¤

IN 2021, HARVARD’S Houghton Library of rare books and manuscripts will reopen with an exhibition on women authors. At the moment, George Eliot, Phillis Wheatley, Amy Lowell, Mary Wroth, Charlotte Brontë, Zora Neale Hurston, Virginia Woolf — the list goes on — are sitting far apart from one another in the stacks, isolated on separate shelves and surrounded by many better-known male authors. In their own times, these women were lonely fighters for cultural authority in professional worlds that often questioned their identities, refused to print their work, and required them to revise and resubmit under male names. Their stories speak to the lived experiences of women professionals today.

Since the onset of COVID-19, women’s careers, especially in the humanities, have been increasingly undervalued. We’re being disproportionately dismissed from jobs, asked to work without pay, and expected to care for our children and families before ourselves. Some women authors, notably in Oxford University’s May 2020 Tolkien Symposium, have discussed whether or not writing is an appropriate way to give care, defending their stories as nourishment.

It’s as though we’ve wound back the clocks to Victorian England.

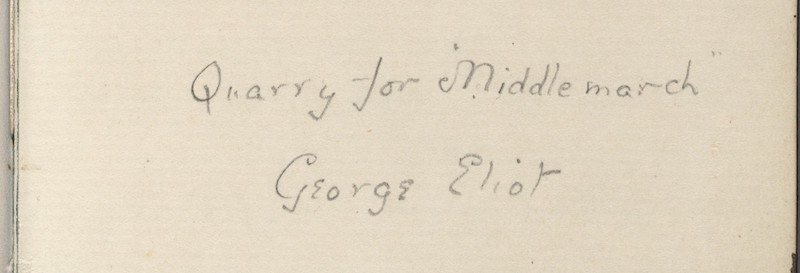

In 1871, Mary Ann Evans had been publishing for over a decade as “George Eliot.” A male pseudonym was her first line of defense against a risk that all women faced at the time: having their work ridiculed as, in Evans’s own words, “silly novels by lady novelists.” With male critics maligning women’s novels, not to mention their rights to education and careers outside the home, Evans signed even her own notebooks “Eliot,” and it is under that name that she is remembered today.

Yet the contents of Eliot’s private notebooks, which she called “Quarries,” would have been a slap in the face to the male naysayers. Her Quarry for Middlemarch is loaded with cutting-edge medical research and sharp political commentary regarding the cholera epidemic that wracked England in the 1830s. A simulacrum of Coventry, where Eliot attended Miss Franklin’s school for girls, the town of Middlemarch narrowly avoids its own outbreak in the novel — but it certainly doesn’t dodge the sociopolitical injustices and scientific debates surrounding medical reform in England.

If her Quarry is any indication, Eliot built Middlemarch around the figure of Dr. Tertius Lydgate. Over the course of the novel, Lydgate’s elite education — a medical degree from Edinburgh, extended study in London, and practice in Paris, all carefully mapped out in the Quarry — serve as the credentials for a uniquely capacious career. His soap-opera surgeon’s charm also helps. Lydgate’s romantic and medical projects provide a one-man through-line, spanning all the major social groups of Middlemarch. Even the scandal that ends with one man’s death and another’s disgrace, as well as Lydgate’s own departure from the town, only strengthens his friendship with Eliot’s fictional alter ego, Dorothea Brooke.

I am far from the first reader to notice how medical events connect the characters of Middlemarch with one another and with Eliot’s Quarry. In 1949, Professor Anna Kitchel traveled from Vassar College to the Houghton Library to transcribe and publish the Quarry. Her introduction dwells on Eliot’s medical research, and she identifies several doctors who may have inspired the figure of Lydgate. Although Kitchel is modest regarding her own grasp of Eliot’s research — “a professor of English is hardly equipped to produce a sound study on that subject” — she did publish a paper on the topic in Transactions and Studies of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in 1945. Eliot would have been proud.

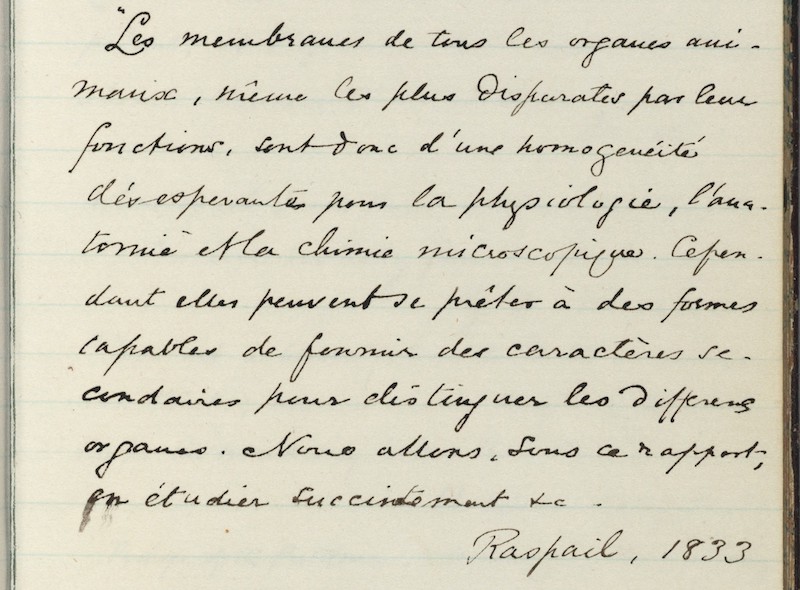

Unlike Kitchel, Eliot was confident from the first in her own ability to write about the medical innovations of her day. Whereas the second book that makes up the Quarry — in which the author sketches out the social and romantic action of Middlemarch — is full of cross outs, scribbles, and subtly rephrased repetitions, Book One, which features her medical research, is neatly composed, written with bold intention. With a steady hand and few emendations, Eliot inserts her own voice and opinions into debates lifted from Rapsail’s Noveau système de chimie organique fondé sur des nouvelles methodes d’observation (1833), Gerhard and Pennock’s research on typhoid fever in Philadelphia (1836), Sir Thomas Watson’s Lectures on the Principles and Practice of Physic (1843), and T. H. Huxley’s “The Cell-Theory” (1853), among many other works of both practical advice and pure science. Dr. Lydgate’s scientific interests and experiments mark him as a medical practitioner of rare intellect and nerve — that is, of Eliot’s own caliber.

Eliot’s personal interests in medicine extended beyond Lydgate’s fascination with pure science, into the politics of who was allowed to study and practice. She was particularly attuned to the privileges of the College of Physicians, namely their decree that “no physician, if he be not a graduate of Oxford or Cambridge, shall practise in London without one of their licenses.” Focusing on the College, the Quarry traces the history of medical accreditation in England, Scotland, and Paris since the 16th century. Eliot was captivated by conflicts between the College and lawmakers, and she copied down a satiric jab that Sir Robert Christison, president of the College during the 1840s, leveled at Parliament: “From the reign of Henry VIII to Geo. IV there is neither a charter nor an act of Parlt. on the subject of Medical Polity, which would not disgrace the lowest mechanics’ club.”

The sharp humor with which Eliot first approaches her research soon grows into critique. Within the first 10 pages of the Quarry, she displays a strong sense of social justice, addressing Britain’s history of unequal access to medical care and clinical degrees. She comments that, during the reigns of James I and Charles II, it was “[c]urious to observe, on the one hand, the College of Physicians procuring a law enabling them to prohibit surgeons from practising physic, & on the other, a law authorizing themselves to practise surgery.” Her tone shifts from wry to angry as she notes the “[i]nefficiency, nay arresting action, of the Colleges in all great medical inquiries” in her own time. The “privileges” of the Colleges, she suggests, were ill-placed in the hands of the London elite, and had been for centuries.

Why then would Eliot place the narrative reins of Middlemarch in the hands of Dr. Lydgate, fresh out of his College-sanctioned training in London and Paris? The answer lies in her activist attention to the rights of doctors to establish “country hospitals.” Throughout Middlemarch, Lydgate’s foremost ambition is to found a “Fever Hospital,” in which he might study — and train doctors to treat — highly contagious diseases that would otherwise end up contaminating a general hospital ward. Fever hospitals were still cutting-edge when Eliot was drafting her Quarry in the 1860s, and Lydgate may have been based on Dr. Sir Clifford Allbutt, who served at one of England’s earliest such centers, The Leeds House of Recovery, in 1861.

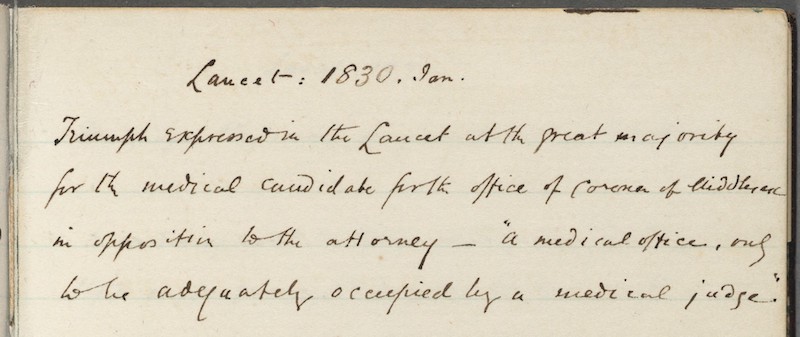

Eliot pulled most of her data on country hospitals from one (politically biased) source: The Lancet, which still publishes today (and still gets into controversies). The Quarry mentions the journal’s founder, Dr. Thomas Wakley, more than any doctor besides Lydgate, and if Lydgate’s aspirations are any indication, Eliot subscribed to Wakley’s position that “the county hospitals are better than the London: the men as eminent, the hospitals not so crowded with pupils.” Had Eliot not created the fictional Lydgate, she could have made Wakley’s own story into a novel.

Wakley founded The Lancet in 1823 after a gruesome case of mistaken identity shut down his fashionable practice in London. In 1820, the young, newly married Wakley was ambushed and beaten in his own home by men who thought him a murderer. They accused him of participating in a Republican gang that had perpetrated the back-alley beheading of their companions. By some accounts, these assailants burned Wakely's house to the ground when they had finished knocking him unconscious. The story of Wakely's attack was passed around London for the next few years, while he unsuccessfully fought for compensation from his insurance company. While his body healed, his bank account and reputation were wounded, forcing him to relocate and scale down his medical practice. Although most historical records report that Wakely was never in a Republican gang, he had cultivated leftist opinions while studying medicine. When he closed his fashionable practice, he found the time to confront his conservative medical community head-on. How ironic it must have been, for his anti-left assailants, to learn of Wakely's radical activism in The Lancet.

Eliot was captivated by Wakley’s democratizing project, especially his desire to disentangle medical reform from political power. The first page of her Quarry begins, “Triumph expressed in the Lancet at the great majority for the medical candidate for the office of Coroner of Middlesex in opposition to the attorney — ‘a medical office, only to be adequately occupied by a medical judge.’” Likewise, Middlemarch introduces Lydgate as a medical man intervening in the town council’s previously political efforts to organize a new hospital.

The stakes for his fever hospital are high. Although cholera never directly manifests in Middlemarch, it looms in the background, decimating other country towns with little predictability. Much as we’re tracking COVID-19 across the United States today, riveted by hospital reports, so, too, did England’s Annual Register from 1820–’32 — and Eliot’s Quarry — map England’s cholera outbreak. Eliot counted deaths across the country, noting that, “[a]bout the end of March, 1832, there have been 1530 cases in London, deaths 802. Quarantine to guard against it in England, June 13, 1831.” While the rest of England was under quarantine, the residents of Middlemarch were going about their lives as usual, relying on Dr. Lydgate to provide his newfangled fever hospital should the disease suddenly strike. No wonder Lydgate’s meetings with the town council are so fraught with eventually explosive tension.

Outside of Middlemarch, progressive and highly educated doctors were hard to come by. It wasn’t conceivable to conjure a fever hospital on demand. According to Eliot’s Quarry, London doctors and legislators remained unresponsive to the cholera outbreak until it showed up on their own doorsteps. Eliot was moved to write at length about the heroic work of the country doctors and untrained volunteers who fought the disease elsewhere, even in Lydgate’s Edinburgh:

In Edinburgh funds had been supplied by voluntary subscription, & labour & attendance by active charity, in clothing & feeding the poor, which […] set the invader at defiance, & when he arrived deprived him of almost all his terror. Hitherto the legislature had been silent. All at once, without apparently having lighted on any intermediate place, the disease appeared in London, & forthwith bills were hurried through parliament (both Houses) vesting in the privy council very ample powers to direct sanatory [sic] measures, & authorizing assessments to cover the necessary expenses.

The “active charity” that Eliot imagines as the protecting force against the invading, terrifying disease came in large part from the women of Edinburgh. Although these women would have been denied medical education and political power in London, they were encouraged throughout the 19th century to spearhead Britain’s charitable works.

Eliot’s fictional depiction of 1830s England wouldn’t qualify as realism if she had made her elite doctor a woman. Yet what made Lydgate’s character and career truly believable is the fact that it took the “active charity” of a woman to save it. Middlemarch’s other main protagonist, Dorothea Brooke, a thinly veiled version of Eliot herself, connects with Lydgate surprisingly late in the novel. Although Dorothea and Lydgate are aware of one another from early on, it seems that, until the novel’s climax, they have never interacted beyond one being a patient’s kin and the other his doctor. Dorothea approaches Lydgate when no one else in the town will — after he’s been saddled with a whopping 1,000 quid of debt (around £115,000 today), a hollow marriage, and suspicion that he might have sanctioned the murder of a patient. Dorothea offers Lydgate a generous financial gift to continue his work on the fever hospital. At the beginning of Middlemarch, all that Dorothea wants is to learn how best to serve her community, and by its conclusion, she is painfully aware of the disparities in men’s and women’s respective abilities to study and serve.

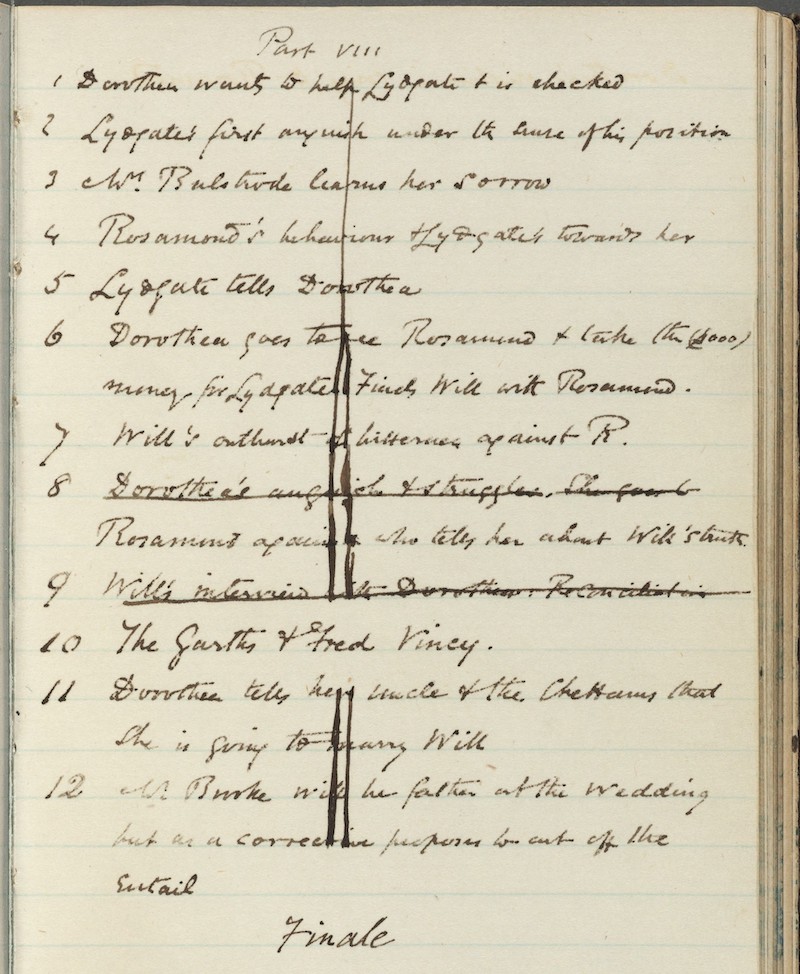

Eliot’s Quarry preserves her intention, from page one, to build up to this ideological encounter between woman activist and progressive country doctor. Book Two preserves her plot sketches, which repeat, expand, and fine-tune Dorothea and Lydgate’s final conversation. Eliot uses all her research in Book One to painstakingly map out the medical facts that lead to Lydgate’s scandal, with an attention to detail only matched in her outline for Dorothea’s subsequent aid. Her Quarry arrives at its “Finale,” untangling its many romantic subplots, only after cinching the details of “Lydgate’s outpouring to Dorothea,” sketching out how “Dorothea wants to help Lydgate & is checked,” and how she then “goes to see Rosamond [Lydgate’s wife] & takes (the £1000) money for Lydgate.” The future of Middlemarch’s fever hospital and the lives of the whole town, spared from epidemic by chance, hang in the balance of Dorothea’s intervention.

And then Dorothea marries. She has a baby. Lydgate leaves Middlemarch. He sets up a modest practice in another country town. The fever hospital goes unfinished. The vast bulk of Eliot’s medical research, so clearly excavated in her Quarry, runs just beneath the surface of the novel, holding it all together. Indeed, it is thanks to this “lady novelist” — writing fiction under a man’s name and taking on the politics of a man’s profession — that general readers today can begin to learn about the medical practices, debates, and social inequalities of Eliot’s time.

When the Quarry for Middlemarch emerges from Harvard’s underground stacks in 2021, a team of women curators will display it alongside the works of other women authors, in an exhibition that seeks to change how literary history is taught and who gets remembered. We will be putting a few famous books, including Eliot’s, next to many forgotten or seldom-read stories, in an effort to reimagine, represent, and rectify gendered and socioeconomic inequalities in a post-pandemic world.

¤

Joani Etskovitz is a PhD candidate in English Literature at Harvard University. A Beinecke and a Marshall Scholar, she holds two Masters degrees from the University of Oxford. Joani is currently co-curating and designing public programs for two 2021 exhibits at Harvard’s Houghton Rare Books Library: on “Women Authors, Authorizing Themselves” and children’s literature. You can find her on Twitter @JEtskovitz.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Provincial Reader

Sumana Roy reflects on the loss — or the proliferation — of the provincial reader.

Hampering Threadlike Pressure: A New Biography of George Eliot

Paul Delany reviews a new biography of George Eliot.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F08%2FEstkovitzEliot.png)