The following is a feature article from the upcoming LARB Quarterly Journal: Spring 2016 edition. Become a member of the Los Angeles Review of Books to receive your copy of the Journal.

ALL FLESH is as the grass. This dour wisdom from the Book of Isaiah is also true in reverse: all plants are as flesh. Crops of the fields, like the humans who tend them, have their day and die.

For 70 years, the defining “grass” of Orange County was its namesake product: the sweet fruit that hung from relentless furrows of trees serrating the county from top to bottom. A group of well-off Protestant migrants from the Midwest tried to bring small-farm values to new 19th-century business with the size — and a dose of the heartlessness — of a Southern rice plantation. They managed to create an economy unlike any other in America, as well as a vast tablecloth of waxy leaves, windmills, and dirt farm lanes, all cloaked on chilly mornings in a man-made, frost-defying haze of oily smoke.

The citrus trees left long shadows. Orange County’s modern-day fetish for large tracts of single-family homes, the exploitation of Latinos as laborers, the decentered urban carpet, the bland mass culture, the self-conscious expression “California dream,” the thirst for youth and cosmetics, the Iowa-like probity: all of these local distinctions can be traced to the time between 1870 and 1950 when the orange was monocultured king, and the local economy arranged around it.

A first irony: oranges aren’t native to California. The sweet variety called mandarin emerged in China and Vietnam around the time of Confucius in 500 BCE, then crossed with a related fruit called pomelo. Jews used a hard and sour breed called citron for rituals in the Feast of Tabernacles; the Moors of North Africa are thought to have brought it in the eighth century to Spain, where it softened and sweetened through hybrid speciation to something resembling the Valencias and Washington navels we eat today. During the 15th century, scurvy-wary Spanish sailors brought these seedlings to what is now California, and small groves of sweet oranges were planted on the grounds of the missions that Junípero Serra created in his path up the coast.

But the local birthplace of Orange County’s signature business is less picturesque and not even in the county: it’s a lonely stretch of Alameda Street south of Fourth Street, at the scruffy edge of downtown Los Angeles, where the only landmarks today are a row of cold-storage seafood warehouses, a weeded-over set of railroad tracks, and a liquor distribution warehouse. No plaque marks the spot where an Anglo trader planted the first set of orange trees for a commercial purpose in Southern California.

That man was William Wolfskill, a Kentucky native who had drifted to Mexico as a mountain man and gotten involved in the frontier liquor business. He and a partner sold jugs of grain alcohol mixed with red pepper and a dash of gunpowder under the name “Taos Lightning” — a booze so vile it could “peel the hide off a Gila Monster,” in the words of historian Marshall Trimble. Wolfskill married his way into Mexican citizenship, and while passing through the dusty village of Los Angeles on the way to blaze a trail to the Pacific from Santa Fe, figured that Southern California’s climate would support a citrus trade.

He acquired seeds from Serra’s 35 trees that grew near the Mission San Gabriel Arcángel and planted them near his farmhouse. There he grew rich exporting his juicy food up the coast by horse cart to the gold-rush camps near Sacramento. By the time of his death in 1866, he owned two-thirds of the orange trees in the state.

Wolfskill’s son and business heir Joseph thought even bigger. He understood that local markets were never the future of the California orange; the real money lay in shipping them to places where the fruit was an exotic species, a subject of rumor and fascination. Such was the intention of the first railroad shipment of oranges to St. Louis in 1877, in a single boxcar stacked high with crates stamped “Wolfskill California oranges.” In the lore of the California citrus trade, this was like the voyage of the Discovery, because new technology was about to make orange growers fantastically rich.

The ice-bunker car, which kept oranges cool with air blown over ice, debuted on the nation’s railroad tracks in 1889 — the same year the California Legislature approved the formation of Orange County as a separate political entity, and both the Southern Pacific and the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe feverishly extended their tendrils down to the brand-new farming boomtowns of Anaheim, Orange, and Santa Ana where the land was flat and gloriously empty. Huge fortunes could suddenly be made railing oranges east for customers eager to taste this high-priced exotic dessert.

The Southern Pacific Railroad also doubled-down on hype, popularizing the slogan “Oranges for Health, California for Wealth” and sending promotional trains to state fairs across the Midwest featuring traveling lecturers, glowing booklets, and free samples for locals to enjoy. Unlike heartland cash commodities such as wheat, corn, or oats — nutrient-dense but visually humble grasses — the California orange had an erotic maternal shape, and origins in the sun-splashed Mediterranean instead of gloomy steppes. Citrus sales doubled across the Midwest over the next decade, and some of the new consumers were persuaded to try out the California ranching dream for themselves.

These enterprising landowners tended to be Protestant, wealthy, middle-Western and middle-aged, and looking for a reinvention in the warm sun of a far land. This was, in the words of local antiquarian Charles Fletcher Lummis, “the least heroic migration in history, but the most judicious […]. [I]nstead of gophering for gold, they planted gold.”

The first job of a gentleman orange farmer was finding porous alluvial soil and nearby mountain ranges to provide shelter from restless Santa Ana winds. The best places were known to be immediately southwest of hill slopes, parallel to the wind and resistant to the “frost pockets” of stagnant cold air that could freeze the fruit off a tree in a single night. To best catch the sun’s rays, orange seedlings were planted 26 feet apart, in militaristic rows set north-to-south.

He also needed a screen of eucalyptus or poplars to protect the young buds from being blown off the trees in high winds, and cornstalks wrapped around the bases of the trees to protect them from animals.

There had to be a local water cooperative with a system of ditches and canals, run by a foreman — known as a zanjero — who kept a strict accounting of when the sluice gates were opened and for how long. He also needed to be patient, because trees didn’t grow on trees. They had to be nurtured in seedbeds, carefully planted in rows, and then left to mature for at least six years. But once a tree matured, it produced at least 800 pounds of oranges — 10 boxes worth — which had to be carefully clipped from the branches without nicks that could admit bacteria.

He needed a full complement of the bulbous metal devices known as “smudge pots,” which were set on the edges of the groves and set to burn used oil and rubber tires on winter nights so as to create a layer of thick smog over the trees, blanketing them from the bud-killing frost that tended to creep inward. Some of the more well-appointed ranches had electric thermometers in the fields that would set off an alarm inside the house in the middle of the night if the temperature dropped below freezing.

Most importantly of all, he needed a cheap labor base from April to November to pick and sort the fruit if the orchard was big enough. The first field-workers were Chinese or Japanese, many of them former tracklayers who traded in their hammers for a canvas shoulder bag and a tall ladder. They also dammed rivers and dug canals that proved indispensible in the later prosperity of the region. The Chinese, in the words of one approving employer, were “industrious, peaceful, never drank and kept cleaner in body than the Indian did.”

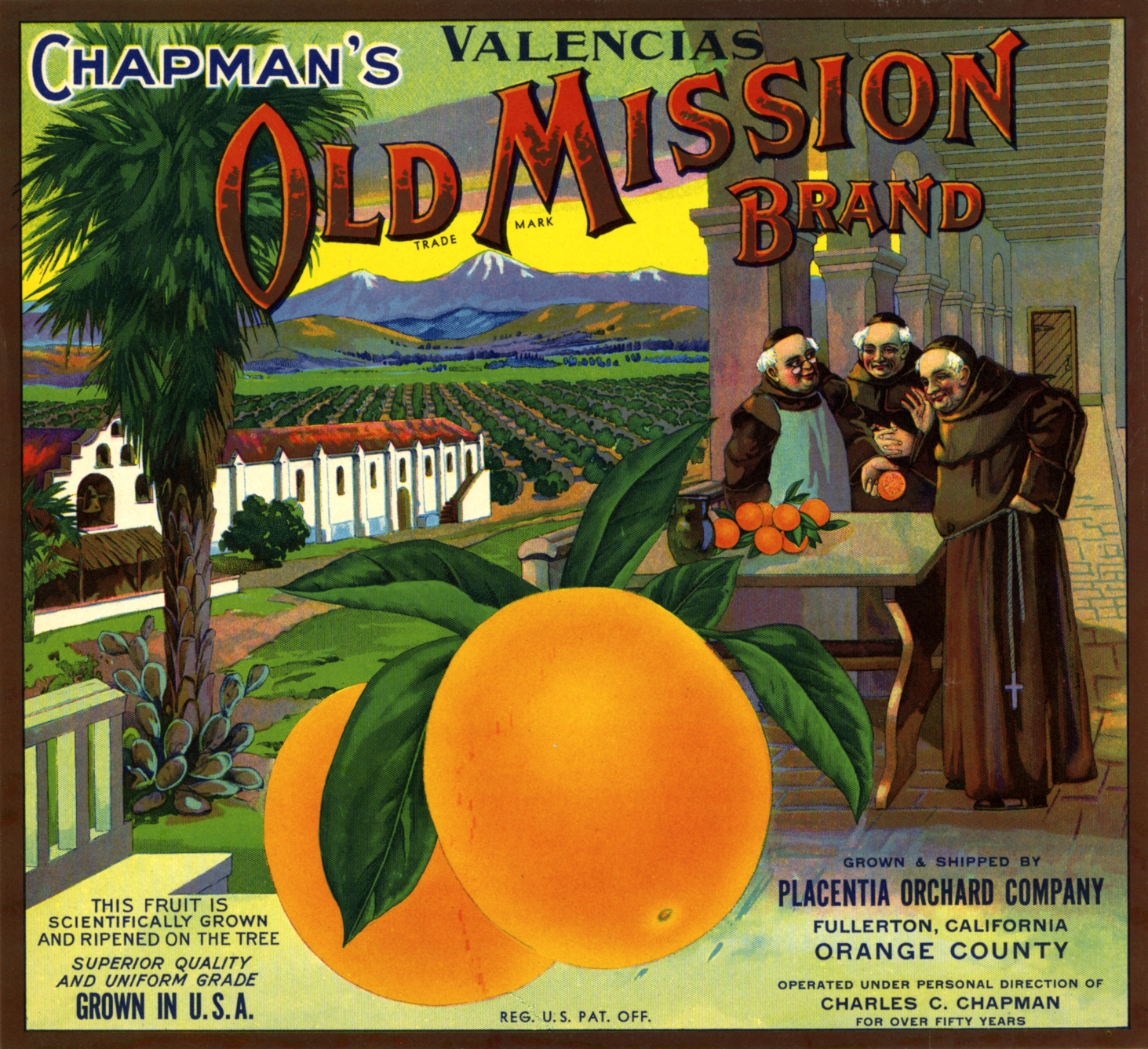

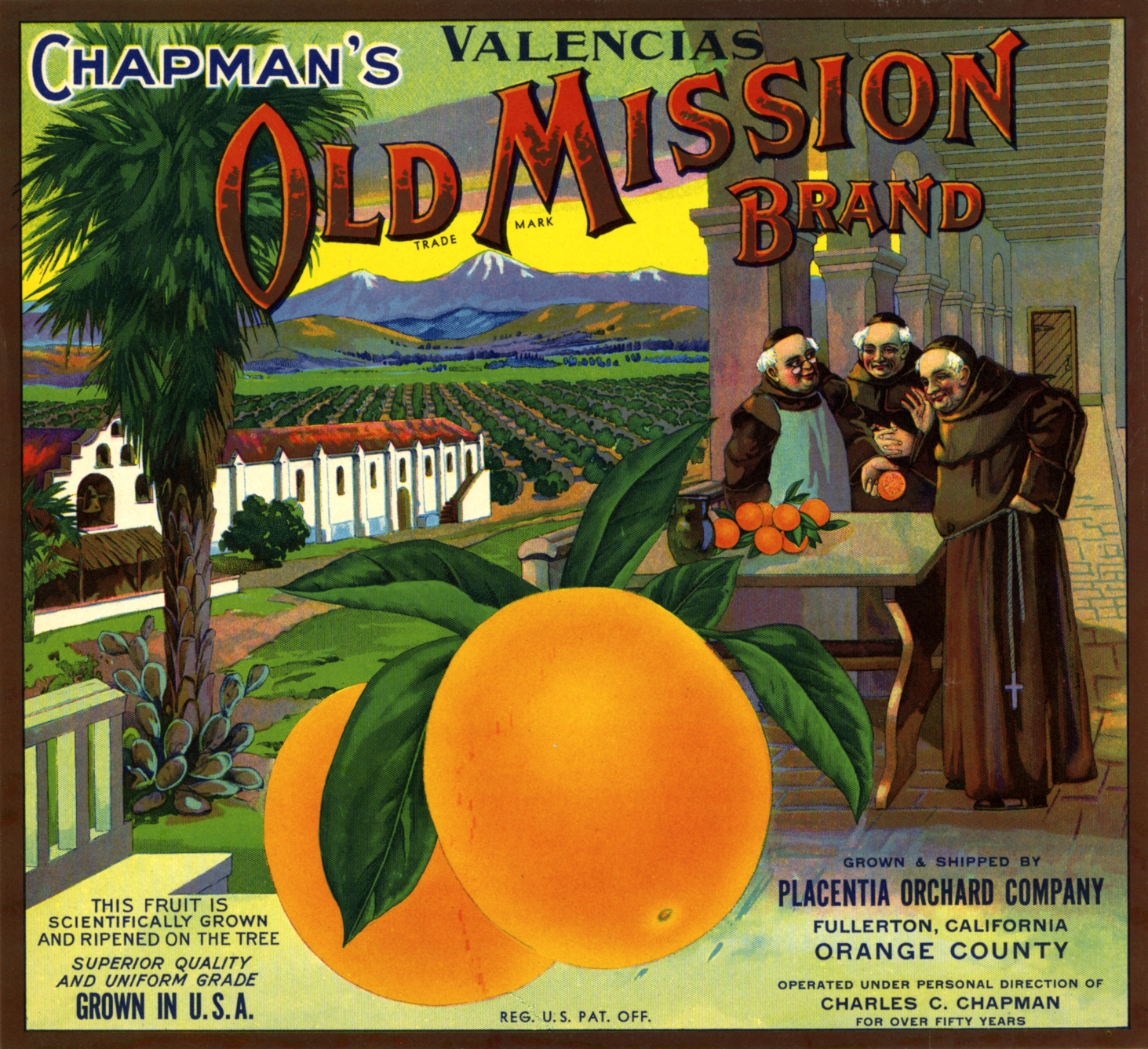

Mexican nationals gradually took the place of the Asians. Their wives typically worked in the packinghouses that sat astride the railroad tracks — measuring oranges with metal hoops, washing them in soap and water, treating the greenish ones with ethylene gas to warm their color, wrapping the fleshy spheres in thin paper stamped with a brand label, and arranging them into wooden crates plastered with colorful labels idealizing and eroticizing their own image and labor: buxom young women cradling sacks full of equally voluptuous oranges, against a backdrop of snowy mountain peaks and the spires of semi-ruined Catholic churches. The caricatures were so resplendent that many of these labels were framed and hung as artwork in distant living rooms.

The real life of the Latino fruit-picker or packer, of course, was not so picturesque. Wages were about two cents per box picked, and workers lived in rows of squalid shacks next to the canals. Orange resident Ken Schlueter, whose father owned 625 trees in the city when he was growing up in the 1950s, recalled being sent out to work alongside the Mexican crews, his well-to-do father’s way of imparting a work ethic. They would bring him homemade tacos that they had heated up with hot coals buried inside the earth. He always felt outdone on the ladders, for his co-workers were rapid and precise, fleecing each tree from the top on down, making the oranges rain down to the earth in a cannonade of soft thuds. “Their hands were in constant motion,” he told me. Harvesting oranges was a far more labor-intensive enterprise than stripping an Iowa farm of corn and wheat. “One acre here took as much work as a hundred acres in the Midwest,” said Schlueter.

In brand-new settlements like Pasadena, Pomona, Riverside, Orange, and Santa Ana, the transplanted citrus elite like the Schlueters and their families found a “new El Dorado” and built Victorian houses, libraries, churches, and small opera houses — recreating the cities of a more established America, according to familiar patterns. A group of German immigrants from Ohio founded St. John’s Lutheran Church in the city of Orange and built a pink and gray Gothic Revival sanctuary in 1913 that would have looked entirely at home in a cozy suburb of Cincinnati. The citrus trade was, said William Andrew Spalding, “an industry suited to the most intelligent and refined people.”

But instead of seas of wheat or corn around them, there were phalanxes of the fragrant trees — once viewed as a romantic gift of the Spanish padres, produced now for the more Yankee virtues of thrift, industry, and bulk commodities. Orange County became, in the words of historian Phil Brigandi, “one vast orchard, dotted with little towns.” Folded between the chain of tourist villages on the Pacific Coast and the range of the Santa Ana Mountains to the east, the county was a matrix of groves, dirt roads, windmills, and canals: “wall-to-wall trees,” in the recollections of Ken Schlueter.

The Santa Fe and Southern Pacific Railroads, hubbed in Los Angeles around a mini-city of cold storage warehouses, linked this archipelago society of sweet fruit to the rest of the country. The polycentric foundations of modern Southern California were laid down through this interconnection between the orchards and their bulk storage, a network that would later provide the essential skeleton of the modern freeway system.

Typical among the Tom Sawyers who arrived for Orange County’s second act was Charles C. Chapman, who had been an ambitious young seller of apples next to the railroads tracks in his Illinois hometown. He later operated a telegraph and had gotten rich off writing and publishing local histories across the Midwest. At the age of 41, he moved to warm Los Angeles for his wife’s health and bought a “sadly neglected” grove near Placentia, almost as a hobby. When he wanted to visit it, he rode the Santa Fe Railroad to Fullerton — a town where he would later become the Republican mayor — and peddled his bicycle eight miles out to the oranges.

What made him atypical was his willingness to take creative risks in crop cultivation and sales. Chapman figured out that, unlike the Washington navel oranges which dominated the business, Valencia oranges could be left on the trees an extra six months after ripening and then shipped east in August — a season in which buyers were not accustomed to seeing oranges.

He also cut down on spoilage by insisting that his pickers wear leather gloves and cut the stems with rounded-tip clippers in such a way as not to leave small gashes that eventually harbored mold and could spoil an entire crate. After he shipped an initial carload of fruit back East at the end of the summer of 1897 — a rail voyage that recreated Joseph Wolfskill’s famous shipment to St. Louis — he made a huge profit and Valencia orange trees soon took over the inner folds of the coastal plains.

Chapman created a brand with an especially sumptuous crate label, featuring a ridiculous fantasy landscape of snowy peaks, palm trees, cactus, and, in the foreground, a group of portly Catholic monks inspecting a freshly picked orange with amazement and delight. Scientifically grown, proclaimed the advertising. The iconography and the brand name, Old Mission, were plucked directly from the hype surrounding the novel Ramona by Helen Hunt Jackson, which told the story of a mixed-race Indian girl growing up on a ranchero. The romantic portrayal sparked a touristic craze for Southern California and its vanilla-Mexican curios.

Chapman’s fame grew in this atmosphere. The trade press ran fawning stories on him, and one editor offered him $50,000 cash for the privilege of selling oranges for two years under the Old Mission brand. (Chapman declined the offer.) “He is indeed the ORANGE KING, not only of America but also of the world,” proclaimed the Fruit Trade Journal in 1905. Chapman molded himself into a Southern California version of Ben Franklin, making himself both eminently useful to those around him and phenomenally rich.

Chapman joined the boards of hospitals, banks, and Christian missionary societies, married a pretty young second wife from the church choir, got himself elected mayor of Fullerton, founded a newspaper, and built a rambling 13-room mansion. He even persuaded the Santa Fe Railroad to build a branch line out to his orchard. Despite never having gone to college himself, he put forward nearly half a million dollars in a nationwide fundraising challenge to revive the fortunes of a moribund Bible school and rebrand it as Chapman College (a name he swore was chosen by the trustees without his knowledge). His interest in Christian education was topped only by a young orange farmer named Charles Fuller, who used the oil-drilling royalties from his orchard in Placentia to put himself through Bible school. Fuller went on to a career as an international radio evangelist as the host of The Old-Fashioned Revival Hour and founded the influential Fuller Theological Seminary.

Chapman’s own evangelism on progress and American values was a regular crowd-pleaser at the California Valencia Orange Show, a kitschy 1920s fair called a “fairyland of fruit” by the Santa Ana Daily Register. The child-friendly show embodied much of the exuberance and goofiness of the Jazz Age: fake Arabic minarets, models wearing bathing suits, high towers of fruit, parades and floats, congratulatory phone calls from the president of the United States.

This fair was the public face of the California Fruit Growers Exchange, a powerful oligarchy that functioned as a seller’s ring. Independent farming had never worked out very well in Orange County. In the early days, a grower had no choice but to sell his crop to any number of agents representing the packinghouses who would estimate a price based on what they saw on the trees — and this price was often a result of collusion. Some Orange County growers were persuaded to sell their fruit on consignment, which meant that if it showed up in Chicago as spoiled pulpy mush, they got nothing in return. Brokers could also falsify their spoilage reports and deal contraband oranges on the black market.

Fed up with the disorganized system, a number of powerful growers formed the California Fruit Growers Exchange in 1905 to share packinghouses, codify grading standards, and stabilize prices. It functioned like a nonprofit, owning no property and selling no shares, but it commanded enormous power, employed a national network of salesmen, and paid huge telegraph bills. They pooled the annual crops of Washington navels and Valencias from various districts around Southern California and sold them in bulk. Train schedules and deliveries were coordinated out of a high-gated office on Glassell Street in downtown Orange that looked more like a Middle Eastern temple than a place of business.

Despite the pro–small business rhetoric of most growers, this was not lassiez-faire economics at work, nor did it really resemble a Jeffersonian democracy of small landholders. This was, in the words of historian Laura Gray Turner, the essence of “managerial corporate capitalism.” Led by a dapper ex–US Department of Agriculture man named G. Harold Powell, the exchange functioned as a legal monopoly that happened to be exempt from antitrust laws; fewer than 200 men owned plots of more than 100 acres. The Orange County elite made the decisions and controlled the prices.

Charles Chapman was one of the notable holdouts: he feared the brand power of Old Mission would be diluted if he had to sell through a single channel. But like the CFGE, he was not above bending the rules of free enterprise and engaging in outright market manipulation. “It was early evident that California citrus could not, without protection, successfully compete with foreign fruit, especially from Italy and Spain,” he wrote in his autobiography.

In 1908, Chapman and several associates lobbied the House Ways and Means committee for a one-cent-per-pound tariff on European oranges, which opened up the ports of Boston and New York to his higher-priced goods. And when he got news of a shipment coming across the Atlantic in spite of the stiff duties, he played hardball. “When a consignment of foreign fruit came into the harbor and was offered for sale, a sufficient amount of our fruit was offered on the market to depress it or break it” — usually about 100 train cars “donated to be sacrificed on these markets.” Like a generation of 19th-century monopolists before him, Chapman and his allies also pressured the railroads for special-rate deals. When the tariff again came up for reconsideration in 1913, Chapman made a special plea for the “fostering care that our Government has always been good enough to give new industries.” California thus muscled its way into Eastern iceboxes.

The rise of the CFGE and the era of Big Fruit came with a wave of orchard consolidation and the end of the “gentleman farmer” way of life in Orange County. Yet it ordered the market in times of uncertainty, created new year-round markets, and made large investments a little safer. Oranges were still a notional product, ranking nearly as frivolous and childlike as candy. There were up to five million orange trees in Southern California by that time, serving a national appetite that could turn fickle at any moment.

In the early decades of the 20th century, Orange County faced an imbalance dreaded by every manufacturer: an overabundance of product not matched by rising demand. The ad agency of Lord & Thomas — and its in-house poets — dreamed up a campaign to boost sales that played off popular fear. The disaster of the Spanish Flu epidemic during World War I had made Americans more germ-conscious than ever. But the pasteurization process had recently made it possible to rid a beverage of bacteria.

Lord & Thomas came up with the simple slogan “Drink an Orange” to promote the simple but excitingly novel idea of having a glass of juice at breakfast — adding a morning eating ritual, in liquid form, which had been practically unknown before. Breakfast was “a habit meal,” said the agency, not prone to much variance from day to day. And in that morning ritual was the possibility — if not the expectation — of daily consumption of a fruit thus far regarded as a dessert delicacy. “Its delicious juice is as invigorating as it is palatable,” said Charles Chapman in one of his many speeches, “giving to man increased nerve power and a clear brain.”

Orange County’s liquid product took on the name of an earlier CFGE brand called “Sunkist,” which evoked in a single phrase what had been portrayed in all the kitschy art on all the wooden crates over the years. The name graced billboards across the nation, educational films passed out to public schools, huge neon displays in Times Square and Coney Island. “Thanks to admen,” wrote historian Jared Farmer, “the sweet orange completed its trajectory from fruit of the gods to the aristocracy to the bourgeoisie to the average Joe.” Vitamin C would not be isolated in a laboratory and clearly understood until 1932, but the mysteriously healthful qualities of orange juice were all over the press.

The word Sunkist became so popular that the CFGE adopted it as the new name for the organization and stamped it directly on the oranges in black ink. Oranges, and orange juice, had found their direct competition not in other fruits but in sugared beverages like 7 Up and Coca-Cola, and Sunkist found its marketing strategy in the bright colors and salutary qualities of its product. Though it was not fizzy, it emerged from nature and not from the bottling plant. The advertising for Sunkist got so thick, wrote historian Douglas Cazaux Sackman, that nearly 1,500 Manhattan retail stores and soda fountains had bright orange advertisements plastered in their windows. At Christmas, a cartoon Santa Claus offered an orange as the “most healthful gift.”

Some of the local connotations of “Sunkist” were not nearly as radiant. In 1936, more than 2,000 naranjeros decided they had had enough of poor working conditions and put down their round-tipped clippers in an attempt to strike. But their uprising was doomed from the start. The local press, including The Santa Ana Register, portrayed them as disloyal saboteurs similar to the IWW Wobblies who had tried to organize factories around the time of the outbreak of World War I. According to historian and journalist Gustavo Arellano, one of the pickers bit a policeman’s arm, Mexican strikers were thrown in jail, and the Orange County sheriff gave “shoot to kill” orders, deputizing American Legion members to guard the orchards with shotguns. Hecklers broke up union meetings and police threw tear gas canisters through the windows.

The lawyer and journalist Carey McWilliams was appalled at the head-cracking he witnessed and coined the term “Gunkist” to describe the danger and violence roiling in the sun-splashed orchards. “Under the direction of Sheriff Logan Jackson, who should long be remembered for his brutality in this strike, over 400 special guards, armed to the hilt, are conducting a terroristic campaign of unparalleled ugliness,” McWilliams wrote in Pacific Weekly. In the end, growers agreed only to minimal wage hikes and no union.

As labor tensions reached fever pitch, the California orange empire was already wilting from a series of cultural and economic blows. The colorful crate labels had begun to shed their fanciful Raphaelite iconography in favor of the simple word “Sunkist” across a blue background; with the advent of chain groceries and cardboard boxes in the 1950s, the crates themselves became a memory. Tired of the industry’s smog — even uglier and more pervasive than the growing encroachment of car exhaust — municipalities all over the Southland began outlawing the smudge pots lit aflame on the edges of orchards on cold nights. A disease with the poetically clinical name of “quick decline” ran through the orchards, turning trees into dead sticks within a week. The blight spread through the ground, traveling root to root, and one sick tree could ruin all of its neighbors. Ken Schlueter recalled digging deep trenches around healthy trees, trying to keep them from dying.

And the most unstoppable force of all, even worse than quick decline: newly prosperous young couples sought detached ranch homes — a slice of the California good life — for themselves in the peace and prosperity in the early 1950s. Ten acres of orange trees started looking like a sucker bet compared to 40 new houses on quarter-acre lots. Schlueter’s father gave in and sold out after the city incorporated his property and raised his taxes.

In 1953, the movie studio chief Walt Disney acquired 160 acres of orange and walnut trees on Harbor Boulevard, right off the new Santa Ana freeway, with more profitable ideas than agriculture. The Stanford Research Institute had studied land growth patterns and real estate models and told him the spot was an ideal place for a new amusement park, whose design was based on a railroad fair that Disney had seen in Chicago five years prior. The bulldozers went to work on the morning of July 16, 1954, and the rise of Disneyland on a vanished bed of citrus was the highest-profile land conversion yet of what had already become an unstoppable change.

Within a decade, the citrus business hastened its move to the Central Valley, near towns like Visalia and Tulare, where land could be bought for a fifth of the cost. Orange County became a residential instead of agricultural satellite of greater Los Angeles — celebrating its namesake crop with bas-relief concrete displays on the noise-dimming walls of the Garden Grove Freeway, and a few remaining acres of symbolic trees that historical preservationists had to fight to keep. The “fruit frost service” reports disappeared from KFI radio.

Only locals who know what to look for today can see the faintly visible archaeology of the orange empire — from the Anaheim Orange & Lemon Association Packing House turned into a food court, to the Santiago Orange Growers Association building on a quiet street near the railroad tracks, waiting for Chapman University to find a re-adaptive use for it.

Orange County’s dominant industry lasted 70 years — which the Bible holds to be about the natural lifespan of a human being, the metaphorical flesh. It ultimately succumbed to the changing technologies of agriculture and the shifting economies of real estate that spelled a natural fate for the plantations. The same forces, in other words, that helped create them.

While the trunks of the last orange trees were burned and mulched decades ago, they left imprints that go deeper than the name of the county or the bulbous image on its seal. The echoing imprint of the citrus business can be perceived in the rectangular tract subdivisions that match the acreage of the orchards they replaced; within the segregated neighborhoods of Anaheim and Santa Ana, where the Latino grandchildren of the naranjeros live on the disadvantaged side of a racial rift as pronounced as anywhere in the Deep South; within the volubly conservative editorial page of the Orange County Register; within the cultural emphasis on overt displays of wealth and youthful voluptuousness as fetishized and misleading as any rural maiden pictured on a crate label.

Critics of Orange County look at the orchard-sized subdivisions, or the vast consumerist rectangle of South Coast Plaza, the smoked-glass office parks with grassy berms and bottlebrush trees out front, the chintzy Spanish Mission architectural vocabulary, the feeder avenues as wide as rivers, and declare the whole scene bland, monotonous, and corporate. But so were the orange plantations they replaced, if not more so.

A common tourist habit is to imagine what the scene might have looked like in a previous era, especially in older parts of the world. How did the coast of Virginia look to those English sailors, for example, or the cliffs of Capri to a Roman solider? This exercise is especially difficult in Orange County’s flat parts when you try to see through the wide-boulevard monoculture of Del Taco and Ralphs into a time not yet a century ago, when the roads were all dirt and the sun was blocked out by a mathematically precise forest of orange and lemon trees.

The trees are all gone now — sic transit gloria citrus — but they molded the county into what it is today, in the aspects we celebrate, and also those held up as regional jokes or stereotypes. There’s a reflexive tendency to think of our orange-ranching era in a golden light, perhaps because of the lost ethic of physical work or the pleasing taste of the fruit, but the reality was often contradictory and difficult. So it’s important not just to envision the vanished trees but to see them for what they really were.

Near the center of the college that Charles Chapman helped endow, and where I now teach, is a statue of our founder seated in an easy chair. He leans slightly forward as if telling a story or giving a piece of advice. A dwarf orange tree grows behind him. Carved on the back of this memorial are words from his autobiography, which describe the business strategy that vaulted him to prominence:

Words on stone monuments are not usually so practical and specific. But this inscription perfectly symbolizes what the promise of Orange County represented for an earlier generation. Civilizations both great and small are founded more on economic schemes than high moral purpose, which comes as an afterthought.

For 70 years, Orange County once stood for the harnessing of nature, the manipulation of distant capital markets, the production of sensual pleasure, the unapologetic mythologizing of an abundance not shared by all (especially those who picked the fruit), enjoyment of material success, the dependence on the Lord’s constant blessings of warm sun, cheap land, and frost-free air. It was a place that its citrus lords perceived to be free of history, leaving them free to make their own. This is the orange-ghosted world we live in today.

This essay will appear in the forthcoming anthology The Barricades of Heaven: A Literary Field Guide to Orange County, California, to be published by Heyday in 2017.

Tom Zoellner is the author of five nonfiction books, including Train: Riding the Rails that Created the Modern World. An Associate Professor of English at Chapman University, he lives in downtown Los Angeles.

¤

ALL FLESH is as the grass. This dour wisdom from the Book of Isaiah is also true in reverse: all plants are as flesh. Crops of the fields, like the humans who tend them, have their day and die.

For 70 years, the defining “grass” of Orange County was its namesake product: the sweet fruit that hung from relentless furrows of trees serrating the county from top to bottom. A group of well-off Protestant migrants from the Midwest tried to bring small-farm values to new 19th-century business with the size — and a dose of the heartlessness — of a Southern rice plantation. They managed to create an economy unlike any other in America, as well as a vast tablecloth of waxy leaves, windmills, and dirt farm lanes, all cloaked on chilly mornings in a man-made, frost-defying haze of oily smoke.

The citrus trees left long shadows. Orange County’s modern-day fetish for large tracts of single-family homes, the exploitation of Latinos as laborers, the decentered urban carpet, the bland mass culture, the self-conscious expression “California dream,” the thirst for youth and cosmetics, the Iowa-like probity: all of these local distinctions can be traced to the time between 1870 and 1950 when the orange was monocultured king, and the local economy arranged around it.

A first irony: oranges aren’t native to California. The sweet variety called mandarin emerged in China and Vietnam around the time of Confucius in 500 BCE, then crossed with a related fruit called pomelo. Jews used a hard and sour breed called citron for rituals in the Feast of Tabernacles; the Moors of North Africa are thought to have brought it in the eighth century to Spain, where it softened and sweetened through hybrid speciation to something resembling the Valencias and Washington navels we eat today. During the 15th century, scurvy-wary Spanish sailors brought these seedlings to what is now California, and small groves of sweet oranges were planted on the grounds of the missions that Junípero Serra created in his path up the coast.

But the local birthplace of Orange County’s signature business is less picturesque and not even in the county: it’s a lonely stretch of Alameda Street south of Fourth Street, at the scruffy edge of downtown Los Angeles, where the only landmarks today are a row of cold-storage seafood warehouses, a weeded-over set of railroad tracks, and a liquor distribution warehouse. No plaque marks the spot where an Anglo trader planted the first set of orange trees for a commercial purpose in Southern California.

That man was William Wolfskill, a Kentucky native who had drifted to Mexico as a mountain man and gotten involved in the frontier liquor business. He and a partner sold jugs of grain alcohol mixed with red pepper and a dash of gunpowder under the name “Taos Lightning” — a booze so vile it could “peel the hide off a Gila Monster,” in the words of historian Marshall Trimble. Wolfskill married his way into Mexican citizenship, and while passing through the dusty village of Los Angeles on the way to blaze a trail to the Pacific from Santa Fe, figured that Southern California’s climate would support a citrus trade.

He acquired seeds from Serra’s 35 trees that grew near the Mission San Gabriel Arcángel and planted them near his farmhouse. There he grew rich exporting his juicy food up the coast by horse cart to the gold-rush camps near Sacramento. By the time of his death in 1866, he owned two-thirds of the orange trees in the state.

Wolfskill’s son and business heir Joseph thought even bigger. He understood that local markets were never the future of the California orange; the real money lay in shipping them to places where the fruit was an exotic species, a subject of rumor and fascination. Such was the intention of the first railroad shipment of oranges to St. Louis in 1877, in a single boxcar stacked high with crates stamped “Wolfskill California oranges.” In the lore of the California citrus trade, this was like the voyage of the Discovery, because new technology was about to make orange growers fantastically rich.

The ice-bunker car, which kept oranges cool with air blown over ice, debuted on the nation’s railroad tracks in 1889 — the same year the California Legislature approved the formation of Orange County as a separate political entity, and both the Southern Pacific and the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe feverishly extended their tendrils down to the brand-new farming boomtowns of Anaheim, Orange, and Santa Ana where the land was flat and gloriously empty. Huge fortunes could suddenly be made railing oranges east for customers eager to taste this high-priced exotic dessert.

The Southern Pacific Railroad also doubled-down on hype, popularizing the slogan “Oranges for Health, California for Wealth” and sending promotional trains to state fairs across the Midwest featuring traveling lecturers, glowing booklets, and free samples for locals to enjoy. Unlike heartland cash commodities such as wheat, corn, or oats — nutrient-dense but visually humble grasses — the California orange had an erotic maternal shape, and origins in the sun-splashed Mediterranean instead of gloomy steppes. Citrus sales doubled across the Midwest over the next decade, and some of the new consumers were persuaded to try out the California ranching dream for themselves.

These enterprising landowners tended to be Protestant, wealthy, middle-Western and middle-aged, and looking for a reinvention in the warm sun of a far land. This was, in the words of local antiquarian Charles Fletcher Lummis, “the least heroic migration in history, but the most judicious […]. [I]nstead of gophering for gold, they planted gold.”

The first job of a gentleman orange farmer was finding porous alluvial soil and nearby mountain ranges to provide shelter from restless Santa Ana winds. The best places were known to be immediately southwest of hill slopes, parallel to the wind and resistant to the “frost pockets” of stagnant cold air that could freeze the fruit off a tree in a single night. To best catch the sun’s rays, orange seedlings were planted 26 feet apart, in militaristic rows set north-to-south.

He also needed a screen of eucalyptus or poplars to protect the young buds from being blown off the trees in high winds, and cornstalks wrapped around the bases of the trees to protect them from animals.

There had to be a local water cooperative with a system of ditches and canals, run by a foreman — known as a zanjero — who kept a strict accounting of when the sluice gates were opened and for how long. He also needed to be patient, because trees didn’t grow on trees. They had to be nurtured in seedbeds, carefully planted in rows, and then left to mature for at least six years. But once a tree matured, it produced at least 800 pounds of oranges — 10 boxes worth — which had to be carefully clipped from the branches without nicks that could admit bacteria.

He needed a full complement of the bulbous metal devices known as “smudge pots,” which were set on the edges of the groves and set to burn used oil and rubber tires on winter nights so as to create a layer of thick smog over the trees, blanketing them from the bud-killing frost that tended to creep inward. Some of the more well-appointed ranches had electric thermometers in the fields that would set off an alarm inside the house in the middle of the night if the temperature dropped below freezing.

Most importantly of all, he needed a cheap labor base from April to November to pick and sort the fruit if the orchard was big enough. The first field-workers were Chinese or Japanese, many of them former tracklayers who traded in their hammers for a canvas shoulder bag and a tall ladder. They also dammed rivers and dug canals that proved indispensible in the later prosperity of the region. The Chinese, in the words of one approving employer, were “industrious, peaceful, never drank and kept cleaner in body than the Indian did.”

Mexican nationals gradually took the place of the Asians. Their wives typically worked in the packinghouses that sat astride the railroad tracks — measuring oranges with metal hoops, washing them in soap and water, treating the greenish ones with ethylene gas to warm their color, wrapping the fleshy spheres in thin paper stamped with a brand label, and arranging them into wooden crates plastered with colorful labels idealizing and eroticizing their own image and labor: buxom young women cradling sacks full of equally voluptuous oranges, against a backdrop of snowy mountain peaks and the spires of semi-ruined Catholic churches. The caricatures were so resplendent that many of these labels were framed and hung as artwork in distant living rooms.

The real life of the Latino fruit-picker or packer, of course, was not so picturesque. Wages were about two cents per box picked, and workers lived in rows of squalid shacks next to the canals. Orange resident Ken Schlueter, whose father owned 625 trees in the city when he was growing up in the 1950s, recalled being sent out to work alongside the Mexican crews, his well-to-do father’s way of imparting a work ethic. They would bring him homemade tacos that they had heated up with hot coals buried inside the earth. He always felt outdone on the ladders, for his co-workers were rapid and precise, fleecing each tree from the top on down, making the oranges rain down to the earth in a cannonade of soft thuds. “Their hands were in constant motion,” he told me. Harvesting oranges was a far more labor-intensive enterprise than stripping an Iowa farm of corn and wheat. “One acre here took as much work as a hundred acres in the Midwest,” said Schlueter.

In brand-new settlements like Pasadena, Pomona, Riverside, Orange, and Santa Ana, the transplanted citrus elite like the Schlueters and their families found a “new El Dorado” and built Victorian houses, libraries, churches, and small opera houses — recreating the cities of a more established America, according to familiar patterns. A group of German immigrants from Ohio founded St. John’s Lutheran Church in the city of Orange and built a pink and gray Gothic Revival sanctuary in 1913 that would have looked entirely at home in a cozy suburb of Cincinnati. The citrus trade was, said William Andrew Spalding, “an industry suited to the most intelligent and refined people.”

But instead of seas of wheat or corn around them, there were phalanxes of the fragrant trees — once viewed as a romantic gift of the Spanish padres, produced now for the more Yankee virtues of thrift, industry, and bulk commodities. Orange County became, in the words of historian Phil Brigandi, “one vast orchard, dotted with little towns.” Folded between the chain of tourist villages on the Pacific Coast and the range of the Santa Ana Mountains to the east, the county was a matrix of groves, dirt roads, windmills, and canals: “wall-to-wall trees,” in the recollections of Ken Schlueter.

The Santa Fe and Southern Pacific Railroads, hubbed in Los Angeles around a mini-city of cold storage warehouses, linked this archipelago society of sweet fruit to the rest of the country. The polycentric foundations of modern Southern California were laid down through this interconnection between the orchards and their bulk storage, a network that would later provide the essential skeleton of the modern freeway system.

¤

Typical among the Tom Sawyers who arrived for Orange County’s second act was Charles C. Chapman, who had been an ambitious young seller of apples next to the railroads tracks in his Illinois hometown. He later operated a telegraph and had gotten rich off writing and publishing local histories across the Midwest. At the age of 41, he moved to warm Los Angeles for his wife’s health and bought a “sadly neglected” grove near Placentia, almost as a hobby. When he wanted to visit it, he rode the Santa Fe Railroad to Fullerton — a town where he would later become the Republican mayor — and peddled his bicycle eight miles out to the oranges.

What made him atypical was his willingness to take creative risks in crop cultivation and sales. Chapman figured out that, unlike the Washington navel oranges which dominated the business, Valencia oranges could be left on the trees an extra six months after ripening and then shipped east in August — a season in which buyers were not accustomed to seeing oranges.

He also cut down on spoilage by insisting that his pickers wear leather gloves and cut the stems with rounded-tip clippers in such a way as not to leave small gashes that eventually harbored mold and could spoil an entire crate. After he shipped an initial carload of fruit back East at the end of the summer of 1897 — a rail voyage that recreated Joseph Wolfskill’s famous shipment to St. Louis — he made a huge profit and Valencia orange trees soon took over the inner folds of the coastal plains.

Chapman created a brand with an especially sumptuous crate label, featuring a ridiculous fantasy landscape of snowy peaks, palm trees, cactus, and, in the foreground, a group of portly Catholic monks inspecting a freshly picked orange with amazement and delight. Scientifically grown, proclaimed the advertising. The iconography and the brand name, Old Mission, were plucked directly from the hype surrounding the novel Ramona by Helen Hunt Jackson, which told the story of a mixed-race Indian girl growing up on a ranchero. The romantic portrayal sparked a touristic craze for Southern California and its vanilla-Mexican curios.

Chapman’s fame grew in this atmosphere. The trade press ran fawning stories on him, and one editor offered him $50,000 cash for the privilege of selling oranges for two years under the Old Mission brand. (Chapman declined the offer.) “He is indeed the ORANGE KING, not only of America but also of the world,” proclaimed the Fruit Trade Journal in 1905. Chapman molded himself into a Southern California version of Ben Franklin, making himself both eminently useful to those around him and phenomenally rich.

Chapman joined the boards of hospitals, banks, and Christian missionary societies, married a pretty young second wife from the church choir, got himself elected mayor of Fullerton, founded a newspaper, and built a rambling 13-room mansion. He even persuaded the Santa Fe Railroad to build a branch line out to his orchard. Despite never having gone to college himself, he put forward nearly half a million dollars in a nationwide fundraising challenge to revive the fortunes of a moribund Bible school and rebrand it as Chapman College (a name he swore was chosen by the trustees without his knowledge). His interest in Christian education was topped only by a young orange farmer named Charles Fuller, who used the oil-drilling royalties from his orchard in Placentia to put himself through Bible school. Fuller went on to a career as an international radio evangelist as the host of The Old-Fashioned Revival Hour and founded the influential Fuller Theological Seminary.

Chapman’s own evangelism on progress and American values was a regular crowd-pleaser at the California Valencia Orange Show, a kitschy 1920s fair called a “fairyland of fruit” by the Santa Ana Daily Register. The child-friendly show embodied much of the exuberance and goofiness of the Jazz Age: fake Arabic minarets, models wearing bathing suits, high towers of fruit, parades and floats, congratulatory phone calls from the president of the United States.

This fair was the public face of the California Fruit Growers Exchange, a powerful oligarchy that functioned as a seller’s ring. Independent farming had never worked out very well in Orange County. In the early days, a grower had no choice but to sell his crop to any number of agents representing the packinghouses who would estimate a price based on what they saw on the trees — and this price was often a result of collusion. Some Orange County growers were persuaded to sell their fruit on consignment, which meant that if it showed up in Chicago as spoiled pulpy mush, they got nothing in return. Brokers could also falsify their spoilage reports and deal contraband oranges on the black market.

Fed up with the disorganized system, a number of powerful growers formed the California Fruit Growers Exchange in 1905 to share packinghouses, codify grading standards, and stabilize prices. It functioned like a nonprofit, owning no property and selling no shares, but it commanded enormous power, employed a national network of salesmen, and paid huge telegraph bills. They pooled the annual crops of Washington navels and Valencias from various districts around Southern California and sold them in bulk. Train schedules and deliveries were coordinated out of a high-gated office on Glassell Street in downtown Orange that looked more like a Middle Eastern temple than a place of business.

Despite the pro–small business rhetoric of most growers, this was not lassiez-faire economics at work, nor did it really resemble a Jeffersonian democracy of small landholders. This was, in the words of historian Laura Gray Turner, the essence of “managerial corporate capitalism.” Led by a dapper ex–US Department of Agriculture man named G. Harold Powell, the exchange functioned as a legal monopoly that happened to be exempt from antitrust laws; fewer than 200 men owned plots of more than 100 acres. The Orange County elite made the decisions and controlled the prices.

Charles Chapman was one of the notable holdouts: he feared the brand power of Old Mission would be diluted if he had to sell through a single channel. But like the CFGE, he was not above bending the rules of free enterprise and engaging in outright market manipulation. “It was early evident that California citrus could not, without protection, successfully compete with foreign fruit, especially from Italy and Spain,” he wrote in his autobiography.

In 1908, Chapman and several associates lobbied the House Ways and Means committee for a one-cent-per-pound tariff on European oranges, which opened up the ports of Boston and New York to his higher-priced goods. And when he got news of a shipment coming across the Atlantic in spite of the stiff duties, he played hardball. “When a consignment of foreign fruit came into the harbor and was offered for sale, a sufficient amount of our fruit was offered on the market to depress it or break it” — usually about 100 train cars “donated to be sacrificed on these markets.” Like a generation of 19th-century monopolists before him, Chapman and his allies also pressured the railroads for special-rate deals. When the tariff again came up for reconsideration in 1913, Chapman made a special plea for the “fostering care that our Government has always been good enough to give new industries.” California thus muscled its way into Eastern iceboxes.

The rise of the CFGE and the era of Big Fruit came with a wave of orchard consolidation and the end of the “gentleman farmer” way of life in Orange County. Yet it ordered the market in times of uncertainty, created new year-round markets, and made large investments a little safer. Oranges were still a notional product, ranking nearly as frivolous and childlike as candy. There were up to five million orange trees in Southern California by that time, serving a national appetite that could turn fickle at any moment.

¤

In the early decades of the 20th century, Orange County faced an imbalance dreaded by every manufacturer: an overabundance of product not matched by rising demand. The ad agency of Lord & Thomas — and its in-house poets — dreamed up a campaign to boost sales that played off popular fear. The disaster of the Spanish Flu epidemic during World War I had made Americans more germ-conscious than ever. But the pasteurization process had recently made it possible to rid a beverage of bacteria.

Lord & Thomas came up with the simple slogan “Drink an Orange” to promote the simple but excitingly novel idea of having a glass of juice at breakfast — adding a morning eating ritual, in liquid form, which had been practically unknown before. Breakfast was “a habit meal,” said the agency, not prone to much variance from day to day. And in that morning ritual was the possibility — if not the expectation — of daily consumption of a fruit thus far regarded as a dessert delicacy. “Its delicious juice is as invigorating as it is palatable,” said Charles Chapman in one of his many speeches, “giving to man increased nerve power and a clear brain.”

Orange County’s liquid product took on the name of an earlier CFGE brand called “Sunkist,” which evoked in a single phrase what had been portrayed in all the kitschy art on all the wooden crates over the years. The name graced billboards across the nation, educational films passed out to public schools, huge neon displays in Times Square and Coney Island. “Thanks to admen,” wrote historian Jared Farmer, “the sweet orange completed its trajectory from fruit of the gods to the aristocracy to the bourgeoisie to the average Joe.” Vitamin C would not be isolated in a laboratory and clearly understood until 1932, but the mysteriously healthful qualities of orange juice were all over the press.

The word Sunkist became so popular that the CFGE adopted it as the new name for the organization and stamped it directly on the oranges in black ink. Oranges, and orange juice, had found their direct competition not in other fruits but in sugared beverages like 7 Up and Coca-Cola, and Sunkist found its marketing strategy in the bright colors and salutary qualities of its product. Though it was not fizzy, it emerged from nature and not from the bottling plant. The advertising for Sunkist got so thick, wrote historian Douglas Cazaux Sackman, that nearly 1,500 Manhattan retail stores and soda fountains had bright orange advertisements plastered in their windows. At Christmas, a cartoon Santa Claus offered an orange as the “most healthful gift.”

Some of the local connotations of “Sunkist” were not nearly as radiant. In 1936, more than 2,000 naranjeros decided they had had enough of poor working conditions and put down their round-tipped clippers in an attempt to strike. But their uprising was doomed from the start. The local press, including The Santa Ana Register, portrayed them as disloyal saboteurs similar to the IWW Wobblies who had tried to organize factories around the time of the outbreak of World War I. According to historian and journalist Gustavo Arellano, one of the pickers bit a policeman’s arm, Mexican strikers were thrown in jail, and the Orange County sheriff gave “shoot to kill” orders, deputizing American Legion members to guard the orchards with shotguns. Hecklers broke up union meetings and police threw tear gas canisters through the windows.

The lawyer and journalist Carey McWilliams was appalled at the head-cracking he witnessed and coined the term “Gunkist” to describe the danger and violence roiling in the sun-splashed orchards. “Under the direction of Sheriff Logan Jackson, who should long be remembered for his brutality in this strike, over 400 special guards, armed to the hilt, are conducting a terroristic campaign of unparalleled ugliness,” McWilliams wrote in Pacific Weekly. In the end, growers agreed only to minimal wage hikes and no union.

As labor tensions reached fever pitch, the California orange empire was already wilting from a series of cultural and economic blows. The colorful crate labels had begun to shed their fanciful Raphaelite iconography in favor of the simple word “Sunkist” across a blue background; with the advent of chain groceries and cardboard boxes in the 1950s, the crates themselves became a memory. Tired of the industry’s smog — even uglier and more pervasive than the growing encroachment of car exhaust — municipalities all over the Southland began outlawing the smudge pots lit aflame on the edges of orchards on cold nights. A disease with the poetically clinical name of “quick decline” ran through the orchards, turning trees into dead sticks within a week. The blight spread through the ground, traveling root to root, and one sick tree could ruin all of its neighbors. Ken Schlueter recalled digging deep trenches around healthy trees, trying to keep them from dying.

And the most unstoppable force of all, even worse than quick decline: newly prosperous young couples sought detached ranch homes — a slice of the California good life — for themselves in the peace and prosperity in the early 1950s. Ten acres of orange trees started looking like a sucker bet compared to 40 new houses on quarter-acre lots. Schlueter’s father gave in and sold out after the city incorporated his property and raised his taxes.

In 1953, the movie studio chief Walt Disney acquired 160 acres of orange and walnut trees on Harbor Boulevard, right off the new Santa Ana freeway, with more profitable ideas than agriculture. The Stanford Research Institute had studied land growth patterns and real estate models and told him the spot was an ideal place for a new amusement park, whose design was based on a railroad fair that Disney had seen in Chicago five years prior. The bulldozers went to work on the morning of July 16, 1954, and the rise of Disneyland on a vanished bed of citrus was the highest-profile land conversion yet of what had already become an unstoppable change.

Within a decade, the citrus business hastened its move to the Central Valley, near towns like Visalia and Tulare, where land could be bought for a fifth of the cost. Orange County became a residential instead of agricultural satellite of greater Los Angeles — celebrating its namesake crop with bas-relief concrete displays on the noise-dimming walls of the Garden Grove Freeway, and a few remaining acres of symbolic trees that historical preservationists had to fight to keep. The “fruit frost service” reports disappeared from KFI radio.

¤

Only locals who know what to look for today can see the faintly visible archaeology of the orange empire — from the Anaheim Orange & Lemon Association Packing House turned into a food court, to the Santiago Orange Growers Association building on a quiet street near the railroad tracks, waiting for Chapman University to find a re-adaptive use for it.

Orange County’s dominant industry lasted 70 years — which the Bible holds to be about the natural lifespan of a human being, the metaphorical flesh. It ultimately succumbed to the changing technologies of agriculture and the shifting economies of real estate that spelled a natural fate for the plantations. The same forces, in other words, that helped create them.

While the trunks of the last orange trees were burned and mulched decades ago, they left imprints that go deeper than the name of the county or the bulbous image on its seal. The echoing imprint of the citrus business can be perceived in the rectangular tract subdivisions that match the acreage of the orchards they replaced; within the segregated neighborhoods of Anaheim and Santa Ana, where the Latino grandchildren of the naranjeros live on the disadvantaged side of a racial rift as pronounced as anywhere in the Deep South; within the volubly conservative editorial page of the Orange County Register; within the cultural emphasis on overt displays of wealth and youthful voluptuousness as fetishized and misleading as any rural maiden pictured on a crate label.

Critics of Orange County look at the orchard-sized subdivisions, or the vast consumerist rectangle of South Coast Plaza, the smoked-glass office parks with grassy berms and bottlebrush trees out front, the chintzy Spanish Mission architectural vocabulary, the feeder avenues as wide as rivers, and declare the whole scene bland, monotonous, and corporate. But so were the orange plantations they replaced, if not more so.

A common tourist habit is to imagine what the scene might have looked like in a previous era, especially in older parts of the world. How did the coast of Virginia look to those English sailors, for example, or the cliffs of Capri to a Roman solider? This exercise is especially difficult in Orange County’s flat parts when you try to see through the wide-boulevard monoculture of Del Taco and Ralphs into a time not yet a century ago, when the roads were all dirt and the sun was blocked out by a mathematically precise forest of orange and lemon trees.

The trees are all gone now — sic transit gloria citrus — but they molded the county into what it is today, in the aspects we celebrate, and also those held up as regional jokes or stereotypes. There’s a reflexive tendency to think of our orange-ranching era in a golden light, perhaps because of the lost ethic of physical work or the pleasing taste of the fruit, but the reality was often contradictory and difficult. So it’s important not just to envision the vanished trees but to see them for what they really were.

Near the center of the college that Charles Chapman helped endow, and where I now teach, is a statue of our founder seated in an easy chair. He leans slightly forward as if telling a story or giving a piece of advice. A dwarf orange tree grows behind him. Carved on the back of this memorial are words from his autobiography, which describe the business strategy that vaulted him to prominence:

I knew from experience that there were periods when citrus fruits were entirely absent from markets in the East, and I believed that if I could get oranges to customers during those periods I might develop a really profitable trade. So I took my courage in my hands and delayed any Valencia picking until long after all the other varieties had gone. Then we shipped [our oranges on] our first experimental [railroad] cars. The response was beyond my greatest expectations. The “trade” eagerly accepted this new variety, which was solid, juicy, long-keeping and delicious.

Words on stone monuments are not usually so practical and specific. But this inscription perfectly symbolizes what the promise of Orange County represented for an earlier generation. Civilizations both great and small are founded more on economic schemes than high moral purpose, which comes as an afterthought.

For 70 years, Orange County once stood for the harnessing of nature, the manipulation of distant capital markets, the production of sensual pleasure, the unapologetic mythologizing of an abundance not shared by all (especially those who picked the fruit), enjoyment of material success, the dependence on the Lord’s constant blessings of warm sun, cheap land, and frost-free air. It was a place that its citrus lords perceived to be free of history, leaving them free to make their own. This is the orange-ghosted world we live in today.

¤

This essay will appear in the forthcoming anthology The Barricades of Heaven: A Literary Field Guide to Orange County, California, to be published by Heyday in 2017.

¤

Tom Zoellner is the author of five nonfiction books, including Train: Riding the Rails that Created the Modern World. An Associate Professor of English at Chapman University, he lives in downtown Los Angeles.

LARB Contributor

Tom Zoellner is an editor-at-large at LARB and a professor of English at Chapman University. He is the author of eight nonfiction books, including The Heartless Stone, Uranium, The National Road, Rim to River, and Island on Fire, which won the 2020 National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction and was a finalist for the Bancroft Prize in history.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Golden Muse

A brief survey of gold mining literature across the Americas.

Where Criticism Is Counterrevolutionary: Tania Bruguera on Cuba and the Fight for Free Speech

An exclusive interview with Tania Bruguera following the Havana Biennial exhibition of art.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2016%2F04%2FHistoire2-1.png)