All photographs courtesy of David Shaw. All rights reserved.

“It wasn’t always the plan to stay in London.”

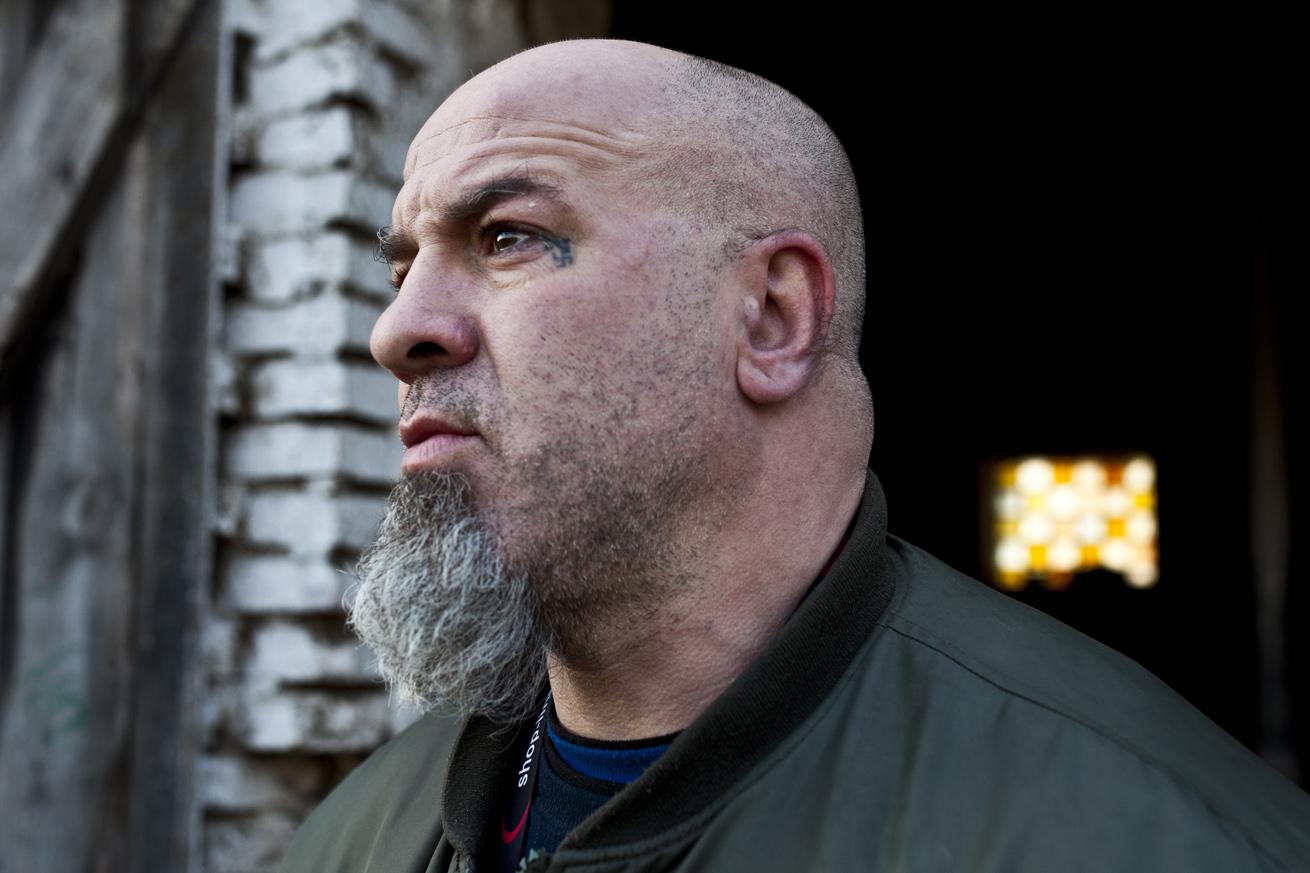

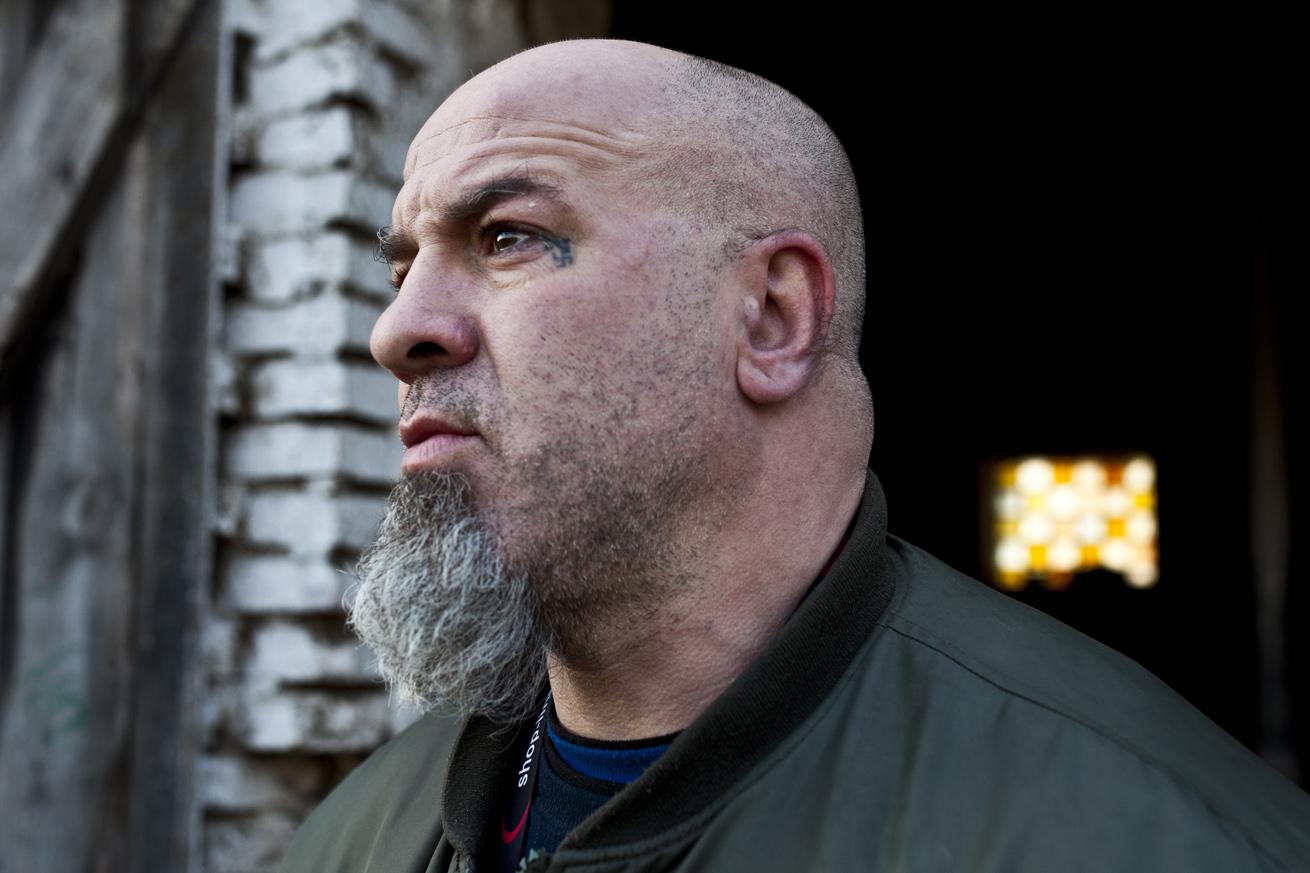

JERZY “THE SAILOR” was 54 when he first came to London to visit his son, who was working there at the time; it was supposed to be a quick visit just to see his family. An alcoholic, he lived in Poland working “unofficial” odd jobs on construction sites, making just enough to maintain his drinking habit. During his visit to London, he saw the opportunity to get a more secure job and take some money home.

Jerzy’s new plan was to earn enough money to move to the coast in Poland and find a job as a sailor or a ship’s mechanic, which had been his “true” profession in the old days of communism — in the time of the Polish People’s Republic. Back then, Jerzy worked in a state cooperative as a sailor on a Barka ship, a long boat used for the transition of people and materials along the rivers. He was a sailor for most of his life professionally. In the old communist system, a worker would be trained in one job and then would work this job for the rest of his or her life. He didn’t have to be the best at it, he just had to do his part and then the system (government) provided for the rest: healthcare, education, and other social services. When the country transitioned to a free market system, Jerzy, and a whole generation of people like him, were unable to adapt to a world where everyone was no longer guaranteed a job. With a free market system, state industries, such as mining, shipyards, and factories, were privatized, and many others, including Barka, went bankrupt. Millions of people, including Jerzy, lost their jobs.

Jerzy got a new “black money” construction job in London and was earning enough to return to Poland to get his “dream job.” For three months, he lived with his son and was sober, but couldn’t maintain it. He slipped back into drinking, had an argument with his son, and left.

“After the third bar, I had lost all my baggage, and after a week, I woke up on the streets with no money.” He could not remember a thing.

He was living on the streets of London, sleeping in a cemetery, where foxes woke him at night by biting his legs. Eventually, he ran into a man he’d met before, called “bin Laden” (due to his big beard). During better times, he’d helped bin Laden with money and food. Bin Laden took Jerzy in to his self-made home in Fulham on the edge of the River Thames.

Jerzy continued working illegally as a construction worker, joining a black market Polish labor community competing for the same jobs. Every day they gathered at a place in Hammersmith for building site managers to pick them up. There was a solidarity rule among the workers that they would not work for less than 50 pounds a day so as to keep everyone’s wages higher. Anyone who worked for less? “The other guys would kick his ass.”

Jerzy lived this way for a time until one day bin Laden stabbed a man with an old bayonet for trying to take his home. He was quickly arrested and imprisoned. Jerzy was back on the street again, desperate and alone.

He soon discovered that a new organization called the Barka Foundation was offering employment and social services to migrant Polish workers in situations like his. The Foundation goes so far as to bring the migrants back to Poland, and helps resettle them there. These “Barka communities” comprise a new movement taking hold in Poland, and worldwide. They are a new form of social cooperative created to not only help the people already left behind in Poland’s new society, but also to address the social conditions, such as unemployment, low wages, and lack of healthcare, that compel people to emigrate in the first place.

Today, Jerzy, 63, works in Ireland, helping people in similar situations to his, supporting homeless Eastern and Central Europeans.

A Collective Place

In Poland today, a lack of new small businesses means no one is offering jobs. This is due in part to a tough bureaucracy that includes draconian tax laws on small businesses, but also because of the transition to a free market. During communism, the state frowned upon residents trying to start their own businesses, as it was seen as working for oneself rather than for the state; this attitude is still prevalent in Poland today.

Social cooperatives are an innovative way of addressing this psychology while also providing a means for generating economic activity through grassroots organizing. This network of co-ops was first pioneered by the Barka Foundation, or The Barka Foundation for Mutual Help, which created self-sustainable communities that also work as social reintegration centers for Polish people living in poverty. The model has been so successful that it has quickly spread across Poland and abroad to places as far as Kenya.

The co-op members live and work together in these communities as they regain a footing in their lives. For the many Polish who immigrated to the EU thinking life would be easier but found it wasn’t, Barka has a network of contacts throughout Europe, offering them a chance to come home and live in one of their residential cooperatives/communities. These communities give the migrants a chance to get healthy, learn new skills, and generally gain new self-worth through support and an occupation.

The Village of Skinny Dogs

Tomac, 37, is the leader of the Chudobcyce (Skinny Dogs) village cooperative. It houses about 80 members on the site of an old soviet farm. The co-op has a range of activities, including a social reintegration center, mainly for ex-prisoners. Its main activity is the running of the farm. The co-op has become so successful under Tomac’s leadership that it is financially self-sufficient, which is why Tomac keeps the member count at 80 rather than accepting more.

Tomac himself used to be a gangster. He was in and out of correctional facilities from a very early age; criminal behavior ran in the family. He turned his life around with the help of Barka and now lives in Chudobcyce with his wife and two children. He often talks about Polish prisons, about his experiences there and eventual reformation. He has become a role model to prisoners throughout the country, which is why Barka gave him the responsibility of running the co-op.

Many people working at the co-op come from local prisons, such as Christopher, a nice yet intimidating looking man who came to the farm after deciding to change his life. Work starts at six a.m.; they keep many different livestock such as sheep, cows, pigs, and goats.

Heslaw, 60, found the co-op after losing a long career working on the trains due to a recession; he says he “loves the farmwork.”

Another member, Mariouz, 40, lived and worked in Dublin for many years after moving there illegally in 1994 and working under-the-table jobs. He was able to work on Irish fishing trawlers after Poland joined the EU. When asked if he enjoyed his time in Dublin, he gruffly replies, “Yeah, it was a good craic, plenty women.” Due to both of his parents being ill, Mariouz had to return to Poland, only to find he was unfamiliar with many elements of the new Polish society, including how to get a job. Luckily, as he has good mechanical skills, he was offered a place at the co-op, and now he lives and works at the farm.

“It’s a different craic, a different setup. People respect themselves here and respect the place.”

A 20 minute drive away is the Wielkopomoc (Great Support) Association Co-Operative in the tiny village of Posadowek. This co-op is a much smaller operation of about 25 members, but runs with the same ideals and goals as the farm. Wielkopomoc runs a shelter and resettlement center for homeless dogs, and it also acts a reintegration home.

The members seem a lot closer to one another here, perhaps due to the co-op’s smaller, more intimate size. Joanna Monika, 36, is the co-op’s cook and only woman. She says that “we are a family, we fight, we talk, we love, and we live together.”

Joanna has lived at the co-op for two years. Her arrival was an escape from her alcoholic and violent husband, a wealthy man with whom she lived in Poznań. She too had a stable and lucrative job as an accountant; their lives were, on the surface, secure. The victim of ongoing and severe physical and emotional abuse, she left it behind for the co-op.

“It is okay now, I learn English and I meet people, many different people, people who were on the street, people who had problems with alcohol even more than me […] also I love the dogs, this is a happy place for me.”

Many co-op residents are recovering alcoholics — especially those of an older generation that grew up under communism, or those individuals who have returned after emigrating. There is a strict prohibition against drinking on the co-op grounds, so sometimes people will leave for a few days to relapse.

“Once one guy went on a fishing trip. He disappeared for four days,” Joanna says.

Members are all given small living quarters on the site of the dog shelter. They eat communally; the co-op provides all the food, and one or two of the members will work in the kitchen. The co-ops are run on an equality basis, with all wages being the same, even if an individual cannot find work; everyone takes on responsibilities within the organization. They are also supported by local authorities, which give financial help to many of the groups.

Lukasz, 25, used to live in Manchester, United Kingdom. He went there to work for one year when he couldn’t find employment in Poland.

He worked legally in shops and on building sites in Manchester, but eventually moved on to Amsterdam in Holland because it was better money and closer to home. After four years however, Lukasz found himself on the streets.

“I was on the streets for only one month, but this was enough. I am going to say it honestly, it was because of drugs. I lost everything because of drugs and I am not ashamed [to tell you] as it is only true.”

He used for four years until he was eventually fired after being caught with drugs on the job (for the third, and last, time). Two months later, he lost his flat as he could not pay his bills. After living on the streets for a month, a friend told him about Barka. When he arrived at the Wielkopomoc co-op, he was determined to get clean. Lukasz has been living at the co-op for seven months, mainly doing construction jobs, and is much happier. He is working on mending his relationship with his family, and working on returning to Holland soon.

“Living on the streets has given me a tough lesson I can say. I will never go back to it. The worst experience is how you can lose everything so fast, just like that.”

Joanna once had thoughts of starting a co-op of her own, but the onerous bureaucratic process for doing so discourages her. While the state does provide financial support for many of the cooperatives, it is still difficult to start one. Hieronin, 36, the leader at the Wielkopomoc cooperative who created the dog shelter, talks of the difficult legal processes required for keeping the co-op legally viable. Similarly, Kamila Chwalisz, one of five women who run a local children’s nursery, says that co-op members can currently only pay themselves a quarter of their usual salary. These women were once unemployed but felt that they were “not afraid of working. We have hands, we are healthy.”

Despite the difficulties, the co-ops have been and continue to be successful. For members, they are a second chance at life.

Poland Today

Professor Krystyna Iglicka-Okólska is a professor of economic sciences and rector at Lazarski University. Iglicka-Okólska believes Poland is mired in a difficult financial cycle that is largely responsible for migration, and thus, a brain drain, with highly educated people moving away in droves as jobs are rare and salaries low. One of her friends, another academic with a PhD, left her career and took her family of five to the United Kingdom, where she now works night shifts at a supermarket. The work is hard, but the money steady; this is the choice many Polish people have to make.

Izabela Grabowska-Lusinska, the head of the Research Unit at the Centre of Migration Research at the University of Warsaw, says that many people in Poland are “sick for normalcy.” This is particularly present with young people looking to start families who are attracted to the state support and education available to them abroad; it gives them more of a safety financially that they can’t get in Poland. That, and a better lifestyle: in Poland, it is common to work very long hours with no breaks. Only nine percent of Polish people in the United Kingdom have high-skilled jobs, but they are attracted to opportunities for a better life, like holidays to Spain, and an easy-to-gain mortgage.

Halina Leczycka, 62, lives in a small post-communist apartment in the far eastern Polish town of Bielsk Podlaski. Her daughter, Izabella, is 36 and has lived in Dublin since 2006. She and Izabella see each other two or three times a year; however, they keep in contact over Skype at least once a week. Izabella left for Dublin with her husband in the hopes that a new life would help them repair their marriage. However, it didn’t, and she has stayed in Dublin as a single woman since they broke up.

Izabella’s sister was already in Dublin, and often talked about how good and different life was there. This eventually persuaded Izabella to move there. Her sister currently lives in Kraków in Poland but is aiming to move to London.

Helina says that Izabella left mainly because of local attitudes and mentality.

“In Poland, everyone is stressed in work and in their life, and she didn’t want to live that way.”

Family Life

These migration patterns have hit Polish family life hard. Grazyna Noskowicz has been in Beilsk Podlaski alone, as her two children moved elsewhere in the EU for work after her husband died. She is happy that “they have more money, and have no worries about money or security.” However, she suffers without them and her grandchildren, and desperately wants them to come home.

“There is nothing for them to come back to. The social security is okay and they feel safe. Young and ambitious people will go abroad. It is about work and the money and there is not enough opportunity here.”

For Polish people who successfully emigrate, the rewards can be great. Cerzary Lubowicki went to live in Ireland after his sister moved there three years earlier. She has started a family there and now has two daughters.

“Like everyone, we went for money. Poland in 2004 was not the bright country that it is now, and you could only get terrible wages. Like every Polish guy, I am thinking about it [leaving], maybe [for me] not for money but for travel and adventure. At my age everyone [in Poland] is either thinking about it, or is abroad.”

Cerzary’s sister has done so well as a beautician in Dublin that she has built a three-story home for her family back in Poland. It is far away from the communist-style residential blocks across the street — a perfect example of how migration can bring prosperity to individuals and families. Still, it is hard to get the family back together.

“We could try and have our lives here, but it is taxes and everything like this that stops us. You don’t leave the family for fun, you go to get your children to study, your wife some nice shoes and clothes, and a car, just normal things that you have in the West. Here, it’s going better, you can see three cars in people’s front yards, they are used and from Germany, but it’s going to get better.”

Outside his sister’s newly built house, Cerzary proudly stated that she built it with her own money, not “Irish money.”

Many, especially the older generation under communist rule, have been left behind in today’s Poland. Meanwhile, the younger generation are seeking a better life. Everyone hears from their friends and relatives about the new lives awaiting them abroad.

Despite this, the social cooperative movement has created a new way for people to reconnect with a better, Polish way of life. For others like Cerzary, who have left and succeeded in creating a better life for themselves, Poland is a country still lost in the shadow of history.

“I feel like people from the West still see us as Eastern European. I meet people from the West and they are very nice, but sometimes they treat us differently. There is the syndrome we carry.”

* This work was made possible with support from the Peter Kirk Scholarship.

David Shaw is a photographer and journalist from the United Kingdom. He specializes in investigative reportage, creating in-depth photo essays and articles focusing on human rights, social issues, and other human interest stories.

¤

“It wasn’t always the plan to stay in London.”

JERZY “THE SAILOR” was 54 when he first came to London to visit his son, who was working there at the time; it was supposed to be a quick visit just to see his family. An alcoholic, he lived in Poland working “unofficial” odd jobs on construction sites, making just enough to maintain his drinking habit. During his visit to London, he saw the opportunity to get a more secure job and take some money home.

Jerzy’s new plan was to earn enough money to move to the coast in Poland and find a job as a sailor or a ship’s mechanic, which had been his “true” profession in the old days of communism — in the time of the Polish People’s Republic. Back then, Jerzy worked in a state cooperative as a sailor on a Barka ship, a long boat used for the transition of people and materials along the rivers. He was a sailor for most of his life professionally. In the old communist system, a worker would be trained in one job and then would work this job for the rest of his or her life. He didn’t have to be the best at it, he just had to do his part and then the system (government) provided for the rest: healthcare, education, and other social services. When the country transitioned to a free market system, Jerzy, and a whole generation of people like him, were unable to adapt to a world where everyone was no longer guaranteed a job. With a free market system, state industries, such as mining, shipyards, and factories, were privatized, and many others, including Barka, went bankrupt. Millions of people, including Jerzy, lost their jobs.

Jerzy got a new “black money” construction job in London and was earning enough to return to Poland to get his “dream job.” For three months, he lived with his son and was sober, but couldn’t maintain it. He slipped back into drinking, had an argument with his son, and left.

“After the third bar, I had lost all my baggage, and after a week, I woke up on the streets with no money.” He could not remember a thing.

He was living on the streets of London, sleeping in a cemetery, where foxes woke him at night by biting his legs. Eventually, he ran into a man he’d met before, called “bin Laden” (due to his big beard). During better times, he’d helped bin Laden with money and food. Bin Laden took Jerzy in to his self-made home in Fulham on the edge of the River Thames.

Jerzy continued working illegally as a construction worker, joining a black market Polish labor community competing for the same jobs. Every day they gathered at a place in Hammersmith for building site managers to pick them up. There was a solidarity rule among the workers that they would not work for less than 50 pounds a day so as to keep everyone’s wages higher. Anyone who worked for less? “The other guys would kick his ass.”

Jerzy lived this way for a time until one day bin Laden stabbed a man with an old bayonet for trying to take his home. He was quickly arrested and imprisoned. Jerzy was back on the street again, desperate and alone.

He soon discovered that a new organization called the Barka Foundation was offering employment and social services to migrant Polish workers in situations like his. The Foundation goes so far as to bring the migrants back to Poland, and helps resettle them there. These “Barka communities” comprise a new movement taking hold in Poland, and worldwide. They are a new form of social cooperative created to not only help the people already left behind in Poland’s new society, but also to address the social conditions, such as unemployment, low wages, and lack of healthcare, that compel people to emigrate in the first place.

Today, Jerzy, 63, works in Ireland, helping people in similar situations to his, supporting homeless Eastern and Central Europeans.

A Collective Place

In Poland today, a lack of new small businesses means no one is offering jobs. This is due in part to a tough bureaucracy that includes draconian tax laws on small businesses, but also because of the transition to a free market. During communism, the state frowned upon residents trying to start their own businesses, as it was seen as working for oneself rather than for the state; this attitude is still prevalent in Poland today.

Social cooperatives are an innovative way of addressing this psychology while also providing a means for generating economic activity through grassroots organizing. This network of co-ops was first pioneered by the Barka Foundation, or The Barka Foundation for Mutual Help, which created self-sustainable communities that also work as social reintegration centers for Polish people living in poverty. The model has been so successful that it has quickly spread across Poland and abroad to places as far as Kenya.

The co-op members live and work together in these communities as they regain a footing in their lives. For the many Polish who immigrated to the EU thinking life would be easier but found it wasn’t, Barka has a network of contacts throughout Europe, offering them a chance to come home and live in one of their residential cooperatives/communities. These communities give the migrants a chance to get healthy, learn new skills, and generally gain new self-worth through support and an occupation.

The Village of Skinny Dogs

Tomac, 37, is the leader of the Chudobcyce (Skinny Dogs) village cooperative. It houses about 80 members on the site of an old soviet farm. The co-op has a range of activities, including a social reintegration center, mainly for ex-prisoners. Its main activity is the running of the farm. The co-op has become so successful under Tomac’s leadership that it is financially self-sufficient, which is why Tomac keeps the member count at 80 rather than accepting more.

Tomac himself used to be a gangster. He was in and out of correctional facilities from a very early age; criminal behavior ran in the family. He turned his life around with the help of Barka and now lives in Chudobcyce with his wife and two children. He often talks about Polish prisons, about his experiences there and eventual reformation. He has become a role model to prisoners throughout the country, which is why Barka gave him the responsibility of running the co-op.

Many people working at the co-op come from local prisons, such as Christopher, a nice yet intimidating looking man who came to the farm after deciding to change his life. Work starts at six a.m.; they keep many different livestock such as sheep, cows, pigs, and goats.

Heslaw, 60, found the co-op after losing a long career working on the trains due to a recession; he says he “loves the farmwork.”

Another member, Mariouz, 40, lived and worked in Dublin for many years after moving there illegally in 1994 and working under-the-table jobs. He was able to work on Irish fishing trawlers after Poland joined the EU. When asked if he enjoyed his time in Dublin, he gruffly replies, “Yeah, it was a good craic, plenty women.” Due to both of his parents being ill, Mariouz had to return to Poland, only to find he was unfamiliar with many elements of the new Polish society, including how to get a job. Luckily, as he has good mechanical skills, he was offered a place at the co-op, and now he lives and works at the farm.

“It’s a different craic, a different setup. People respect themselves here and respect the place.”

A 20 minute drive away is the Wielkopomoc (Great Support) Association Co-Operative in the tiny village of Posadowek. This co-op is a much smaller operation of about 25 members, but runs with the same ideals and goals as the farm. Wielkopomoc runs a shelter and resettlement center for homeless dogs, and it also acts a reintegration home.

The members seem a lot closer to one another here, perhaps due to the co-op’s smaller, more intimate size. Joanna Monika, 36, is the co-op’s cook and only woman. She says that “we are a family, we fight, we talk, we love, and we live together.”

Joanna has lived at the co-op for two years. Her arrival was an escape from her alcoholic and violent husband, a wealthy man with whom she lived in Poznań. She too had a stable and lucrative job as an accountant; their lives were, on the surface, secure. The victim of ongoing and severe physical and emotional abuse, she left it behind for the co-op.

“It is okay now, I learn English and I meet people, many different people, people who were on the street, people who had problems with alcohol even more than me […] also I love the dogs, this is a happy place for me.”

Many co-op residents are recovering alcoholics — especially those of an older generation that grew up under communism, or those individuals who have returned after emigrating. There is a strict prohibition against drinking on the co-op grounds, so sometimes people will leave for a few days to relapse.

“Once one guy went on a fishing trip. He disappeared for four days,” Joanna says.

Members are all given small living quarters on the site of the dog shelter. They eat communally; the co-op provides all the food, and one or two of the members will work in the kitchen. The co-ops are run on an equality basis, with all wages being the same, even if an individual cannot find work; everyone takes on responsibilities within the organization. They are also supported by local authorities, which give financial help to many of the groups.

Lukasz, 25, used to live in Manchester, United Kingdom. He went there to work for one year when he couldn’t find employment in Poland.

He worked legally in shops and on building sites in Manchester, but eventually moved on to Amsterdam in Holland because it was better money and closer to home. After four years however, Lukasz found himself on the streets.

“I was on the streets for only one month, but this was enough. I am going to say it honestly, it was because of drugs. I lost everything because of drugs and I am not ashamed [to tell you] as it is only true.”

He used for four years until he was eventually fired after being caught with drugs on the job (for the third, and last, time). Two months later, he lost his flat as he could not pay his bills. After living on the streets for a month, a friend told him about Barka. When he arrived at the Wielkopomoc co-op, he was determined to get clean. Lukasz has been living at the co-op for seven months, mainly doing construction jobs, and is much happier. He is working on mending his relationship with his family, and working on returning to Holland soon.

“Living on the streets has given me a tough lesson I can say. I will never go back to it. The worst experience is how you can lose everything so fast, just like that.”

Joanna once had thoughts of starting a co-op of her own, but the onerous bureaucratic process for doing so discourages her. While the state does provide financial support for many of the cooperatives, it is still difficult to start one. Hieronin, 36, the leader at the Wielkopomoc cooperative who created the dog shelter, talks of the difficult legal processes required for keeping the co-op legally viable. Similarly, Kamila Chwalisz, one of five women who run a local children’s nursery, says that co-op members can currently only pay themselves a quarter of their usual salary. These women were once unemployed but felt that they were “not afraid of working. We have hands, we are healthy.”

Despite the difficulties, the co-ops have been and continue to be successful. For members, they are a second chance at life.

Poland Today

Professor Krystyna Iglicka-Okólska is a professor of economic sciences and rector at Lazarski University. Iglicka-Okólska believes Poland is mired in a difficult financial cycle that is largely responsible for migration, and thus, a brain drain, with highly educated people moving away in droves as jobs are rare and salaries low. One of her friends, another academic with a PhD, left her career and took her family of five to the United Kingdom, where she now works night shifts at a supermarket. The work is hard, but the money steady; this is the choice many Polish people have to make.

Izabela Grabowska-Lusinska, the head of the Research Unit at the Centre of Migration Research at the University of Warsaw, says that many people in Poland are “sick for normalcy.” This is particularly present with young people looking to start families who are attracted to the state support and education available to them abroad; it gives them more of a safety financially that they can’t get in Poland. That, and a better lifestyle: in Poland, it is common to work very long hours with no breaks. Only nine percent of Polish people in the United Kingdom have high-skilled jobs, but they are attracted to opportunities for a better life, like holidays to Spain, and an easy-to-gain mortgage.

Halina Leczycka, 62, lives in a small post-communist apartment in the far eastern Polish town of Bielsk Podlaski. Her daughter, Izabella, is 36 and has lived in Dublin since 2006. She and Izabella see each other two or three times a year; however, they keep in contact over Skype at least once a week. Izabella left for Dublin with her husband in the hopes that a new life would help them repair their marriage. However, it didn’t, and she has stayed in Dublin as a single woman since they broke up.

Izabella’s sister was already in Dublin, and often talked about how good and different life was there. This eventually persuaded Izabella to move there. Her sister currently lives in Kraków in Poland but is aiming to move to London.

Helina says that Izabella left mainly because of local attitudes and mentality.

“In Poland, everyone is stressed in work and in their life, and she didn’t want to live that way.”

Family Life

These migration patterns have hit Polish family life hard. Grazyna Noskowicz has been in Beilsk Podlaski alone, as her two children moved elsewhere in the EU for work after her husband died. She is happy that “they have more money, and have no worries about money or security.” However, she suffers without them and her grandchildren, and desperately wants them to come home.

“There is nothing for them to come back to. The social security is okay and they feel safe. Young and ambitious people will go abroad. It is about work and the money and there is not enough opportunity here.”

For Polish people who successfully emigrate, the rewards can be great. Cerzary Lubowicki went to live in Ireland after his sister moved there three years earlier. She has started a family there and now has two daughters.

“Like everyone, we went for money. Poland in 2004 was not the bright country that it is now, and you could only get terrible wages. Like every Polish guy, I am thinking about it [leaving], maybe [for me] not for money but for travel and adventure. At my age everyone [in Poland] is either thinking about it, or is abroad.”

Cerzary’s sister has done so well as a beautician in Dublin that she has built a three-story home for her family back in Poland. It is far away from the communist-style residential blocks across the street — a perfect example of how migration can bring prosperity to individuals and families. Still, it is hard to get the family back together.

“We could try and have our lives here, but it is taxes and everything like this that stops us. You don’t leave the family for fun, you go to get your children to study, your wife some nice shoes and clothes, and a car, just normal things that you have in the West. Here, it’s going better, you can see three cars in people’s front yards, they are used and from Germany, but it’s going to get better.”

Outside his sister’s newly built house, Cerzary proudly stated that she built it with her own money, not “Irish money.”

Many, especially the older generation under communist rule, have been left behind in today’s Poland. Meanwhile, the younger generation are seeking a better life. Everyone hears from their friends and relatives about the new lives awaiting them abroad.

Despite this, the social cooperative movement has created a new way for people to reconnect with a better, Polish way of life. For others like Cerzary, who have left and succeeded in creating a better life for themselves, Poland is a country still lost in the shadow of history.

“I feel like people from the West still see us as Eastern European. I meet people from the West and they are very nice, but sometimes they treat us differently. There is the syndrome we carry.”

* This work was made possible with support from the Peter Kirk Scholarship.

¤

David Shaw is a photographer and journalist from the United Kingdom. He specializes in investigative reportage, creating in-depth photo essays and articles focusing on human rights, social issues, and other human interest stories.

LARB Contributor

David Shaw is a photographer and journalist from the United Kingdom. He specializes in investigative reportage, creating in-depth photo essays and articles focusing on human rights, social issues, and other human interest stories. His work has taken him around the world to places such as Gaza, Lebanon, India, Nepal, Egypt, and Greece. Shaw also completes assignments for NGOs and continues to investigate important unreported stories with the goal of informing an audience through visual and written journalism.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Shadow City: Migrant Workers in Beirut

A culture of indentured servitude is increasingly the norm in Beirut.

We Remain: Polin, Museum of the History of Polish Jews

We all miss Poland and we all long to return — although not in the same way that we want to return to Israel. For most Jews, Poland remains a...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2015%2F07%2F09.jpg)