THIS PIECE APPEARS IN THE HIGH/LOW ISSUE OF THE LARB QUARTERLY JOURNAL, NO.29.

¤

1/

THE MOVEMENT FOR BLACK LIVES has grown during the pandemic. Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter are shaping so many people’s sense of racial justice. The problem is, social media is a technology of the white gaze. It feeds off of racial violence; killings go viral. Hooked to our phones, we circulate and cycle through Black death.

We need more life. Asian Americans in particular need strategies for demanding recognition beyond the schema of racial violence — especially so our visibility does not form at the expense of Black people.

In this essay, I turn the gaze onto non-Black people who make a show of looking at Black death. I close read the viral discourse compiled by #AhmaudArbery. I examine social media virality itself and surface the contradictions that organize discourse about racial justice.

This essay makes space to ask: What are just and genuine ways of being Asian American beyond white adjacency and Black alignment? What are ways of doing Asian American that would make “for Black lives” redundant?

That’s it. That’s the whole argument.

Scroll on.

Today is May 5. I’m stretching before a run, listening to a podcast. The hosts, who live in New York, refer to the city as the epicenter of the coronavirus.

The diction strikes me: a term for earthquakes used to describe a disease whose spread exceeds any center. The metaphor of the more familiar disaster gives shape to an otherwise uncontainable pandemic. In form we find safety even when it comes to harm.

One of my former high school students posts an IG story. It’s about a case of “jogging while Black.” It lists action steps for holding the killers accountable. Here’s my Woke Asian response.

At first I'm confused. I came across similar news two months ago, at the start of shelter-in-place, but that case wasn't viral then. Is this a different murder? Did another Black man get killed while out on a run?

I can guess who posted about that killing: the Woke Hapa. I met him years ago, at a conference for ethnic studies teachers. I remember my discomfort at hearing a visibly Asian man speak with the cadence of spoken word, which to my ears at least takes on the sounds of Blackness. I can imagine him calling people “fam” and greeting people with “what’s good?”

I go to his Facebook and scroll through his feed. I look and I look for that first post. Was it the same man?

I give up. I can’t find it. The Woke Hapa posts a lot.

I go back to IG. I Google the name of the man in my student’s post: Ahmaud Arbery. Killed on February 23.

The timeline makes sense. It’s the same man. It’s Ahmaud again.

In Playing in the Dark, Toni Morrison examines what she calls American Africanism: how white US writers imagine Black people in the pages of literary fiction. As Morrison argues, literary scholars have failed to pay attention to the mechanisms of race in canonical US fiction even (or especially) when race is operative. By revisiting Willa Cather, Ernest Hemingway, and other canonized authors, Morrison makes the case that white writers have used Black figures to make sense of what it means to be American. She calls this scheme the literary imagination.

What’s the difference between the gaze and the imagination? The white gaze is a relational concept. It assumes a subject and an object. The subject looks, the object is looked upon. The imagination requires no object. One can imagine the Other entirely alone. As Morrison did in 1992 and writers of color today continue to point out, white writers fail at imagining characters of color when they lack substantive relationships with actual people of color. Nonetheless, just because the imagination is private does not make it any less deadly, a point Claudia Rankine made viral. IYKYK.

Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination is about how white writers imagined Black people during de jure segregation. Morrison’s work is groundbreaking, yet the white gaze is something else.

2/

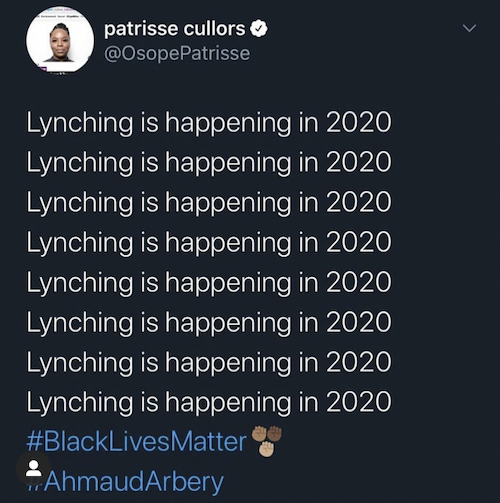

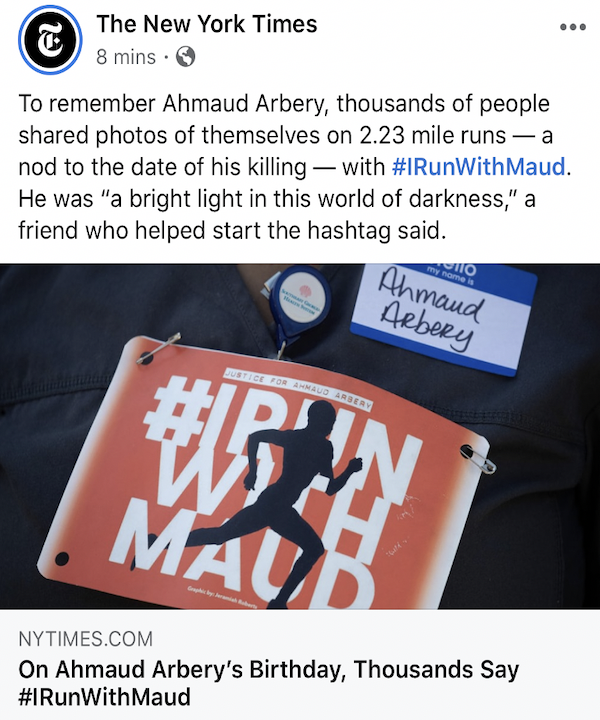

May 7. It’s viral now.

There’s a lag time between an incident going viral on social media and that same incident scaling up into digital news media. As of 6:00 p.m. Pacific, the landing page of The New York Times has no mention of Arbery’s killing even though Patrisse Cullors’s tweet is every fourth post in my social media feeds. The delay throws me for a loop.

Eventually, the Times catches up, posting their reporting on social media. These delayed posts are like aftershocks.

The language of earthquakes. One emergency as heuristic for another.

The next day, May 8. Morning.

Awareness of Arbery’s murder has grown exponentially again. Most of the people posting about it are not Black. Not a few of them are white.

I can’t help but think that all this posting is not about raising awareness. Our social media feeds are echo chambers. It’s a well-known problem. By the time you find out about something, your followers probably have as well. So, if any cause is really at stake today, it’s people’s status as anti-racist.

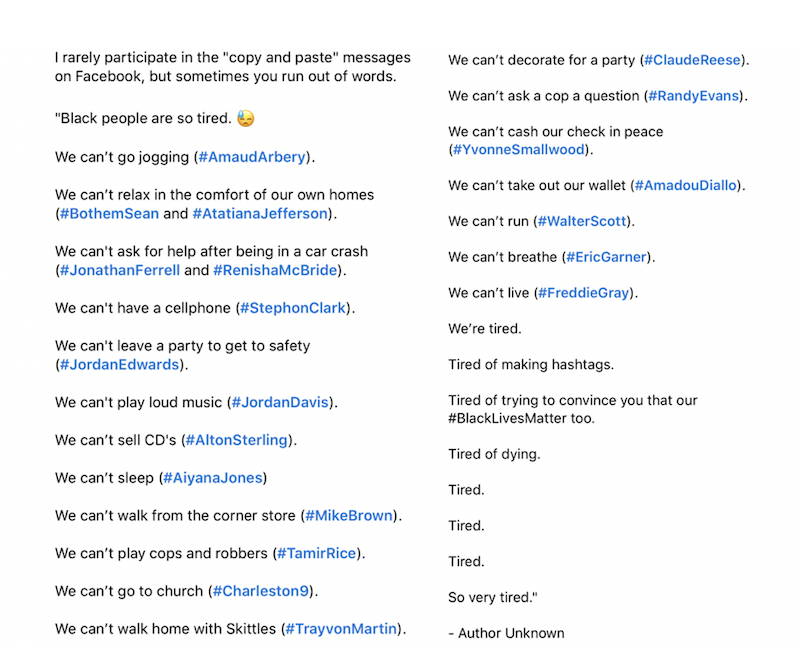

Another post is going around. Here’s the start and end of it.

Even a non-Black person posts this, editing all the "we" pronouns to "they."

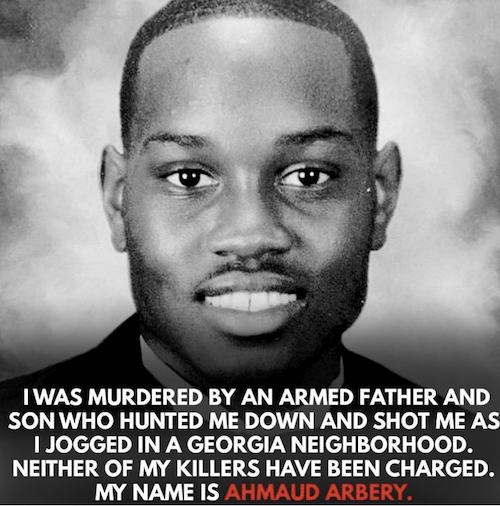

This — two white men killing a young Black man while he was doing something harmless and recreational — running — this is violence that’s legible and indisputable.

Amid all this, I get an ad for a Times virtual event. It’s about running. I click on it to check whether anyone has commented on the terrible timing.

Guess.

During the pandemic, I have looked for other ways to describe the phenomenon of “going viral.” The metaphor seems insensitive now. But in the case of #AhmaudArbery, we would lose something not to examine the coincidence.

The paradox of social media virality is this: people spread content that’s already repeating on their feed. This choice runs counter to traditional publication, where the norm is novelty. In turn, the expectation is to cater to the unknowing. Take, for instance, the most obvious tell of the white gaze: the explanatory comma.

The social media acronym “IYKYK” upends the value placed on the unknown. It is the slightest status symbol, rewarding those who already know. Thus, IYKYK exposes novelty as a matter of the gaze. Novel to whom? The whole premise of writing something new is a norm that steers people away from writing for their own communities. It disciplines people into writing for the white gaze.

All these Arbery posts today are the equivalent of IKYKNYKIK: I know you know, now you know I know.

If the topic were anything with lower stakes (e.g., exchanging a glance with the other person of color during a particularly white writing workshop), such rhetorical games might be fun, even useful. But the topic is not innocuous. It is the vulnerability of Black people to state-sanctioned violence and premature death.

Anti-Blackness is the most enduring US currency. These days, social media traffics in virtue signaling. In other words, the economy commodifies Black pain, and non-Black people profit. We make a killing.

“I know you know, now you know I know” comes at a cost to the people who have to know, who’ve been knowing, whose overdetermined knowability to the white gaze is the very problem.

The cost, I think, is Black people’s dignity. The knowledge that liberals like me go out of my way to buy the Ta-Nehisi Coates–edited issue of Vanity Fair with a Breonna Taylor portrait on the cover while the state consistently values real estate over Black life — that people invest more to mourn Black people than to protect Black people — that a Black person murdered moves this country more than a Black person creating excelling coping struggling defying — the knowledge of what this nation values and whom it denies life — it must eat at Black people’s dignity.

Ours is a country that acknowledges Black people most upon their murder. White liberals would call such decency love, but no. It is a sickness when Black death is clickbait.

White consumption powers our timelines. It insists on knowing where things stand to maintain order and control. Social media enforces a legibility — a cleanness, a purity — that secures the arrangements of white supremacy. Consequently, obedience and fear govern social justice culture online and off. What I’m saying is: cancel culture, generally blamed on the POC left, might be more deeply understood as an extension of the white gaze.

I hope that people read and share this essay. I fear getting cancelled. I want to get out.

Morrison did talk about the white gaze. Her pithy example regards Invisible Man. She brings it up in conversation with Junot Díaz.

“Invisible to whom?” she says. “Not me, so that’s already a wonderful book that still has that other gaze.”

People post her Charlie Rose interview more, the excerpt with this couched and encoded question: “Bill Moyers, I think, once asked you the question: can you imagine writing a novel that’s not centered about race?”

“Yes, I can write about white people,” she says. (Leave it to a white man to appeal to white male authority to hide white supremacy.) “White people can write about Black people. Anything can happen in art. There are no boundaries there.”

This is 1998. She’s won the Pulitzer and the Nobel. Perhaps that informs the matter-of-factness with which she pronounces these permissions. This is no longer the party line for writers of color in 2020. Because of the violence of the white literary imagination, we are often called upon to enforce the lanes.

Morrison credits African writers such as Chinua Achebe and diasporic writers like Aimé Césaire, “who could assume the centrality of their race.” In their work,

[T]here were the parameters. I could step in now, and I didn’t have to be consumed by or be concerned by the white gaze. […] It has nothing to do with who reads the books. Everyone of any race, any gender, any country. But my sovereignty and my authority as a racialized person had to be struck immediately with the very first book.

So what is the gaze if “it has nothing to do with who reads the books”? Every decision a text makes implies the gaze that it centers, which is to say, the experiences, values, and worldviews that it validates. Instead of “Who is the audience for this?”, we can ask “Who are its people?”, even “What communities does it serve?”

When people of color decenter the white gaze, we are, as Morrison says, claiming our sovereignty. In contrast, writing for the white gaze is upholding this nation's founding principle: that white lives matter at everyone’s expense.

3/

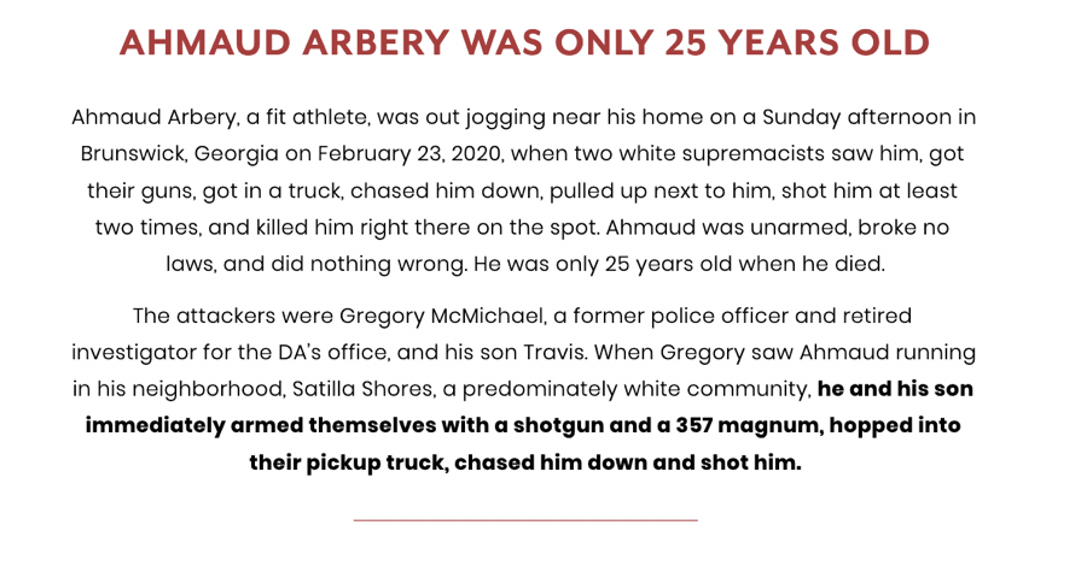

Overnight, an infrastructure has cropped up to organize around the injustice. On May 8, this is the centerpiece of runwithmaud.com:

I don’t sign the site’s petition.

It’s a revealing choice to characterize Arbery so minimally: “a fit athlete,” “unarmed,” “only 25 years old when he died.” If I were writing a Black male character, my first move would not be to describe his physicality. It would be a shortcoming of the imagination to characterize a Black man as athletic, valued for physical labor. That’s to say the least.

Whereas this narrative presents Arbery as a trope, stripped of dignity, the two killers get backstory and social context. If these paragraphs showed up in a writing workshop, I would think the story was about the two white men. Notice, for instance, how the text stretches out the act of violence into so many extraneous steps. This story plays out like an action flick, its protagonist not Ahmaud.

The text not only slows down the violence. It repeats the scene and bolds it for emphasis.

What Black audience would want this nightmare played on loop?

We even name our pain to assuage our oppressor.

Consider “microaggression,” once ethnic studies jargon, now social justice cliché. Every time I’m in a space with two or more people of the same race and gender, I worry I’ll mix up their names — that classic racial microaggression. At the same time, I notice my anxiety with disdain. Calm down.

But it’s worth taking seriously. The confusion of two people of color of the same race and gender sets the stage for the replacement of Asian people with virality, of Latinx people with virility, of indigenous people with savagery, of brown people with treachery, of Black people with criminality. The synecdochic mix-up scales up to a metonymic operation. Microaggressions are only micro to a people and a system that fail to understand the telescoping nature of their harm.

Even as we minimize our pain for the sake of white comfort, we often truncate our worlds to a history of white violence. We do it for the sake of legibility to the white gaze.

However, defining “people of color” as “victims of occasional racial violence” is a lose-lose proposition for our personhood. It leaves us either sufferer or fraud, but we are so much more than how they harm us or whether they believe us.

We exceed the gaze by measures beyond imagination.

“One way to know you’re in the presence of — in possession of, possessed by — a racial imaginary is to see if the boundaries of one’s imaginative sympathy line up, again and again, with the lines drawn by power.” Put plainly, the racial imaginary makes up stories about the Other that match the plots underwriting white power. That’s how Claudia Rankine and Beth Loffreda define the concept in their anthology of the same title.

To concretize: If another Asian person is walking toward me on the sidewalk, and I move onto the street to avoid infection. If a Black person walks past me in the parking lot, and I lock my car again “in case.” If a brown person walks into the elevator, and I gesture at the buttons instead of speaking English. In all of these cases, I am perceiving the person of color within a narrow grid, something like a cage.

According to Morrison, the white literary imagination is how white writers make use of Black characters while excluding Black people. The racial imaginary, h/t Rankine and Loffreda, makes clear the invisible frame for the creative act: the power and policies of a settler-colonial racial state.

The Georgia Bureau of Investigation arrested the two white men who killed Ahmaud Arbery on May 7, 74 days after his murder. The impetus, some claim, is the organizing that social media has facilitated, the very reposts I have bemoaned. The effectiveness is not exactly surprising. It actually proves the point. That social media can enable mass mobilization and political change suggests both the extent to which the white gaze governs American institutions and the power that’s harnessed when you move white people to outrage.

Oh Shaun, you social media lightning rod. As someone who’s edited my résumé to make my achievements measurable and myself hirable — consumable — I’m embarrassed by all these numbers in your tweet. Which fundraising expert taught you about SMART goals, and what are you getting for meeting them?

This tweet is also going around:

Viral content often lacks context. Every time I come across this tweet, I assume it’s about the arrest of Arbery’s killers. Only now do I notice the ways in which it’s almost scrubbed clean of historical specificity, written to outlast the moment perhaps. The “always remember,” an admonition made in anticipation. The use of the anonymous “they” and “we.” Is it Twitter’s character limit, or is it the power and presumption of whiteness to move freely across space and time? Only a white man would step so comfortably into the position of historical authority. Always remember.

People are also circulating the rhetorical opposite, the highly specific:

Yeah, okay. But also this switcheroo logic is characteristic of naïve understandings of white supremacy, patriarchy, and the rest of the gang. The hypothetical scenario is so unimaginable as to scuttle the point.

Two white men going viral for tweeting about a Black man’s murder — this is the clearest evidence I’ve come across that social media operationalizes the white gaze. That is to say, it puts into play white ways of making sense. It reifies, normalizes, and incentivizes ways of self-fashioning and community building that accord with white norms.

Every time I follow a thirst-trap account, click on the latest iteration of the latest unparsable meme, or write a reflective, raw, but ultimately uplifting caption to accompany my increasingly professional selfies, I reinforce a worldview in which I and everyone I love are lesser. This, even though I "curate" what I follow to only consume people of color.

That’s what the white gaze is all about: consuming people of color.

George Yancy makes clear what the white gaze does. He writes in Black Bodies, White Gazes:

As I endure those clicking sounds [i.e., of someone locking a car], I catch a glimpse of myself through the white person’s gaze. I am constructed as evil and darkness. […] As I move along urban streets, the white imaginary projects upon my Black body all of its fears, rendering my Black body the instantiation of evil. The distinction between signifier and signified have collapsed.

Yancy, philosopher, is describing a phenomenological process: what changes within a person as power acts on two people. Projecting and rendering, constructing and collapsing, white perception has the power to make and break people.

The literary imagination centers an isolated white subjectivity, one that stages the racial Other to tell a story about the self. The racial imaginary takes power into account. While focusing on the imagination limits a relational analysis, Yancy complicates both formulations. He tracks the fraught transaction between two coordinate subjects.

We actually have a term already that synthesizes what Morrison, Rankine, and Yancy are each theorizing.

The white gaze is a social medium.

4/

A tentative definition: The white gaze is a set of dialectical perceptual practices — filters, if you will — that inscribe a relation within the dynamics of white supremacy. (Doesn’t “followers” make more sense now?)

To illustrate, the white gaze:

- classifies/mixes up

- idealizes/demonizes

- exceptionalizes/essentializes

- coddles/objectifies

- de-sexualizes/hyper-sexualizes

- over-identifies/others

- overestimates/belittles

- demands care/evades criticism.

Case in point: Much of the reporting widely shared about Arbery’s killing describes him as a jogger. Yet people who run seriously would never say we “jog.” What does the difference reveal?

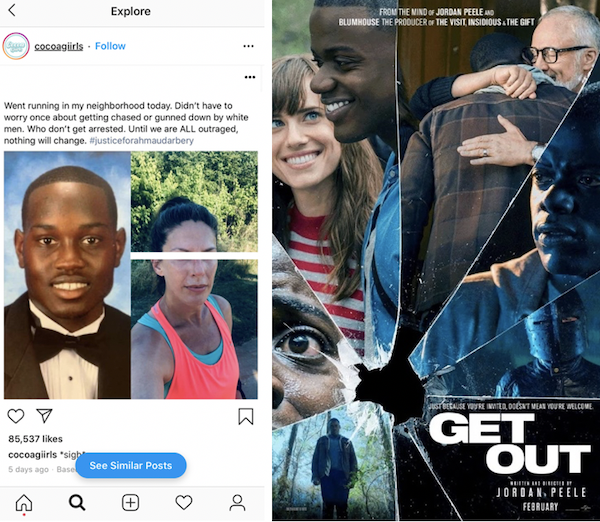

To the racial imaginary, the sentence “a Black man runs” raises questions like “What did he do wrong?” and “From what?” I don’t think these are the questions most Black people would ask if faced with this post:

But to the white gaze, “a Black jogger” is safe. Jogging implies leisure, which overrides the danger that the white gaze inscribes onto the Black body. The media, always ready to return innocent Black victims as the always-guilty Black criminal, preemptively decided that Arbery died jogging.

If a legion of social justice warriors runs in the streets, and no one takes a selfie, does the activism even occur?

Recall the “Black people are tired” meme. Probably the last thing many Black people feel safe to do right now is run in public. This outdoor action, like the online petition, does not seem to serve Black people.

Recruiting non-Black people to do for visibility what a Black person was killed doing — it would be an understatement to call it rubbing salt in the wound. It is un-empathetic, infectious over-identification. It is the discursive violence done when narratives about people of color center the white gaze. It is American Dirt.

As far as I can tell, the tension between Run With Maud and shelter-in-place has gone unnamed. This, despite the posts some are making to shame people breaking quarantine. What’s going on?

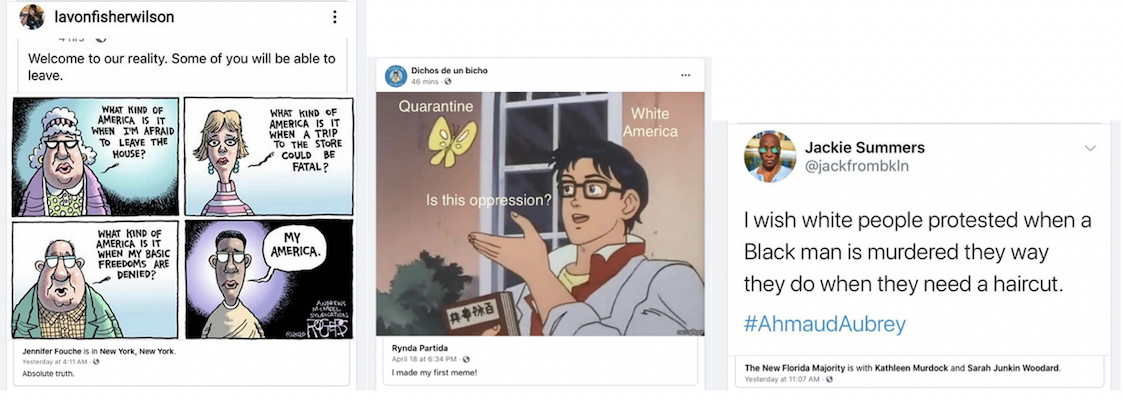

Social media delights in exposing the cluelessness that results from segregation, as this trio of posts shows:

With that said, social media lacks the capacity to integrate realities. It tends to acknowledge crises one at a time. This has the effect of partitioning realities: anti-Blackness content here, pandemic content there.

So let us put two and two together. The “I Run With Maud” action calls for masses of people to go outside when science advises against it and many governments forbid it. In addition, anti-racist reporting has proven what many already knew. Because of preexisting systems, this pandemic disproportionately harms and kills Black people.

What does this amount to? A campaign named after a Black man that by no means seems to be for Black people — made possible, of course, by social media. In other words, non-Black people leveraged the grief around a Black catastrophe to seek relief from the global one.

I take a Pomodoro writing break and go on social media. This again:

I make the mistake of scrolling through the comments. Non-Black people talk about Black death like it’s nothing.

5/

Today is May 10. Another Black icon has died: Betty Wright. Yesterday, Little Richard, and on May 7, Andre Harrell. I think about posting something on social media about what a mournful week it’s been for Black people. I decide against it.

From posts by Black writers and journalists, I glean that these artists have shaped the world in ways that many non-Black people will never recognize, myself included.

Another piece of Black knowledge that I learn during the pandemic: the adage “when white folks catch a cold, Black people get pneumonia.”

Black excellence and anti-Black racism are both conditions of possibility for modernity. A corollary of that proposition — a generalization, I admit: Black people are positioned and poised to identify the fallacies and foul play of the modern world. This sociopolitical arrangement might be news to some non-Black people. Our ignorance is often a burden and a harm to Black people. How do we reduce or even eliminate it?

I think about ending this essay with action steps. Chalk it up to my Virgo MO.

I write that ending. My partner reads it.

He says I’m pandering to the white gaze.

I’ll speak to us instead. We East Asians long to surpass the role of white supremacy’s side piece. I mean, we are yearning for self-determination and agency. The turn from white adjacency circulates as hashtag: #NotYourModelMinority.

Our desperation is very human and very deep. To my mind, it explains why some of us perform what we take to be Black culture, publicize our proximity to Black people, and tally our pro-Black acts. In an anti-Black nation still defined by the Black-white binary, the most legible way to defy the racist order is to align with Black people. If this sounds exploitative, it often is. Legibility, after all, is prerequisite to marketability.

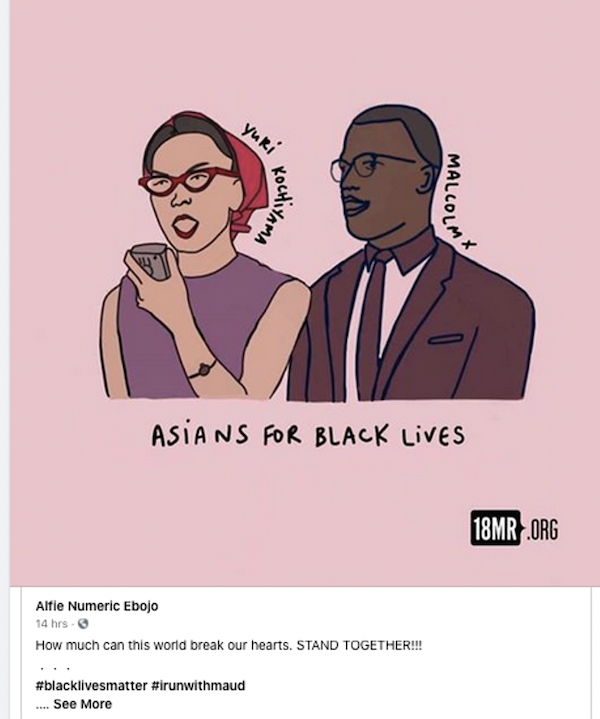

18 Million Rising is selling a T-shirt to fundraise for Black- and Asian-led grassroots organizing. The illustration:

Five or six years ago, I would have bought this in a heartbeat. At the time, I was teaching English and ethnic studies at a majority-Latinx high school. I was one of two Asian American male teachers on campus. Desperate not to be mistaken as the wrong type of Asian, an honorary white, I amassed an array of social justice-y T-shirts. I even bought the one that DeRay made viral. It says “I LOVE MY BLACKNESS AND YOURS.” Thankfully, I never wore it.

Now, in 2020, I pass on the new look. If the shirt serves anything, it’s the image of the person wearing it. It’s the worst of both worlds: IYKYK and IKYKNYKIK. This self-boosting function appears in the design itself. For one, the man in the drawing looks nothing like Malcolm X. Dude looks more like Chidi Anagonye than the actual Black radical. Meanwhile, Kochiyama looks spot-on and bad-ass. She speaks, amplified, while the former Mr. Little is off to the side. It may simply be that the Yuri drawing reproduces a well-known photograph. While that might be the case, there’s another well-known photo. It’s Malcolm holding a rifle by the front window.

This unfortunate illustration might as well be captioned “NOT YOUR MODEL MINORITY.” It paints Asian Americans in a powerful light, Yuri literally ahead of Malcolm X, in order to prove the white gaze wrong.

A second Rorschach test:

Every aspect of this activates me. It’s less the anti-Asian sound bites than the characterization of “my Black friends” as ignorant and hateful to imply the saintliness of certain Asian Americans. I don’t buy the implied ratio of xenophobic Black people to activist Asians. Maybe this incredulity is particular to me, an East Asian man who has made more Black friends than Asian ones precisely with the premise that Black people get it and East Asians don’t.

People who might otherwise meme the Audre Lorde quote about single-issue lives are, in this staggering moment, treating two US institutions — forever foreignness and anti-Blackness — as if they weren’t ordered by a third: racial segregation. If there are Black people scapegoating Asians for a global pandemic, if there are Asians victim-blaming Black people for state-sanctioned violence, their respective ignorance certainly has to do with the endless impersonal forces that make us strangers to each other. It has to do with the social distance.

Segregation is not only spatial. It is ontological: don’t say that/wear that/be that because it doesn’t belong to you. In turn, it’s also epistemological: don’t think that/cite that/write that because it doesn’t apply to you. People put up gates to protect the resources presumed most scarce.

Scarcity has spiritual consequences. When we internalize the myth that there isn’t enough to go around, we risk falling for the premise that we are not enough. And when we believe that our lives are worth less, we treat the suffering of others as worthless.

When we fight for the scraps they set aside, it’s white people who stay fed. When we stay in the lanes they painted in the dark, it’s they who weave and wile out, boundless, lawless.

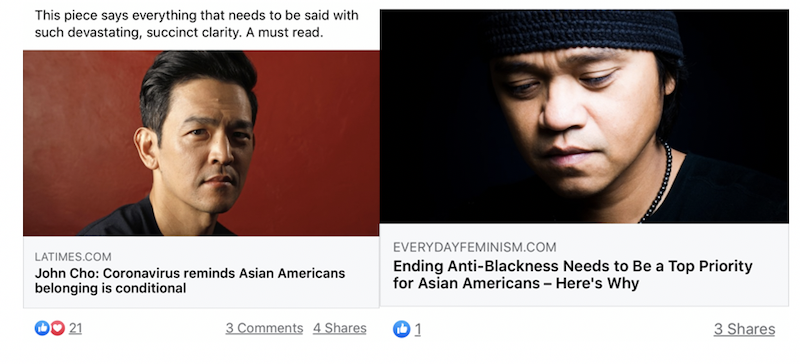

Last test. Back in late April, because of scarcity, my Facebook feed looked like this:

For some Asians, it was novel to note we're not actually white. Surprise! Then there are the Asians who can't stand them: their vestiges of whiteness, their complicity. Lest they're confused for the wrong kind of Asian, they brand themselves as the diametric opposite: the Angry Asian Man.

I’m no longer novice or saint, but I remember the confusions and wounds of both. Social-justice-oriented Asian Americans make strawmen out of everyone else because of resentment. I feel it too. If I ever let it out, here would be my cry:

All that we want is to be called brothers and sisters for once! I mean, siblings! And it’s because of all those white-aspiring Asians that we’re always left out. So, John Cho, stop telling Asians to feel bad because of COVID. Anti-racism isn’t for us — we’re the racists!

Because of scarcity, people have posted about the more episodic violence of anti-Asian racism and the more structural violence of anti-Black racism as if we can’t acknowledge both at the same time. The fear: paying attention to everyone will somehow bankrupt the sources of recognition, maybe even nullify the currency already paid out.

Remember the Woke Hapa? He shared a Facebook post that illustrates this fear. It’s addressed to “my Asian (esp East Asian) family.” In case the post is not quite public, I’ll paraphrase. Please bracket your pain, however shocking and unfamiliar, so that you can learn about other communities’ ongoing suffering.

It’s probably fine to leave out the screenshots because the post sounds a lot like me. I find the writing insufferable, and my repulsion has to do with my identification. The specification of East Asian to signal awareness of the inequities within Asian America, the listing of systemic oppressions to demonstrate ethnic studies fluency, even the affirming parenthetical at the very end — “I see you!” — I recognize these rhetorical moves so keenly because I use them all the time. I want people to know what side I’m on. Likewise, the post is a perfect recitation of every social justice script. Yet the bad Asians it’s explicitly addressing wouldn’t pick up on all its cues. So who are its people? What communities does it serve?

Not Asian Americans. The post fulfills expectations to get some thumb-ups and bubble hearts. That is to say, like much social justice discourse nowadays, it’s for the white gaze that wires us all.

Even when we create “for the people,” we can end up speaking past our own — even when no one is out there at all.

6/

Today is May 15. I drafted the bulk of this essay last week.

This week, as I revise, I use social media much less. I would like to think it's because of everything I'm writing.

I do post once on Facebook. It is short, witty, and positive, of course. It’s the most likes I’ve ever gotten.

People comment congrats. I would like to think they’re celebrating all three of my successes and not just the model minority one.

I’m on day two of my tattoo’s healing. It’s a black panther embraced by a banner, which reads: “SERVE THE PEOPLE BY ANY MEANS NECESSARY.” The artist is Japanese American and pulls from his traditions. IYKYK.

A friend comments, “OH MY GOD HOW CAN YOU NOT SHOW IT TO YOUR FANS?”

“LOLOL It’s literally a bloody mess right now. Not on brand! But soon.”

I would like to think I’m joking.

I don’t know whether I’ll post a photo once it’s good to go. I love it — it’s very me. I also know that most of it’s not mine. I fear judgment, call-out, and condemnation for what I’ve made a part of my body.

I heal, and I do. Flowers float near panther’s claws, tail taut. I wear our histories as horizon line.

¤

Brian Lin is a PhD student in the creative writing and literature program at USC. His work can be found at Hyphen Magazine, Lambda Literary, and The Margins. He has participated in the Tin House Summer Workshop and the Napa Valley Writers’ Conference and is a 2020 Desert Nights, Rising Stars fellow and a 2021 Ragdale resident. Brian is fiction editor of Apogee Journal and is working on his first books of prose.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

What If We Saved Ourselves?

Brian Lin maps out the terrain of racial struggle in the literary world.

“This Constructed Self of Mine”: On the Narrative Possibilities of Racial Melancholia

Kim Hew-Low on the ways BIPOC writers assemble their stories.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2021%2F03%2FQJLinViolence.png)