All photographs by Helen Mackreath. All rights reserved.

In the first place, we don’t like to be called “refugees.” We ourselves call each other “newcomers” or “immigrants.”

— Hannah Arendt, “We Refugees”

¤

SHATILA CAMP in the southern suburbs of Beirut is awash with a poverty of classification. Men brandish raw almond fruits with pistols poking out of their back pockets; motorbikes upend cherry carts; large groups of men and women gather around sweet parlors. This was once just a camp for Palestinian refugees expelled from their homeland, whose application to international humanitarian law is easy to categorize:, Shatila Camp is also the site of the brutal massacre and desecration on 16 September 1982. But today, the categories are all scrambled. Palestinian Syrian refugees also live here now — individuals who have been displaced twice as a result of conflict (another seemingly straightforward act of classification). Other individuals are less easy to categorize. “A thing can be two things at the same time,” said John Berger. “A table of wood and a sledge. A hook and a beak.”

Down a narrow opening between two compounds and up some steps, in a concrete block perched atop another home, lives a Syrian family, a grandfather and grandmother, an uncle, a son, and three daughters. They too sit at the ambiguous junction of classifications: a migrant worker and his family who had been forced out of their homes by the conflict, identifying both as voluntary economic workers and forced political victims. Who is the hook and who is the beak? The uncle, a migrant, has been living in Beirut for nine years, working as a baker. His brother works in the Democratic Republic of Congo (migrants are not only Westbound), also as a baker, and sends reparations to his family first in Syria, and now in Beirut. The nephew, a gentle boy with very soft brown eyes, has found a job in a bakery in Beirut through his uncle.

Dignity is a powerful need. The family does not identify as a refugee family — they earn a living in a similar manner to how they did before the conflict, and do not accept international humanitarian assistance. Their hospitality is lavish, proffering coffee to visitors. The nephew plays lovingly with his young sister. The older men discuss the politics of the camp, and Syria. They play on their phones. The grandfather surveys the horizon of satellite dishes and a matrix of concrete boxes. This is a home bounded by hard work, love, and integrity.

¤

A neat game of smoke and mirrors is being played in Europe. “Syrians fleeing the country’s civil war for the UK are illegal immigrants not refugees,” Janice Atkinson, a former Ukip MEP, says. “A man who leaves Syria may be a refugee at the start of the journey. When he is illegally living in Calais and illegally attempting to enter Britain he is an economic migrant and an illegal immigrant.”

“People now seeking sanctuary in Europe should be seen as immigrants, not as refugees,” says Viktor Orban, Hungary's prime minister, who is in the process of erecting a razor-wire fence on the border with Serbia, fast-tracking legislation to establish a zero-immigration regime, and deploying the army on the border. Why? “Because they are seeking a ‘German life’ and refuse to stay in the first safe country they reach.” International legal protection afforded to people fleeing death is suspended if they do not hold to the land on which they beach, they argue. Fertile life is being granted to academic (some would say gratuitous) debates over semantics.

It is now common practice in Europe to enforce a heavy-handed, arbitrary categorization of those fleeing war. One family arrives 30 seconds too late to squeeze through the closing gate between Hungary and Serbia, but another gets in during the 10-minute delayed closure. Syrian refugees are currently being privileged over equally destitute refugees from other countries. One group is not more worthy than the other.

The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees specifically separated “refugees” from “migrants” in response to the fascism and nationalism in Europe of the 1930s and 40s. Before then, migration, and integration into the labor market, had been seen as protection for refugees, and the two terms were intentionally conflated. The Nansen passport was adopted in 1922 precisely to facilitate the process by which refugees seek employment and, in effect, become migrants. In 1926 the International Labour Organization Refugee Service reached agreement with the state of Sao Paolo to accept 265 refugees a month, a number that was to include 15 locksmiths, five stucco plasterers, and five bootmakers. The UK’s European Voluntary Worker (EVW) program presented EVWs as both workers and refugees, combining productivity with need. But international migration, and refugee asylum along with it, was unpopular and restricted following economic depression and the rise of the far right. In a 1938 U.S. opinion poll, 94 percent of Americans disapproved of the Kristallnacht anti-Jewish pogroms, but 77 percent thought that immigration quotas should not be raised to allow additional Jewish migration — humanitarian sentiment was replaced with the perception that all fleeing Jews were “migrants.” There was a need to distinguish and prioritize those people requesting asylum from conflict and persecution. Today, the far right is succeeding in scrambling the terms to shrug off responsibility. But the truth that the two are intertwined, that mixed migration is a reality, has more complicated implications than denying entrance.

Back in 1985 the International Council of Voluntary Agencies (ICVA) and UNHCR hosted a workshop on “Development Approaches to Refugees.” It aimed to detach the refugee from his/her assumed powerlessness, and to find new ways of absorbing refugees in host countries that recognized their worth, not their helplessness — a movement back toward recognition of their “migrant” qualities. It’s still a controversial area today. Work on a 2014 UNESCWA report on the positive impacts of forced migration in the Arab Region was impeded by a lack of commitment to that ideal. Singing the virtues of migrants, and refugees, is not necessarily popular among state governments.

¤

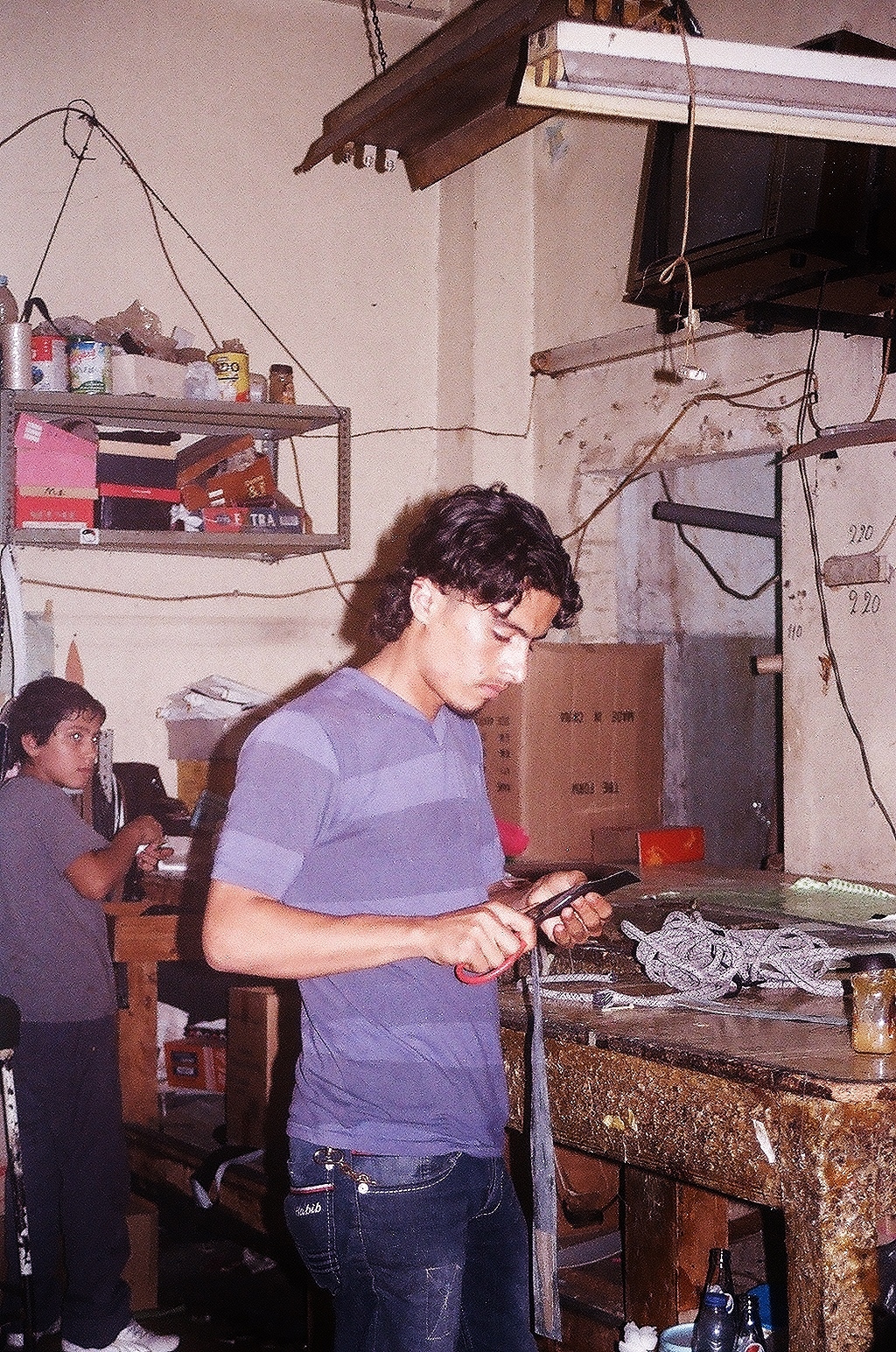

In Qobayat, a Christian village in North Lebanon, refugees are viewed quite unapologetically as an economic chance. “They are a business opportunity,” say the landlords. They pay rent for small white-washed homes and work as laborers or in hardware stores. No other welfare net exists here. In Bourj Hammoud, the Armenian quarter in Beirut, narrow back alleys are lined with small factories, manned by young and old men. Strips of leather hang from ceilings and thick pots of glue squat next to old sewing machines. The French Open tennis final played, sound muted, in the corner when I visited.

Many of these small workshops employ Syrian workers, some through Syrian employers. One such tailor, who is amongst those several thousand Syrians and Lebanese who have been traversing back and forth between the countries for many years, pays his workers a fixed salary so that they have money even if there is no work for them. He has helped over 100 people in this manner, rotating employment to distribute wealth. He is an egalitarian, enforcing his own rules. “I help women as much as I can in the factory. I help them with some food — oil and foodstuffs. If I see they are too poor to help themselves, I help them with a salary.” These Syrians are refugees — if being expelled from their home by death and destruction is enough to qualify them for that term — but they prefer to work as migrants, and deliberately remove themselves from the protection of refugee status. (Their self-respect won’t allow that label.) Dignity is not some luxury. Its presence or absence affects the future of the refugees’ new life, however permanent — the way they bring up their children, their relationship with their new country, their new neighbors, themselves.

The international response to the refugee crisis is focused squarely on protecting refugees, not on preserving their dignity. But asserting some self-worth, some sense of control over a position of complete vulnerability, is also a need — another boundary of overlap between refugee and migrant.

¤

Refugees are not, as E.F. Kunz argued with his definitive “Kinetic Model” theory, “the movement of the billiard ball: devoid of inner direction, their path is governed by kinetic factors.”1 Rather, there now seems to be some element of choice involved, although this choice is also determined by uncontrollable circumstance. “Recognizing that mobility plays a key role in how most refugees respond to displacement is likely to prove crucial to future maintenance and functioning of the international refugee protection regime, as well as the global economy and labor market,”2 writes Professor Katy Long. The logic that refugees stay in their first country of asylum is premised on granting them full access to a decent quality of life in that country. Decent is an ambiguous word here, but one of its fulfillments might be the ability to work.

South Africa and Uganda allow refugees to work, while neighboring Botswana and Kenya prohibit employment. In Egypt bureaucratic hurdles and government hostility make practical access to the labor market extremely difficult to secure. In Europe, Serbia has an asylum system intended to create limbo — access to asylum procedure and reception conditions is limited and, once they get there, recognition rates regarding refugee status are pretty much zero. Those refugees who can do it respond by moving on and, in so doing, enter a blurred area of categorization.

In 2007 the UNHCR published a 10-page paper, “Refugee Protection and Mixed Migration: A 10-Point Plan of Action.” One of the points addressed “secondary movements” — the situation of refugees and asylum seekers who have moved on from countries where they had already found adequate protection. “To date [2007] efforts to articulate such a strategy have failed to muster international consensus.”3 To date [2015] this failure is becoming more entrenched.

Humanitarian actors insist that confusing migrants with refugees is detrimental to refugee protection. This continues to be proven across the world. Not every country is signed up to the 1951 Refugee Convention, and potential refugees are normally regarded as illegal migrants, making them susceptible to detention, expulsion, and other risks. Uighur groups, who are predominately Muslims from Xianjiang in China and accuse the Chinese government of religious and cultural repression, are a case in point. In April last year, 16 suspected “illegal migrants” thought to be Uighurs became embroiled in a fight lasting more than three hours with border guards. The bodies of those killed and the remaining “migrants” were transferred back to China, but questions were raised over the unusually fast transfer of bodies, and the swift removal of references to the Uighurs in the press. The cover-up hinted that the “migrants” were in fact refugees fleeing persecution. The case adds credence to Assistant High Commissioner for Protection at UNHCR, Erika Feller’s 2005 warning that “refugees are not migrants [...] it is dangerous, and detrimental to refugee protection, to confuse the two groups, terminologically or otherwise.”

But the issue is not one of denying the existence, or need for protection, of refugees. Rather it is one of acknowledging the complex vulnerabilities of both refugees and migrants, and how categorizing these can have a negative impact on their protection and long-term livelihood. The current European crisis won’t become any easier to manage by simply recognizing mixed migration flows. Recognition can, however, further clarify the complex nature of mobility, and the many layers of vulnerability within it. Some researchers are suggesting using labor migration to strengthen the international refugee protection regime — facilitating refugees’ movement and integrating them into labor migration programs. Whatever the outcome, it’s increasingly clear that Europe is shirking responsibility for refugees by labeling them as “migrants.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Helen Mackreath is the Middle East Correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books based in Istanbul, previously in Beirut and the West Bank. She is currently researching issues relating to Syrian refugee governance in Turkey.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Shadow City: Migrant Workers in Beirut

A culture of indentured servitude is increasingly the norm in Beirut.

At Home with Syrian Refugees and Their Hosts

New from "Around the World"

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2015%2F10%2F047.jpg)