¤

JENNIFER SEAMAN COOK: It’s interesting that you started talking about access to the mimeograph as new but not complicated technology, because the first question I had was how you are considered part of the mimeograph revolution and what you really think that did.

ED SANDERS: Well, access to these small, portable mimeograph machines that were mainly used by churches and peace groups in the early ’60s — in the Ban the Bomb movement it was very big, the Civil Rights movement, Congress of Racial Equality, and Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee — they all had mimeograph machines in their offices, which could quickly turn out leaflets and brochures and pamphlets and time schedules right away. There was no photocopying then, it was before photocopying, and there were no cassette tape recorders back then, so the mimeograph was the current, state-of-the-art way of producing quick leaflets and flyers. So I was hanging out at the Catholic Worker in 1962. My friends worked on the Catholic Worker newspaper, and in February of ’62 I purchased a $39 or $40 Speed-o-print mimeograph machine — a real small thing. I had an apartment in the lower east side that had the bathtub in the kitchen. There was a porcelain cover over the bathtub, and that’s where I put my mimeograph machine when I brought it in February 1962 and started publishing a mimeograph magazine, which I typed up at the Catholic Worker, because I didn’t have a good enough typewriter to type stencils.

So I borrowed the Catholic Worker’s typewriter and started putting out a magazine and started mailing it out all over the world, and it became quite famous in its day. So that was the state-of-the-art technology. A few years later, when what they called the underground press started, there were printing facilities in many cities that printed used car bulletins and flyers for supermarkets, but they were willing to sell you a little space, a little slot in their printing schedule. So all across America grew up this thing called the underground press. Web press they called it, and they printed off big rolls of newsprint, and it made possible the underground press because you could rent a two-hour slot at these web press sites. In between their car ads and their newspapers they were already printing, you could put your radical and revolutionary underground press, such as the Los Angeles Free Press or the Berkeley Barb.

So a lot of the early alternative press movement … actually was in part this convergence of the counterculture and the actual structural aspects of classified ads, which I think is very interesting. I’m thinking back to when you published the “Vancouver Report” …

I gradually converted from my little handheld mimeograph to an electronic mimeograph when I opened up to the Peace Eye bookstore in early 1965. I’d printed little publications, such as the 1963 “Vancouver Report,” which was a report on a literary festival held in late ’63 in Vancouver that featured Allen Ginsberg, Robert Creeley, Charles Olson, and many other poets, Robert Duncan, I guess, too.

Do you think that part of the mimeograph revolution that you’re credited for was seen as the socializing media of the mimeograph and bringing it to socializing poetry, or a cultural movement? How do you see it now versus what you were thinking of doing with it in the moment?

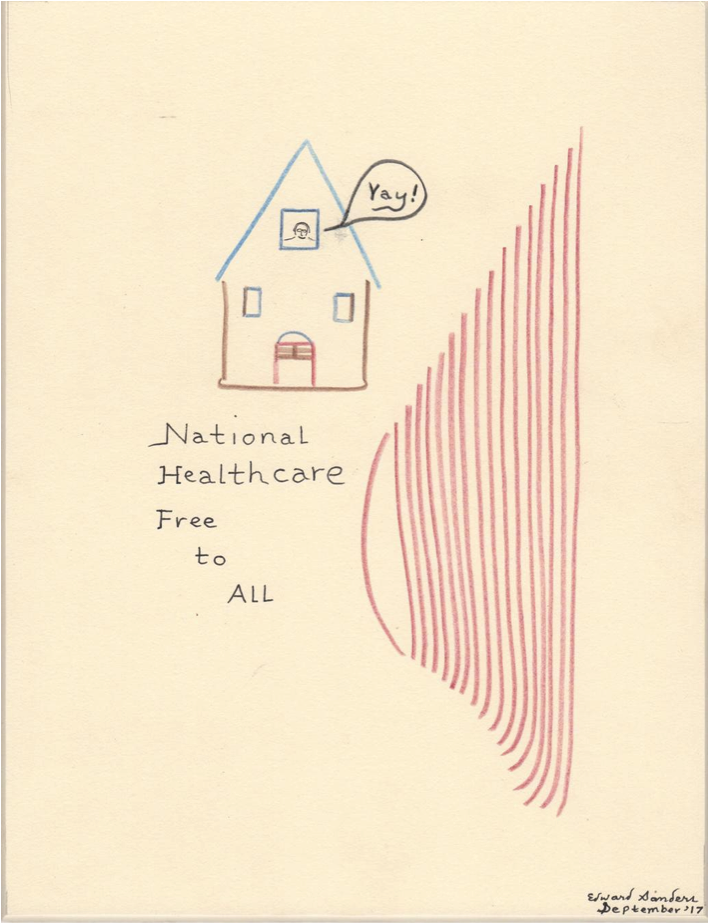

We were interested in nonviolent revolution, you know. We thought that when we were old we could forge change in the United States, so that there was universal health care for everybody, guaranteed annual income, good pension, a month’s paid vacation. You know, in Europe if you work for McDonald’s in Sweden you get a month’s paid vacation. Very few people get a month’s paid vacation in the United States. Anyway, we thought all these changes would come. We were kinda wrong, but we had youthful hope that it would lead to vast change.

Using mimeograph machines and later web presses, and with the advances in recording from two to four to eight track, [it] mirrored what we were doing in the mimeograph revolution — they were going from two track to four track. The Beatles recorded most of their main albums on four track, and it was only at the end of their career in the late ’60s that eight track and then finally 16-track recording came in. So there wasn’t all this technological … movies: they were using 16 mm cameras — the Bell and Howell, and Rolex — and Andy Warhol shot in 16 mm film mostly, and only gradually at the end of his career did 35 mm, professional, Hollywood-level shoots, but most of it was stuff you bought cheap, at Willoughby’s … or, there were a lot of camera stores in New York City — Willoughby’s and others where people bought their cameras.

That brings me to how you were, in your work with the Fugs, establishing these relationships between music and experimental poetry, New American poetry, and what would now be considered avant-garde print media — which, really, we’re talking about avant-garde uses of alternative press media. I was wondering if, at the time, you saw the work as part of the larger social possibilities of the mediums, or if were you trying to just build something around you, expression, a community? Did you see art and poetry as being able to shape something within a social movement alongside alternative press media, or did you see it as happening organically, almost as if you were documenting all this intermedia mixing that was happening organically?

Well, the Civil Rights movement, the antiwar movement, the Ban the Bomb movement, and the general pro-pot movement, and various other movements were forming … and there was the Happening movement, where you could rent a storefront and you’d get a bunch of people, you’d get someone to take off their clothes, and you’d get a stock tank full of grapes, and you’d get people to dance on the grapes, and have somebody reading poetry and you’d bring in a cow and paint it and you’d call it a work of art. And you could charge admission, so the issue was making a living through your art.

So the Happening movement coincided with the Civil Rights movement, all these great songs like “We Shall Overcome,” and “Down by the Riverside,” and “I Ain’t Gonna Study War No More” — all these great Civil Rights anthems — combined with the fact that, in these apartments where I lived in the Lower East Side, there was usually a guitar in the corner. People always sang together. There were all these three-chord songs. You’d sing Joan Baez songs but also Civil Rights songs, and then, finally, when the Beatles showed up in 1964 you could sing Beatles songs, and guys like Richie Havens and The Lovin’ Spoonful. There were various groups that led this thing that became folk rock around 1965, 1966, and Jimi Hendrix burst forward in ’67. He got one of the first wah-wah pedals, which was an American invention — a guy invented this way of modulating a guitar — and I was around when Hendrix got his first wah-wah pedal and he took it over to London in late ’66 and the rest is history. He made musical history.

Right at the same time as Hendrix was first using the wah-wah pedal, eight-track and then 16-track recording was coming, so that you could overdub. Early jazz players like Charlie Mingus and Charlie Parker didn’t have a chance to overdub, so it was part of this culture of spontaneity, all these great jazz albums … they were one take only, or they’d do two takes for the whole album and pick the best one. By the late ’60s, you could overdub. The Beatles could slow stuff down and add drones, and add Indian instruments and experiment with overdubs.

So it was quite experimental, and people would feed off the films, would feed off the music, the music would feed off the Happenings, then there was the modern art … Willem de Kooning, Warhol were great innovators. Andy Warhol used to come to Fugs shows all the time. He was always out there to get ideas, and he made the banners for the opening of the Peace Eye bookstore. He silkscreened his flowers, his famous flowers from 1964. So Warhol was a friend of the Fugs, and it was a lot of cross-pollination between the Civil Rights movement, the Happening movement, the mimeograph movement, the rise in recording technology, and also the rise in sound reproduction. In order to do Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young in ’69, they had to develop a whole new generation of speakers, because the four-part harmonies were blowing out all the speakers, and they would play big halls but also became so popular they could play big outdoor places.

So the technology to reproduce sound grew, which made possible the Woodstock festival of 1969 — this new technology where you could play rock ’n’ roll for 500,000 people and not blow out the speakers. So there was all this technology rising at the same time as artists were rising.

You’re describing this culture of spontaneity coming out of both access to amateur media and the time and space for experimentalism. But it seems like you’re also describing developments tied to intention … toward creating spaces and events of collectivity, creating alternative economies that connect the cultural movements to the social movements, and also organizing important protest events. I’m thinking of your time with the Fugs and how you were part of several important public countercultural events in 1967 that arguably mobilized national and transnational political resistance, and arguably contributed to the momentum of the revolts in 1968. I’m thinking specifically about Perception ’67 …

Oh, Toronto?

Yes, and I’m thinking of your exorcism as part of the March on the Pentagon, and I’m thinking about the Angry Arts Week, and, again, all the intermedia movements that were part of Angry Arts Week. So I was wondering what you had to say about this network of artists and activists, artists as activists … what you think was accomplished versus what you had hoped would be accomplished, because we’re upon an anniversary of 1968. It’s seen as a kind of culminating period of what happened before 1968 and also this kind of wave cresting, the decline of movements afterward, but maybe you reject this idea.

1967 was an interesting year. It contained this interlude called the Summer of Love, where in San Francisco and New York City — but also places in the Midwest where the Fugs toured — there were these love-ins. We would go to little towns in the Midwest on tour, and there would be a crowd of younger people who were holding a love-in. And there was a love-in in Central Park. Then came the fall of ’67 and the war wouldn’t end. The CIA killed Che Guevara in early October in Bolivia, and the war wouldn’t end. So we decided to hold a demonstration at the very heart of the war — that is, right at the Pentagon. And the Fugs were charged with organizing an exorcism of the Pentagon — which we did — which involved members of the Diggers movement in San Francisco such as Michael Bowen and others. I wrote a ceremony to exorcise the Pentagon. You know, “Out, demons, out. Out, demons, out. Out, demons, out,” and we chanted it over and over in front of the Pentagon, and it became a world-famous event.

To this day, I have camera crews who want to come from Europe to talk about this exorcism that my band did on October 21, 1967, but I point out that, yeah, we did levitate the Pentagon — it worked — but we forgot to rotate it. And the war went on for another five years. So the Vietnam War didn’t end until 1975, so our exorcism was symbolic, but not really efficacious. But it helped trigger off [other movements] — of course Martin Luther King Jr. had come out against the Vietnam War in 1967, and was leading a lot of the religious aspects of the American social movement to come out against the war. Most Americans still approved of the war in Vietnam when we did the exorcism in October ’67, but by ’68 the movement against the war was rising ever higher.

Then, of course, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in April and Robert Kennedy was assassinated on June 5, 1968, which put an end to a lot of the momentum of the ’60s. They always say Charles Manson ended the ’60s, but what ended the ’60s was the evil assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and the evil assassination of Robert Kennedy. If they had lived, America would be different now. The war would have ended much sooner, and over 20,000 American boys wouldn’t have been killed, the number of those who died between 1968 and the end of the war.

It’s a terrible thing that happened in 1968, but there was the big rise up in Paris, the big, big, big, big student revolt, and also the farmers demanded better pay in France, and they won concessions from the de Gaulle government. Then there was a huge riot in the streets of Chicago during the Democratic Convention, mainly in response to the assassination of Robert Kennedy and the futility of what the Democrats were doing. The Democrats were — like they are now — they were supportive of war, in good part. So Robert Kennedy was part of the antiwar Democrats and he was assassinated, which gave the pro-war Democrats the upper hand. In 1968, though, there were a lot of great things, a lot of wonderful music and jazz, cultural festivals.

I remember going in ’67 to the Toronto Perception, and just as we were landing at Toronto the captain came on and said, “It’s minus five in Toronto,” so it was very cold.

And this wasn’t really an opportune time to have a festival, but wasn’t it in response to the Expo ’67?

Right. So it was okay. Timothy Leary was there. The Fugs gave a good show, and we had a lot of partying and fun.

This was more of a lysergic acid festival than it was a protest?

Yeah, it was more of a cultural event than a protest event.

But you bring up the assassinations of MLK and Robert Kennedy, and one of the questions I have is whether you see their assassinations as instrumental in cutting off a timeline of possible progress in the United States, not just because of their antiwar positions but because they were profoundly invested in bigger conceptions of a non-instrumentalist society, culturally and socially and politically.

I agree.

It ties into a lot of these artists’ movements.

Right. Now, they were a part of the good side of America. America is a great nation, and has many wonderful things about it. One of the unfortunate aspects of America is that it has a military-industrial complex that Eisenhower spoke about in his final speech. And this military-industrial complex that he complained about in his final speech is still running a great part of the show. We live here in peace (from war). None of us invade any countries, none of us drop napalm, none of us drop defoliants. It goes back to the generals demanding to drop the A-bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. That’s the source of a lot of the evil aspects of the United States. I mean, I call myself patriotic because there are many things about my nation that I love. Those things that I abhor I have to struggle against nonviolently, because I grew up in the nonviolent struggle of the early ’60s that Martin Luther King was a great example of — he called it “unearned suffering,” the realization that you have to suffer in order to try to do good.

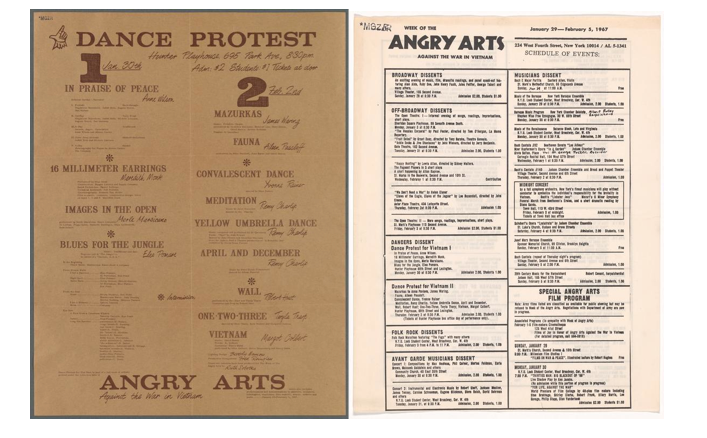

Angry Arts was well organized in New York City. They had committees and they put out really good literature, good schedules.

You know there’s that line in Allen Ginsberg’s Howl — “I saw the best minds of my generation.” And that was part of the marching orders of my group in the ’60s, to find the best minds and cross-pollinate with them. Find the best dancers. Find the best guitarists. Find the best artists. Find the best writers. Find the best leaders. Find the best activists. Find the best technicians, sound recording people, recording studio people, movie people. Find those and cross-pollinate and see what you can come up with. And Angry Arts was a result of this: a lot of active people who were angry about the war in Vietnam and decided to take a stance against it.

But there was also, in New York City, a tendency to ban certain cultural events. There was a law that prevented poets from reciting in restaurants. There was a cabaret card that you had to get in order to perform at nightclubs where there was drinking. So Lenny Bruce lost his cabaret card. Billie Holiday lost her cabaret card. And, then, before the World’s Fair of 1965, the city government of New York decided to clean out its counterculture and to clean out poets who read in coffee shops. There was a whole group of city bureaucrats who were trying to stop coffee shops from having poetry readings. This was what we learned later was an attempt to clean up the city preceding all the tourists that would come for the World Fair in 1965. So we had to fight against that. We had picket lines and protest lines and letters to the editor and we were all trying to stop this squashing of poetry readings in coffee houses. You know, it was ridiculous.

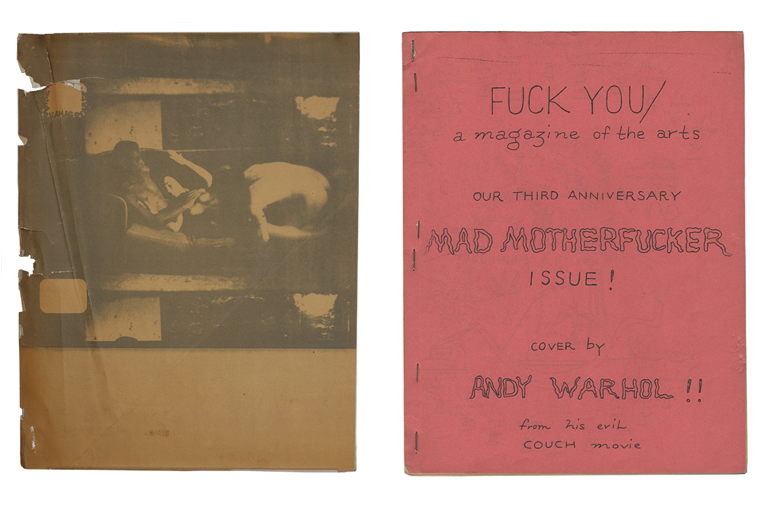

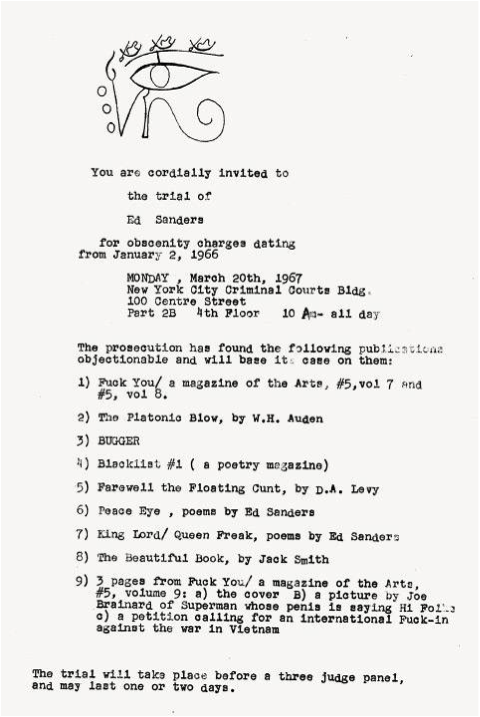

And then there were movies. Jack Smith, Flaming Creatures (1963), and there were other movies … a Jean Genet movie that was censored. So they were always trying to censor. And my magazine, Fuck You: A Magazine of the Arts, was [censored] — my bookstore was raided in early 1966, and I had to get the New York Civil Liberties Union to handle my case, and finally I won a year later, but I had to [go to] court like 10 times to get a victory against the police who raided my bookstore and carted away a whole bunch of my magazines, including the “Vancouver Report” and other publications I put out. I finally won, but it took a lot of effort and fundraisers. I had to raise money to pay for my defense and so forth.

So it wasn’t automatic, you know. You didn’t succeed. It wasn’t a cream-puff gig. It was a difficult march, a difficult progress in the ’60s to prevail, to open up voting. After the death of Kennedy, the Civil Rights law was passed, and Johnson passed the Medicaid law and the various Great Society legislations, and this all came about after the assassination of Kennedy, these social laws to quell and keep down social revolution, because there was danger of outbreaks of violence. So they passed these laws to calm down the masses.

I’m thinking of the political threat of counterculture to social norms that you’re describing … the threat of reciting poetry in a cafe … or I’m thinking about the extreme hostility during the Trial of the Eight after the Democratic National Convention. Allen Ginsberg, when he’s on the witness stand, when he’s asked to recount what happened, starts going into a chant — his Om chant — and how threatening the courtroom found that, that he was doing a poetic demonstration in the courtroom. These kinds of counterculture [activities] are political in a way because they keep social norms fluid. It reminds me of Ezra Pound, how he wrote in the ABC of Reading that what literature does versus journalism is that literature stays news. He says “literature stays news,” and that what poetry does — or you could argue poetics, media poetics, intermedia does — is that it keeps subject matter from becoming history and it keeps it immediate and it keeps it circulating. And maybe this has to do with the way we almost erroneously see this separation between cultural and social movements, or maybe what was successful and what failed.

Yes, Pound says poetry is news that stays news, and there’s some truth to that. He also had the phrase “make it new.” Well, you make it new, but you keep the roots of the good part of the past alive too.

In 1976, you wrote a manifesto for Investigative Poetry, published with City Lights books. Do you see a kind of renewed value for Investigate Poetry in our time in this so-called crisis of Fake News? I’m specifically thinking about how we have some of this fallout from media decentralization. Maybe it does have something to do with the alternative press movement, but it’s led to ideological thinking along the lines of very anti-democratic communities. So we’re talking about threats to some of the important traditions of our institutions, and we have reports … opinions toward journalism and hostility to free press threatens to dissolve rather than reform or change institutions. So I guess it’s also a question about not just levitating, but rotating something, maybe.

Well, there’s a basketball term about throwing it up for grabs. I guess it’s called the “alt-right.” I don’t pay much attention to the alt-right, but they want to throw it up for grabs and create a more rigorously right-wing republic, and do away with democracy, in a way … Keeping voters from voting, and keeping blacks from registering to vote, and keeping poor people from registering to vote. When the republic was formed, only male landowners were able to vote, and that’s probably what some of the alt-right would like to have happen, just a bunch of guys getting in a smoke-filled room and voting, but that won’t happen. There’s too many people who believe in the American Constitution to allow this decimation of voting. Voting is very important, and sometimes, as happened in 2016, somebody weird can get elected. We all just have to rise up and deal with the weirdo that gets elected now and then — not always, but billionaires pour hundreds of millions of dollars into American elections, so it’s remarkable they don’t elect Mussolini, you know?

Look, kids don’t know Allen Ginsberg now. I gave a talk at the University of Michigan a couple years ago, before 200 people … and I talked about 1968, and I talked about the Yippies and the riots in Chicago and this and that. I talked about the revolution in France. And this guy comes up to me after my presentation, he says, “Professor Sanders, Allen Ginsberg, he was one of the lawyers at the O. J. Simpson trial, right?” And I say, no, wrong, and I explained who Allen was. He was a young kid from the Midwest and he had not been taught about it. We lost the battle of the textbook, I guess that’s what I’ll say. Allen Ginsburg and the Beats, they are a presence in American education, but they’re not featured in the expensive textbooks that high school kids buy.

Do you think cultural institutions have an ability to compete with this kind of political money anymore, compared to the really robust funding we had when a lot of the new Americanist poets came through really well-funded public universities? This is just an example. Maybe if we can’t compete equally in terms of resources, in terms of the structure of campaign financing, can we turn back to relationships between art and politics, between cultural life and social life?

It’s hard to know what could happen. As we sit here talking, Trump is threatening to shoot missiles at Syria. And Russia has said it will respond to any of their soldiers being killed by targeting the sources of American missiles, submarines, and destroyers located in the ocean. So if America bombs Assad from American ships and Russia attacks and destroys American ships, does that mean World War III will happen? And that could happen this evening as Cassandra gets performed. So nothing is certain. It’s a very perilous time, and the Military-Industrial Surrealists — I call them — the Military-Industrial Surrealists are threatening World War III. So we’re in a comfortable meeting room in a nice cultural center waiting for my play to be performed tonight with the world holding on the balance of survival.

I’m thinking about how we got here and I’m thinking about something we were talking about earlier, off tape, these audio interviews that no one listens to, and the need to go back and transcribe these things. Marshall McLuhan described World War III as a mass information war where there’s no distinction anymore between the public and the military. Is part of what’s going on with the threat of nuclear war tonight that war of information or a war over people caring about it?

There’s been a big militarization of the United States, jet fly-overs of football games. Up where I live in Woodstock, New York, there are billboards: “Help the army win.” Big, huge billboards. There’s a huge militarization going on, plus the defense budget … they can’t possibly pay for it so they just borrow money to pay the American military with bases in 500 countries or 500 bases here and there …

In 1961, you wrote “Poem from Jail” on a piece of toilet paper. There’s this trajectory of you going from this — what’s considered one of your first significant poems — to Fuck You, and later, writing a history of America in verse that was distributed on CD. Does that legacy of something that started on a piece of toilet paper say something in the face of this massive information war that Allen Ginsberg was talking about in “Wichita Sutra Vortex,” which is this inability to deal with the ideological war machine on the radio?

Well, I wrote it on toilet paper because the jail in Connecticut wouldn’t allow paper, so just like the mimeograph was the method of publishing at a certain time in my life, so too writing on toilet paper was a method of taking down my thoughts and laying out a poem I was writing. It’s so long that the toilet paper was hundreds of feet long and I wadded it up and smuggled it in my tennis shoe in the jail because they didn’t allow you to write. They didn’t allow you to have pencils. They didn’t want us to talk about conditions in the jail.

You use the tack you can, that you have. I suppose if there was no paper I’d get a piece of crayon and write on the sidewalk like they do in Paris, street poetry, street art.

¤

Jennifer Seaman Cook is a published American Studies scholar, essayist, creative writer, and documentary media maker. Working at the intersections of politics and poetics, she specializes in visual and public cultures, cultural and social movements, and media and technology studies.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

Thinking with Martin Luther King Jr.

Shivani Radakrishnan reviews by “To Shape a New World,” a collection of essays edited by Tommie Shelby and Brandon Terry.

Framing 1966: Jon Savage on the Year the 1960s Exploded

Scott Timberg takes a spin through “1966: The Year the Decade Exploded” by Jon Savage.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2018%2F07%2FCookSanders.png)