LANGUAGE FLOWS through the work of artist Frances Stark in singular, unusual ways. In several works on paper in her current Hammer Museum retrospective she portrays herself as a bird — a peacock, a wren, a cockatoo — as in Portrait of the Artist as a Full-On Bird (2004), grasping a twig made of collaged letters; or a woodpecker, as in A Bomb (2002), about to nudge with its beak the penciled “A” in an Emily Dickinson fragment printed and repeated in the shape of a sphere. The bird analogy is fitting in many ways for an artist who flits between media, alights gently, sometimes tentatively, on ideas, and pecks through a library’s worth of books for bits of text. But the bird is also in her name: Frances Stark, starling, lark, perching on branches — and “stark” describes the spare, black-and-white aesthetic of many of her works; stark is the way she bares her person, and/or her persona. “But what of Frances Stark,” the title of a 2009 artist’s book asks, “standing by itself, a naked name, bare as a ghost to whom one would like to lend a sheet?” The perfect fit of this artist’s name is almost enough to convince you that people are language’s instruments, and not the reverse.

Portrait of the Artist as a Full-On Bird (2004)

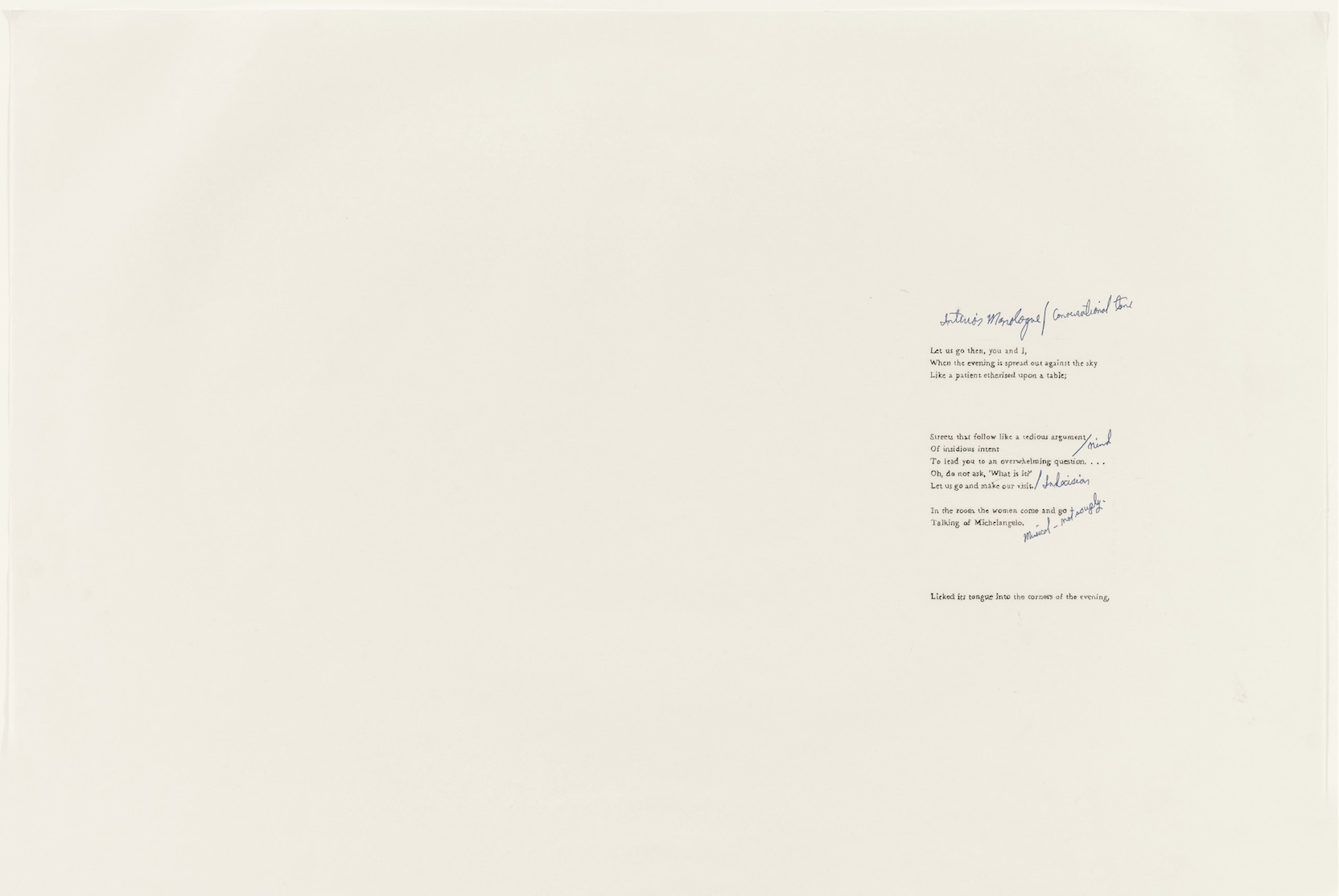

The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock (1993)

To encounter Stark’s work is to become acquainted with her home, including her studio, furniture, books, friends, breakdowns and breakthroughs, and the movement of her thought. Her earlier output involves acts of reading and copying, as if she’s pushing to understand her relation to other artists — the relation between any receiver and an artist; the relation between word and image. The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1993) blows up a used, found copy of the poem along with the notes someone scrawled in the margins: “Interior monologue/conversational tone,” the unknown reader writes in blue pen above Eliot’s “Let us go then, you and I,” coincidentally or clairvoyantly describing the very quality that will define Stark’s voice. Having an Experience (1995) is a drawing of someone’s excited underlining in John Dewey’s Art as Experience, with the original text removed, leaving only a pattern like ghostly birchbark — a print of a reader’s brain lighting up. In a series that runs from the mid-’90s to the early 2000s, she takes strings of text from her reading and repeats them across a page, as if dragging writing into a visual realm, smearing art with language.

The writers she reveres and weaves into her thinking and art — Robert Musil, Emily Dickinson, Virginia Woolf, Thomas Bernhard, Goethe, Henry Miller, and Oscar Wilde, to name several — are what Woolf calls in A Room of One’s Own the “contemplative” type as opposed to the “naturalist-novelist,” whom she deems the “less interesting branch of the species.” In other words, Romantics: the type prone to spending idle afternoons on the divan. In a 2000 catalog essay on the artist Bas Jan Ader, reprinted in her Collected Writing: 1993–2003, Stark quotes a snippet of a letter in which Musil

talks a great deal of idleness and how he writes down a quote and paces the room until the sun sets, or reads a line from a book and lies around smoking cigarettes, quietly forgetting his ideas because he didn’t write them down. Thus I often lay on my divan and slave away at this kind of self-annihilation.

“I am like Musil,” she continues, “except I don’t smoke and I never wrote a 1,700 page book of scintillating genius, but I do lie around doing nothing, self-annihilating, for not turning all my nothing into something.”

The above passage is typical of her writing, in that instead of discussing the essay’s ostensible subject, Bas Jan Ader, it circles around her process of assembling the text, and all the ways in which she becomes sidetracked from her goal. Though really, always viewing herself primarily as an artist-writer, not a critic, her true goal is to paint another’s portrait by way of painting her own, and/or vice-versa. Her texts — the catalog essays, the several artist’s books she published, her column that ran from 1999 to 2001 in the former publication art/text, and assorted contributions to other art publications and catalogs — are like pots of noodles: tangled, but often satisfying, intentionally quotidian, sometimes unfinished. They have loose structures, sculpted with a feather touch, with squiggly, unsquared edges. They snake between aimless interior monologue and precise scholarly criticism. They dance in the margins around their subject, as if too anxious or reverential to put an arrow in its heart. They are fascinated with their own collapse. They bat around ideas like cats playing for their own pleasure. “Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter,” as Wilde writes in The Picture of Dorian Gray — a novel whose universe, with its long conversations in the artist’s studio, its divan-lounging characters, enchantment with a male muse, erotic charge, melancholy, and touch of madness, seems separated from Stark’s by a thin membrane.

Along with mapping her mental landscape, Stark maps the physical rooms she paces, the roads she drives, the furniture on which she lies, the containers that hold her, and the paths that draw her along. In The Architect and the Housewife (1999) (a “book, albeit a rather petite one,” as she calls it in a 2002 essay partially titled A beholder of fragments and ruiner of plans), she describes the way her couch cuts diagonally through the room’s center, backing up against her writing desk, the walls left free for her drawings: “So you see this curious arrangement (of my couch and my desk, not my writing and my writing-drawing) is predicated on the fact that not only is my living room my living room but my living room also serves as my studio.” Uneasy about this conflation of her domestic and working life, and uneasy about her uneasiness, she proceeds to crack open a series of observations about architecture and housewifery, exterior and interior production sites, male and female artists, the studio’s boundaries.

Was I not like a housewife, toiling within the confines of my home and serving as both hostess and docent of my tiny quarters? Were [certain male friends of hers involved in large-scale art projects] not unlike architects in that they were constantly carrying out plans — giving instructions, making constructions?

In Behold Man! (2013), an expansive, prismatic self-portrait that, as Howard Singerman nicely puts it in the exhibition’s catalog, “layers looking and being looked at,” she lounges on the couch (in a different studio this time, having eventually rented a separate one in LA’s Chinatown) as she oversees her male assistant-friend-muse, Bobby Jesus, who’s reflected above her in a mirror. In Pull After “Push” (2010) she reclines before her studio windows as if comfortably absorbed in thought. In these and other images, she depicts herself and her world — almost always the inner world of her studio — as basic shapes, the couch and other furniture like coloring-book forms, a black-and-white checkerboard floor receding, outer reality entering through collage: color postcards of other artists’ paintings, junk mail, exhibition posters, fabric scraps, and bits of text in many forms.

Behold Man! (2013)

Pull After “Push” (2010)

We can see her living inside her art the way we see a character inside a novel, thinking, working, sleeping, talking, and loving within the walls of a glass house. And her art, like a house, is an extension of her body even more so than for most artists. Her self seems determined to pour itself out, into the world, into others’ minds, whether through language or image. The stakes are high. Frances Stark is a flesh-and-blood person — but she’s also a being who has made herself, and who constantly shows herself making herself, out of art and language. If her work is on the verge of collapse, on the verge of dissolving, then so is she. Much of its pathos derives from this flattening, this interweaving of artist and her work, so that to knit a stitch in one is to knit a stitch in the other. It’s the art of someone, on the one hand, with great determination to figure herself out, and, on the other, who possesses the bottomless knowledge that the self can never be figured, and that she, especially, as an artist who floats between media, and as a woman, is one who exists in a permanent state of dissonance as hopeless as it is sometimes generative and fruitful.

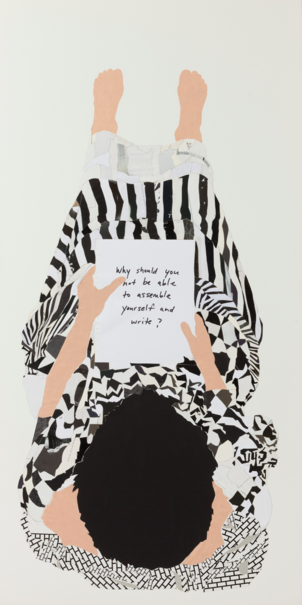

She’s also an artist who struggles with occasional creative blocks; sometime at the beginning of the 2000s, writing abandoned her. The poster image for the Hammer exhibition is a 2008 self-portrait in which she looks down on herself from above, reclining in white space on an invisible piece of furniture, perhaps the couch in her studio. She holds a paper on which is written the question: “Why should you not be able to assemble yourself and write?” Her head of dark hair is a solid shape, an ink pool, as if her words have melted or congealed, as if all thought has collapsed to image. The question originated in an email sent to her by an editor friend: “I have watched, and heard reports of your strategic maneuvers on slowly withdrawing from writing on focusing on making ‘work,’” he writes earlier in the message, whose entire text is collaged into another of her paintings, Music Stand (2008). In the self-portrait, she’s dressed in clothing made of collaged black-and-white patterns from her previous paintings — made of visual art, as if she’s assembled of that medium now, planted for good in that realm. But her posture, her solitude as she reads the words, betray her worry that writing, which has always flowed through her, has gone.

And the answer to her friend’s question? One possibility: she was busy. Her schedule had mushroomed. She had a small child. Another: writing doesn’t pay as well, not her kind of writing as compared to her kind of art. Another: writing can be a harder thing to assemble. Visual art is better at accommodating incoherence and disorganization; it doesn’t necessarily require the artist to lead the viewer along an intelligible path through time, with each word, or step, a potential point for falling off. The open-ended, anti-narrative theories of postmodernism never stuck to literature for this reason, even though many important experiments enlarged and altered the shape of the stream. And writing must often be assembled in quiet and solitude. If a desk, a horizontal plane, is for the writer, and a wall, a vertical plane, is for the artist, Stark was simply spending too much time standing up, moving around. And maybe when she wasn’t moving she was exhausted on the couch, merely resting. Her friend might as well have flipped the question: “Why should you not be able to write, and assemble yourself?”

The story of how she finally returned to writing — in a fashion, anyway — is the story of her flesh-and-blood body asserting itself, as if thrusting up through all the words her former writer-self had piled up. In one of the programs associated with the exhibition, Stark invited Alexyss K. Tylor, host of a talk show called Vagina Power, for an interview at the museum. (Interviews are another kind of portraiture/self-portraiture.) Tylor’s interpretation of Stark’s tale about overcoming her block — how she rediscovered writing unexpectedly, in the course of online sex chats — was that she had to access her lost energy from the root of herself. From there, she could rise back into her head. What emerged in the end from her seeming detour into the world of Chatroulette, where she spent hours in her studio not contemplating a painting or puzzling out a text but getting turned on by random men in far-flung cities, was, again, language — in the form of typed phrases on the screen that seemed throwaway, but wove themselves into narratives and unintentional scraps of poetry. This continued until her resonant, funny film, brilliantly titled My Best Thing after one of her remote paramours’ nicknames for his penis, and featuring animated characters made for free with online software called Xtranormal, appeared as an idea and grew into being.

Why should you not be able to assemble yourself and write? (2008)

My Best Thing (2011)

Bobby Jesus’s Alma Mater b/w Reading the Book of David and/or Paying Attention Is Free (2013)

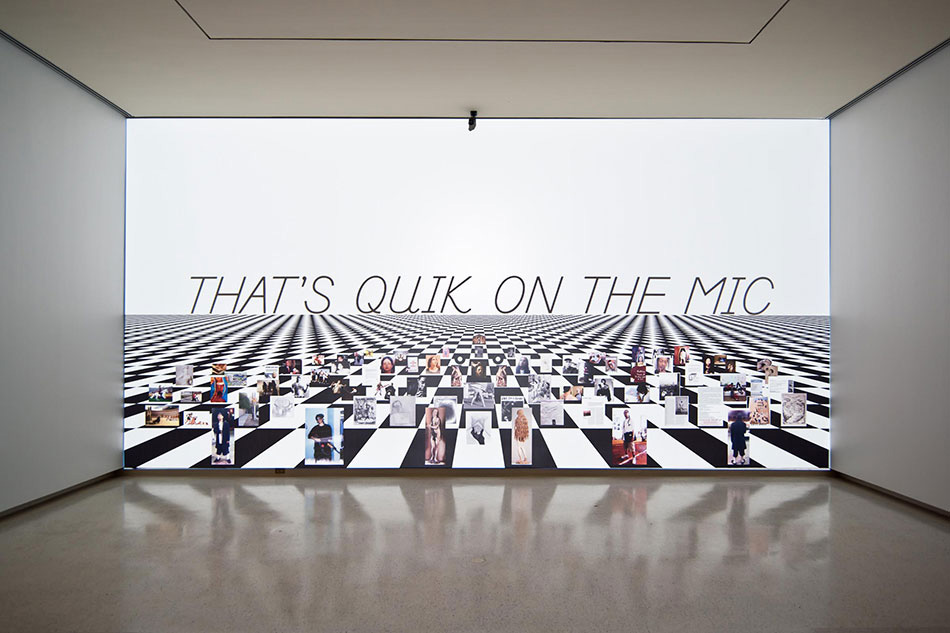

Since her breakthrough, the tone of Stark’s work has changed. Whereas in her early work she tends to examine the margins, in her later work she puts herself center stage. If before she tended to identify with the housewife side of her housewife/architect binary, she now seems more like the architect, “a figure who carries out big plans on a large scale, and in actual space,” as she has it in the 2002 A beholder of fragments essay. Bobby Jesus’s Alma Mater b/w Reading the Book of David and/or Paying Attention Is Free (2013), a multichannel projection with music by DJ Quik, one of her objects of obsession, has her text flashing in giant bold letters above a floor made of black-and-white tile. “I’m a holy whore, players, hear me out,” a line pulses. “That gun in my mouth, I’m taking it out, dicks will come in, truth will come out.”

It’s the voice not only of an artist who’s entered a new phase, but who’s frustrated with the sound of a woman’s work landing in the culture: something like a sheet of paper drifting to the ground rather than a satisfying thud. Dissonance exists between the categories of “artist” and “woman” — categories which the culture conceives as distinct — as it perceives “person” and “woman” to be distinct, so that to be completely, simultaneously successful at one and the other is not quite possible. The pinnacle of existence for an artist, and person, is to be a genius, but the pinnacle of existence for a woman is — to borrow the phrase from an early Frances Stark work with an unwieldy title (How does one sustain the belief in total babes, (power/recognition) which has been recognized for its debilitating effects on that person who lacks the total babe (embodiment of power/recognition) and access to the total babe by means of one’s own total foxiness/power) — to be a Total Babe.

Assembling oneself, creating a self that is unified and that coheres, is difficult enough for anybody — perhaps more difficult for artists, and for female artists, maybe practically futile. Dissonance could even be a quality expressing itself in part through the experience of women, for all anyone knows. The painter Laura Owens, who appears as a character in The Architect and the Housewife and with whom Stark discussed ideas contained in the title (“[…] we began to consider whether ‘interiority’ and ‘exteriority’ were types of meaning-production as well, interiority evoking more of a Romantic tradition and exteriority being perhaps more in line with the avant-garde. Maybe, maybe not […]”), said the following in an interview in Artforum with Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer, on the occasion of her 2013 inaugural exhibition at her 356 Mission gallery:

“I had asked myself, in a depressed mood: Is it even possible for a woman artist to be the one who marks? […] Isn’t it interesting that a male orgasm has a DNA imprint that will replicate itself over and over again, reinforcing itself the way language or naming might, but the female orgasm has no use, no mark, no locatability? It can’t even be located in time. […] I want to think about how that can be the model for a new gesture. What is that gesture in art, or in painting?”

Along with her career-spanning investigations into the nature of art and language and their interrelations, Stark is among the artists searching out this kind of new gesture, drilling straight down into the still largely unexamined, rarefied cultural zone where “woman” and “important artist” overlap, into the heart of dissonance, and finding its essential pulse.

¤

Katherine Satorius is a writer and editor based in Los Angeles whose art writing and fiction(much of it archived here) have appeared in MAKZine, ZYZZYVA, ArtUS, DIAGRAM, and others. She is completing a novel.

LARB Contributor

Katherine Satorius is a writer and editor based in Los Angeles whose art writing (much of it archived here [ksatorius.wordpress.com]) and fiction have appeared in MAKZine, ZYZZYVA, ArtUS, DIAGRAM, and others. She is completing a novel.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Broad Appeal: The Gateway Museum

The Broad is like a gateway drug.

A Deep but Unstable Joy: Gazing at Agnes Martin

A much-repeated idea about a Martin painting is that it isn’t reproducible in print.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2016%2F01%2F2013-2-Bobby-Jesuss-Alma-Mater...._Brian-Conley-copy.jpg)