tom Stokes called the movie “a darker Butch Cassidy,” a sense of shading animated less by any shared themes than by the visibility of race. In 2021, Criterion described Thomasine and Bushrod as “Blaxploitation’s answer to Bonnie and Clyde.”

But what is the question, posed by Arthur Penn’s film, that Thomasine and Bushrod answers? Both of these descriptors rely less on the stuff of the film and more on the logics of comparison, which act as shortcuts to draw a relationship, without probing the significance or the specifics of how Parks’s film complicates any generic delimitation. Those descriptions fail as much now as they did nearly half a century ago.

Thomasine and Bushrod is as much about the travails of remarriage and the ragged ways people express love as it is about the mythic space of “the West.” Rather than reinforce these classifications, it feels more adequate, whatever that might entail, to engage on the terms that Max Julien (the writer and lead actor), Gordon Parks Jr. (the director), and Vonetta McGee (the co-lead and Julien’s partner at the time) offer. Bushrod, played by Julien, is a lover — of life, of fugitivity, of the world around him. He is introduced to us through his ability to care for horses, suggesting an intimacy with the living animal world. At the intersection of love and labor, Bushrod’s affection meets the violent language of “breaking a horse” for human use. In the early decades of this new century, the ability to make a living through that work is drying up.

While Bushrod’s future may be unclear, Thomasine’s past is purposefully obscure. Early on, she tells a white woman that she is “from a lot of places,” before going on to signify that “my folks helped build [this town]. […] I didn’t have no mama and daddy.” At the foundation of Bushrod’s life is his labor and love for horses; at the basis of Thomasine’s is opacity. She knows how to dissemble and disguise herself. Acquaintances may not know her but, as a successful bounty hunter, Thomasine makes sure to know everyone. After all, her job depends on it. To get along, she seeks out and delivers to the state those who have prices on their head.

It is in this polarity, where one who cares for life and another who aids its subjugation, that the two complement each other. The film is animated by staging their meeting: when Thomasine sees that there is a bounty on Bushrod, she searches him out. Together the two, rekindle a past relationship, one that existed prior to the start of the film. But what might a community look like between one who avoids the state and another who, at least for a time, chooses to act on behalf of it? Where does love founder as one falls into it?

Love provides a fulcrum of support that nothing else can. About two-thirds of the way through Thomasine and Bushrod, our two leads escape into the mountainside where they meet Indigenous peoples hiding from settlers. The group recounts Bushrod’s origins as a member of the Comanche nation. It is a brief scene, one which attempts to demonstrate a connection between the genocide of Native peoples and the persistent anti-Black violence of the country. This moment also draws our attention to how Thomasine and Bushrod’s love is visible to those attuned to recognize it. One woman, Pecolia, acknowledges that intimacy, and in a moment of concern, offers the advice that both fugitives need to “be careful of your brother.” In this same conversation, Bushrod calls Thomasine his wife, a surprising note predicated less on any legalistic definition than some sort of metaphysical shared romantic bond.

Following this exchange, Thomasine and Bushrod take refuge in a building. Bushrod cleans guns as Thomasine, a bottle of wine in hand, adorns the wall with their wanted poster. The poster is a sign of infamy, a document as legitimating as any marriage license. Bushrod declares his love and adoration, but something has happened. Thomasine raises Bushrod’s prior claim of marriage, as though a secret has been let out: “You told that blind woman I was your wife.” A past truth has found itself in the present; by describing Thomasine as his wife, Bushrod reciprocates a gesture from earlier in the film. The first time we see Bushrod and Thomasine together onscreen is in Bushrod’s rented bedroom. He is surprised to see her: Thomasine only gained access to the room by telling the innkeeper that she is Bushrod’s wife. Now, Bushrod’s affectionate mention of marriage takes Thomasine off-guard, so she swiftly moves forward, riffing on the advice from Pecolia. “If you can’t trust your brother, then you can’t trust nobody,” she tells him. The connection is there, tethered not only to romance but to trust between two people. Bushrod retorts, “And if you can’t trust nobody, there ain’t no sense in a word called trust.” Whatever the two said to anyone else, they need to express their love to each other.

In a moment of dwelling, it is clear that the two have built a world. By trusting one another, the two are able to reject external categorizations that simplify and reduce. The hammering of the wanted sign to the wall, the cleaning of the gun, the drinking of the wine: these all bring together the two as they find some soft, quiet connection while on the run. These are the ordinary gestures of care shared in a world set on extinguishing Black life. Thomasine and Bushrod may be aligned sartorially, donning the most fabulous outfits of purple blouses, effervescent chaps, and powder blue dresses as bank robbers.

They must share something greater. By examining the meaning of the word trust, they understand one another.

What is so striking about this scene is how it immediately follows a sequence in which Thomasine and Bushrod become intimately familiar with the relationship between media, language, and truth. The two are not only fugitives, but they are aware of the ways that the outside world impinges on them. They understand the process of categorization and mischaracterization. Earlier in the film, when the two get their picture taken, Thomasine knows that their photo will appear in the papers. She makes a point to stand to Bushrod’s right, so that she will appear on the left side in the photo and that newspapers will describe the two as “Thomasine and Bushrod,” rather than “Bushrod and Thomasine.” Her name comes first: syntax matters, and equally, so does a shared semantic galaxy. In a world of classifications, the two must find an adequate language to express tenderness. To abandon everything, to refuse the edifice of language, would create an impossibility — one couldn’t express trust and consequently, well, “there ain’t no sense in a word called trust.” Their words and their world would lose its meaning.

That awareness of external classification recurs when the two become folk legends, known for redistributing money seized from banks to poor whites, Blacks, and Native people. In the middle of the film, two montages chart their journey to togetherness. Composed primarily of sepia images of the two spliced with pictures of the marshal searching them out, these collages are also interspersed with brief scenes of Thomasine and Bushrod in colorful attire as they rob banks. Reward posters are shown with the bounty going higher, revealing their growing fame and the state’s desire to capture the two “Dead or Alive.” There are also unidentified images of Black children and adults, wagon wheels, religious figures, advertisements for cars and telephones, a diptych of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln, and, perhaps most startling, shots of quiet moments between lovers.

We see Bushrod’s hand on Thomasine’s face, followed by a still of the two kissing. Here is a historical reality that never was. We are granted both intimacy and wider context; their world and the world.

Between the two montages, Thomasine and Bushrod take refuge in a broken-down church. There they read the paper. The stories, as one might expect, are littered with lies. Perhaps most viciously, Thomasine and Bushrod’s relationship is turned inside out and made to seem violent, with one article claiming, as Thomasine reads aloud, “She again tried to force him […] only this time, he viciously slapped her in the face.” We’ve seen their escapades. We trust the vision of the film has been real; it is clear that the papers falsify. “They’re really trying to get us, aren’t they?” Bushrod asks, before Thomasine replies: “At least that picture [of us is] a little clearer. You know, that last one was so dark, you couldn’t even see us.” But what is there to see? Bushrod/Julien, the character and the actor-writer, slowly surveys the off-screen space in front of him. His eyes don’t dart around. He isn’t frantic. Here is a performance of contemplation, a recognition of the fiction of this reporting. We’re not a part of that miscreation — we’ve seen their love through the improvisational actions of two partners eager to find a footing in a world.

These images of trust and love and the film’s montage, reveal not only what Saidiya Hartman might call the wayward lives of supposed minor figures, but also how those lives refuse so many categorizations. Thomasine and Bushrod’s relationship can’t be captured; the intimacy between the two can’t be apprehended. That care exists between those who, as we learn, were a couple before and have now, after separating, come together again. We can and should only (lest we be voyeurs with an imperialist zeal to swipe another’s experience) catch glimpses. Images flicker quickly, moving between one another multiple times within a second. With these montages, we glean something approaching that is collective, unique, and unable to be subsumed from the outside. Thomasine and Bushrod’s life won’t be classified or known to those outside of it: it can only be gestured to. As powerful as these montages are, they also stage the failure of comparative logics that might seek to see our two leads as a kind of Bonnie and Clyde. That ascription comes from without and has little care for the details of Black life.

So, why has the “Black Bonnie and Clyde” moniker remained? The comparison serves as an easy shorthand reflecting a couple of shared ingredients. Like Penn’s film, Thomasine and Bushrod follows two fugitives who love each other, become folk heroes, and whose filmic fate is wrapped in a fatal finale. Bonnie and Clyde’s success became legendary itself; if its reception was at first controversial, it is a violent representation of youthful love on the run, emerging at the dissolution of the Classical studios marked, as Roger Ebert wrote, “a milestone in the history of American movies, a work of truth and brilliance.” There is that word again: truth. When Bonnie and Clyde premiered in 1967, no Black artist had helmed a major studio picture as a director. And while Thomasine and Bushrod was financially successful, it was still subjected to the peculiar racist critiques of the time. In New York magazine, Judith Crist barely reviewed the film, opting instead to ask, after a few dismissive words, “Why beat a dog that is dead for a willing viewer and shows only a post-mortem twitch or two for a specialized one?” Genre caters to “specialized” audiences. For Crist, a Black audience that mattered was illusory. Here is the problem of the comparison, made clear by so many Blaxploitation films that provoke, preside, and bypass our common-sense expectations. Genre is not something to be discarded, but its abstractness, when explicitly complicated by race, creates an unstable categorization that becomes almost, but not quite, whole by necessarily having holes.

Films with Black casts have always been ripe for oversimplified designations by viewers who, all too often unfamiliar with any lineage, didn’t feel there was much to know until they were shocked by some widely publicized contemporary event, rebellion, or call for justice. This happened in 2015 following April Reign’s hashtag #OscarsSoWhite, which drew attention to the Academy’s failure to recognize work by Black artists and people of color. Over the last year, the public representation of state violence, which so many knew of and so many seemed to purposefully avoid, took shape in the response from corporations which proclaimed that Black Lives Matter. In some sense, the call from streaming services that “Black Films Matter” suggests something approaching the beginnings of redress. What redress looks like isn’t so apparent. After all, ambiguous characterizations like genre can serve advertisers and the industry more than anyone else — one need only look at the way that Judas and the Black Messiah capitalized on the life of a Black radical thinker and revolutionary activist to squeeze out something not too different from the typical biopic’s project. Audiences interested less in authentic stories than imaginative freedom dreams and surrealist excursions have been let down by critical comparisons to supposed white forerunners. What I mean to say is that the description of something like Thomasine and Bushrod as a Black Bonnie and Clyde foments an untrustworthy expectation and desire with a thin imagination. The comparison not only anchors itself in the success of a more widely acknowledged “white film,” but it coerces a similarity that doesn’t seem to be there. Further, the juxtaposition imagines an audience for Thomasine and Bushrod that can’t exist because the film isn’t what is promised — the racist logic fails even in its descriptive claims. To call the film a Black (as in its characters are Black) Western (as in it features sheriffs, horses, and desert landscapes where the genocide of Native people is vaguely visible) is to point out that the Western exists in a history sculpted by white supremacy. The label doesn’t go further. It draws attention without unveiling the complexities of that production.

To say that something matters is to say we should pay attention, care for, uplift, criticize, celebrate, interpret, and reckon with. Critics may be tempted to read Thomasine and Bushrod as some bridge to the cinephile’s pantheon: that place where recognition of Gordon Parks Jr.’s artistry would situate him alongside those celebrated New Hollywood visionaries Francis Ford Coppola, Arthur Penn, and Brian De Palma. To slot one alongside another is to partake in that same project of framing Thomasine and Bushrod as a Black Bonnie and Clyde. If the goal is to make one work legible for immediate consumption, there you have it: simplification abounds and the sharp edges of art, where audiences are in a constant negotiation of identifying and disidentifying, are lost. For Max Julien, the film represented a way to continue “mak[ing…] movies according to the occult.” Thomasine and Bushrod was one entry in a changing landscape where, as Julien noted, “I sat and cried for white people. Now white people can cry for the Black people.” Perhaps in that crying is a hope for trust and understanding. Then again, no single film can redistribute and reinstate trust the way that Thomasine and Bushrod could give money away.

¤

Nicholas Forster is a writer and lecturer in African American Studies and Film & Media Studies at Yale University. He publishes a newsletter on acting and film called Looking at the Floor and is currently writing a biography of Bill Gunn.

LARB Contributor

Nicholas Forster is a writer and lecturer in African American Studies and Film & Media Studies at Yale University. He publishes a newsletter on acting and film called Looking at the Floor and is currently writing a biography of Bill Gunn.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Do Black Lives Matter to Westworld? On TV Fantasies of Racial Violence

Hope Wabuke considers the violence against black children at the heart of HBO's Westworld and whether the show will ever have something to say about...

The Double Bill as Dialogue: On Eileen Myles’s “The Trip” and Ivan Dixon’s “The Spook Who Sat by the Door”

Elizabeth Horkley delves into the filmmaking and curatorial work of Eileen Myles, most recently in their double bill program at the Metrograph...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!