Looking for Léontine: My Obsession with a Forgotten Screen Queen

By Maggie HennefeldSeptember 24, 2019

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2019%2F09%2FHennefeldLeontine.png)

TO PARAPHRASE KARL MARX, feminist silent film comedy stars appear twice: first as farce, then as tragedy — because we forget them. Hilarious pranksters who deploy comical violence to subvert stultifying gender norms have long been overshadowed in the film canon by male clowns like Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, and Max Linder. “I’m astonished that people seem to think that Chaplin invented silent comedy,” remarks Elif Rongen-Kaynakçi, silent film curator at the EYE Film Institute in Amsterdam. “By the time [Chaplin] started in 1914, many others [including women] already had their own comic series.” Fandom today is the basis for making all sorts of curatorial decisions: what to preserve, what to restore/digitize, and what to abandon to time and decay. For this reason, there’s been an ongoing feminist movement of archival activism to remake the film canon.

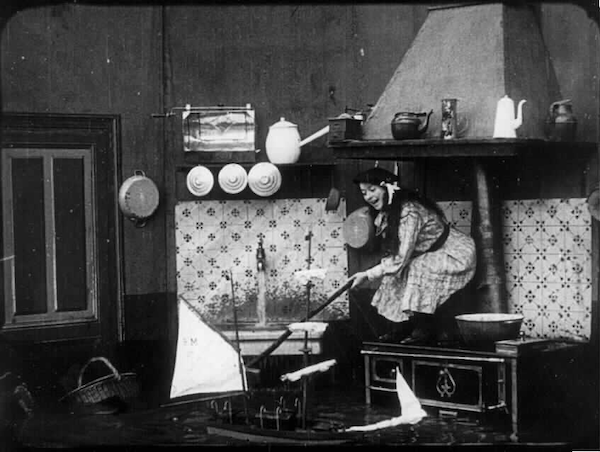

In that spirit, in 2017 at Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, Laura Horak and I curated our first silent film program on “Nasty Women” of the suffragette era: catastrophic kitchen maids, cross-dressing cowgirls, and dissident anarchists all figured prominently in the festivities, and will again in our second installment of the series this month. The term “nasty woman” became a feminist rallying cry in 2016, when Donald Trump uttered it as a slur during a presidential debate (and more recently in reference to the Danish prime minister, Mette Frederiksen). “The films in our Nasty Women program,” says Horak (associate professor at Carleton University), “show that there is a long tradition of women acting out and refusing the wide variety of constraints that are placed on them, from body-squeezing corsets, to good manners, to sexual harassment in the workplace, and even to gravity.” For example, an Irish maid named Bridget McKeen explodes out of the chimney, Lea Giunchi tyrannizes the Italian military, a pregnant lady (directed by Alice Guy-Blaché — subject of the recent documentary Be Natural) goes on an oral rampage with her maternity cravings, and a black woman named Mandy (Bertha Regustus) spreads her contagious laughter to the church, the police force, and the white working class. Nastiness was an occupational hazard of being a woman during a socially transformative era. But it was also a weapon for feminist activism and joyful protest.

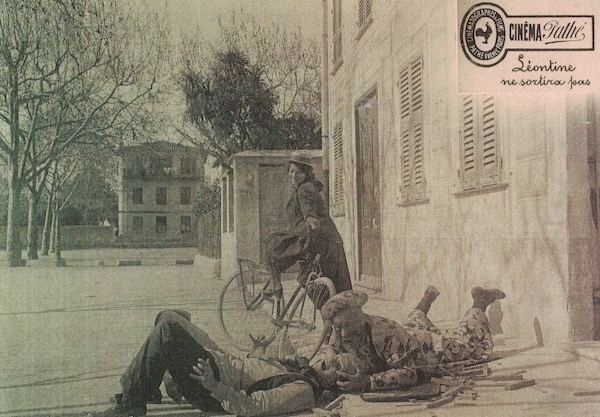

One nasty woman who I will never forget is Léontine. She is an anarchic force of nature, a teenage prankster who takes outrageous delight in her devilish schemes, and a sadist who would give Eric Cartman and Stewie Griffin a run for their money. But the screen actress who played her remains unknown, unidentified, a ghost of film history. Mariann Lewinsky, film curator at the Cineteca di Bologna and mastermind of the must-watch DVD “Comic Actresses and Suffragettes,” once recalled spotting her as an extra in a 1916 French comedy, but she was unable to remember the title. I’ve consulted scores of slapstick historians and aficionados — Steve Massa, Bryony Dixon, Ben Model, Jay Weissberg, Richard Abel, Kristen Anderson Wagner, Donald Crafton, Tom Gunning, Rob King, Joanna Rapf — but no one can identify her.

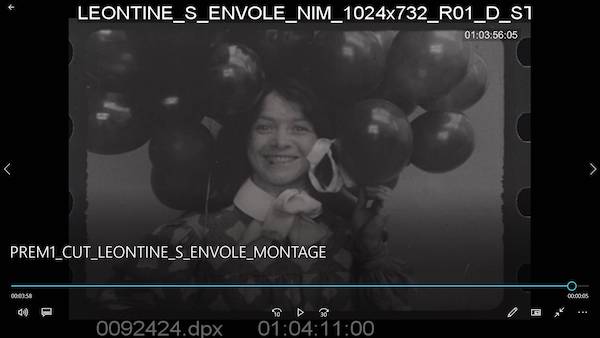

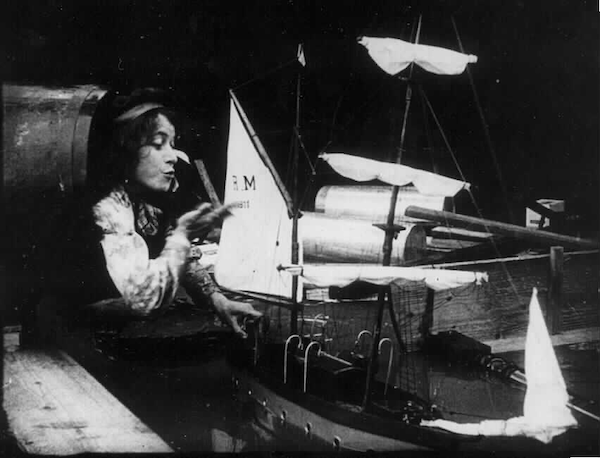

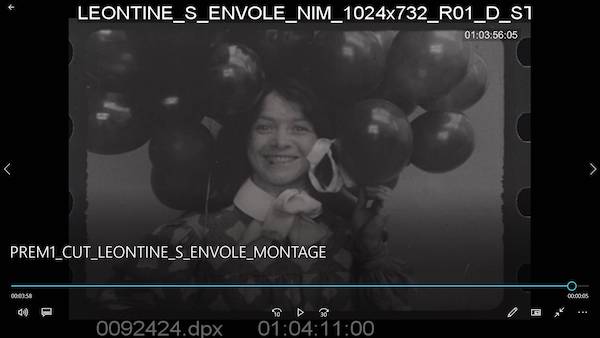

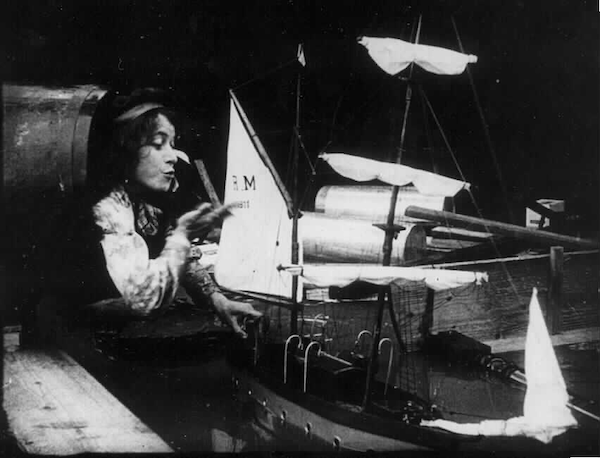

Nicknamed “Titine” in France (“Betty” in the United States), she starred in about 22 episodes of her own comic film series, produced by Pathé-Frères from 1910 to 1912. In one film, Titine floods her home with water because the bathtub isn’t large enough for her to sail her toy boat. In another, she compels people to perform a crazy jitterbug dance by electrocuting them with her high voltage battery. Ever on the run from the law, she escapes punishment by attaching 50 balloons to her head and flying away in Léontine Flies Away (1911). But her definitive weapon of choice is a piece of string, which she wields to the torment of all others — from mild pranks involving knotted shoelaces to morbid gallows humor where the joke itself hangs by a noose.

When I watch Titine’s films, her maniacal gleam taunts me, almost daring me to forget her. She is a creature who exists purely for the moment. Whether playing with fireworks, jury-rigging a high-power motor fan, wielding a decapitated wolf’s head, or simply tying people’s precious possessions to moving vehicles, she takes no account of the future. Herein lies the paradox of Léontine’s charisma: if it can’t be destroyed, then it wasn’t worth saving. Her blind faith in the apocalypse, somehow, gives me perverse hope for tomorrow.

Like Titine with her demonic string, historians have conjured unseen nitrate reels and raised the dead of previous feminist generations, revealing their overwhelming resonance for our current age — with its explosion of gender protest, defiant laughter, and unorthodox comedy. Titine laughs and destroys; meanwhile, our own laughter intermingles the urge to annihilate with the hope that something better might emerge in its wake. All of Titine’s films, in essence, are about the apocalyptic demolition of a world that one no longer wants to inhabit. But like a true sailor of toy boats in flooded domiciles, Titine goes down with the ship.

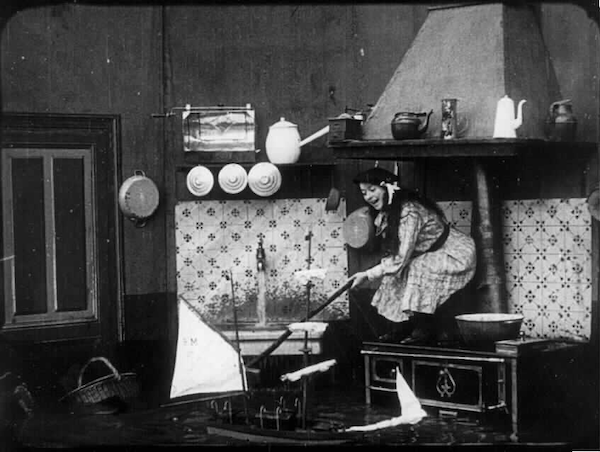

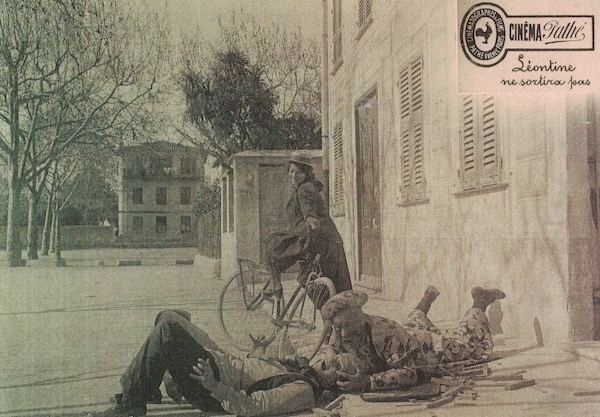

It’s fitting, then, in a way, that so little would survive of Titine’s own filmography. In the first episodes of the series (from summer of 1910), the farce is very broad: she knocks over a vegetable stand and a café table, she crashes a bicycle into an artist’s kiosk and demolishes his masterpiece, she plays with fireworks and torches two elegant ladies, and so forth. Meanwhile, the angry lynch mob gathers behind her, bloodthirsty to dole out punishment. By the end of the series, however, her antics are much darker, more demonic, and display an all-consuming drive for blanket destruction rather than a playful sense of reckless abandon. In the final episode, Léontine Guards the House (released January 1912), she strangles a little girl with a jump rope in a fit of anger, abandons her baby brother alone in a public park, and then simultaneously floods and incinerates her family home. The series concludes not with madcap anarchy but with apocalyptic nihilism: society is no longer livable for an impish malcontent like Titine. She cannot be disciplined or corrected — she lives to destroy, and that is the basis of her liveliness.

Like Léontine’s apocalyptic escapades, the film-historical archive is marked by the violence of erasure. But not all violence is created equal — Titine’s gags are cathartic, while archival wreckage is tragic. Between 75 percent and 90 percent of all silent films are now lost forever, depending on who you ask. It’s a vicious circle: the works that survive shape our memory of film history, but they were prioritized for preservation in the first place because they conformed to certain ideals of cultural heritage and national identity. Girish Shambu has thus called for a “new cinephilia.” “The old cinephilia is the cinephilia that has dominated film culture for [at least] the last seventy-five years,” while the “new cinephilia,” in contrast, goes beyond mere aesthetic experience to stir up “a deep curiosity about the world and a critical engagement with it.” Archival research is vital to this movement — to dig up unseen fragments of contested film history and reveal how the past already was other than we’ve been led to imagine it. That means “the things we take for granted now,” Horak adds, “can be different in the future.”

There’s a long legacy of feminist labor and commitment behind these recent efforts, exemplified by the “Women Film Pioneers Project,” a silent film database founded by Jane Gaines at Columbia University; Jennifer Bean and Diane Negra’s crucial volume, A Feminist Reader in Early Cinema; and Shelley Stamp’s tireless advocacy, with her founding of the journal Feminist Media Histories and production of Pioneers: First Women Filmmakers, a DVD/Blu-ray set that compiles over 1,710-minutes of forgotten feminist filmmaking. “People don’t realize,” Horak observes, “how central the experiences, concerns, and frustrations of women were to early cinema.” Jacqueline Stewart, who’s done more than anyone to exhibit overlooked African-American screen archives, recently “made history” by becoming Turner Classic Movies’s first black film host of “Sunday Night Silents.” The excitement of archival discovery is further evinced by the active web communities that have rallied around it (Silent London, Movies Silently, The Cinephiliacs, Domitor) and retrospective festivals that are instrumental to revivifying it (Pordenone, Bologna, San Francisco, Britain, Mexico, and elsewhere).

Despite this plenitude of resources, the missing pieces continue to haunt me. Lost films such as The Servant’s Revenge, The Kitchen Maid’s Dream, How They Got the Vote, and The Suffragette Sheriff remain unknowable secrets: suggestive titles, supplemented by archival fragments, that might miraculously resurface on nitrate in a private collector’s basement or under an abandoned hockey rink in the Yukon. It’s highly improbable, but not without precedent. Have you seen Bill Morrison’s Dawson City: Frozen Time? Horak says that if she could save only one lost silent film, it would be The Cowboys and the Bachelor Girls (1910), “where a group of Vassar women take over a Western ranch and run it ‘à la suffragette fashion.’” Or maybe The Crystal Cup (1927), “where a swaggering suit-clad Dorothy Mackaill swears off all men, making reviewers think of the scandalous lesbian play on Broadway at the time, The Captive.” For me, it’s The Kitchen Maid’s Dream (1907), a trick film about an overtired domestic who fantasizes that she can dismember her own limbs to finish her chores on time while the rest of her (dismembered?) body relaxes. Housework, like archival research, can be extremely tedious and time-consuming. Absurd comedies from over a century ago about exhausted women who defy their lot by embodying the radical powers of cinema, it’s no wonder, capture the hearts and minds of feminist academics. It gives us hope that countless hours of diligent labor and intellectual concentration can yield sudden, transformative ends.

There’s plenty of reason to be optimistic that even a ghost like Titine will one day reveal herself. More than half of her films still exist on celluloid in a handful of film archives, and Laura and I are working on digitizing them for a “Nasty Women”–themed DVD set. Yet, I still have absolutely no clue as to her identity — and I’ve looked everywhere. At the Gaumont-Pathé Archives, Bibliothèque nationale, and the Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé; in trade papers and magazines — such as The Moving Picture World, Ciné-Journal, and Bulletin Pathé — where her films were frequently advertised; and have sifted through the digital triumvirate for any silent film historian: Lantern, Gallica, and the Pathé Fondation. Ever a specter, she evades my grasp, like those of her pursuers whom she tormented with string. I’m not alone in my obsession with Titine. “It won’t be an exaggeration,” film critic Anuj Malhotra once told me, “to claim that the films with Betty/Leontine are some of the most spectacular discoveries of my life as a cinephile.” The 2019 “Nasty Women” program features new digital restorations of several coveted Titine titles, among an expanded cohort of feminist rabble-rousers and catastrophic kitchen maids.

Titine is the “Holy Grail” of feminist film archiving, proclaimed Rongen-Kaynakçi. She recently unearthed the identity — or at least the stage name — of another popular comedic character, Cunégonde, who appeared in over 20 episodes of a series produced by the Lux Company from 1911 to 1913. In many ways, she is the mysterious Titine’s mirror image, an archival conundrum miraculously solved. Unlike Titine, however, who played the same character in every film — messy braids, loose-fitting checked dress, dark knee socks, tomboy athleticism, and devilish grin — Cunégonde assumes various guises. She’s a frumpy housemaid, a jealous wife, a shape-shifting magician, an accidental umbrella tycoon, and even a chic “femme du monde.” But there’s no question that Cunégonde was, above all, a “nasty woman” — her name itself a pun on the French and Latin terms for vagina and a nod to Candide’s incestuous affection for his cousin in Voltaire’s novella.

Cunégonde’s abject antics provoke exuberant hilarity into the present day. How many comedies from 2012, let alone from 1912, hold up so well beyond the expiration of their topical relevance or social immediacy? “For at least 10 years,” admitted Rongen-Kaynakçi, “I’d thought this was a lost cause. In the end, thanks to the digitized libraries, databases and archives such as Lantern, Gallica, et cetera, I could gather enough leads and evidence.” Rongen-Kaynakçi first tested her theory at the “Mostly Lost: Film Identification Workshop” in Culpeper, Virginia, in 2018, which generated more clues, information, attention, and excitement.

Now that we know who Little Chrysia was, we find her everywhere — in addition to Cunégonde, she played Zoë (Pathé Nizza/Comica), who was known as Alma in Germany, and later adapted into Caroline for the United Kingdom, where Little Chrysia also starred as Arabella, a reboot of Cunégonde that harkened back to her zany music hall performances on the French Riviera before beginning her career as a screen actress. The trails of evidence — leading us from the Théâtre Cluny in 1907 Paris, along her traveling circus route, to a British wartime slapstick series — help us see “the bigger picture,” which Rongen-Kaynakçi describes as “the gray zone between the music hall and cinema, the popular entertainment culture before World War I, and how these performers were moving from one country to the other, from one production company to the other, or from one character to another.”

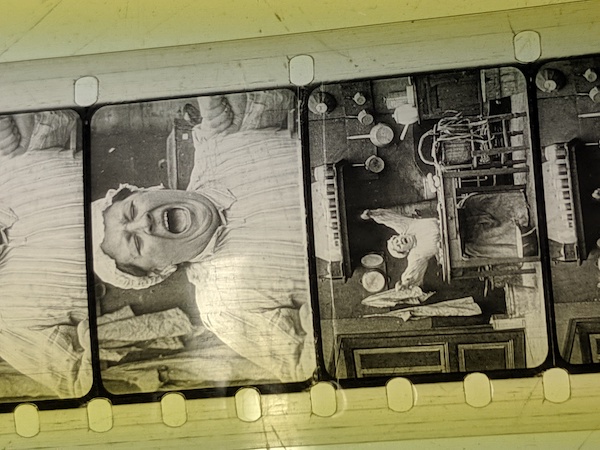

Meanwhile, I play hide-and-seek with Titine’s specter from nitrate reels to national archives to digital search engines. Last summer at the EYE, Rongen-Kaynakçi and I caught a glimmer of Titine on the unusually gauged-28mm print of Rosalie Has Sleeping Sickness. (The EYE holds half-a-dozen Léontine titles in their Desmet Collection.) Titine often appeared alongside her pal Rosalie, played by the legendary slapstick hellcat Sarah Duhamel — who has the robust agility of Melissa McCarthy and steely deadpan of Aubrey Plaza. The duo also raises Cain together in Léontine and Rosalie Go to the Theater, Rosalie and Her Phonograph, and Disastrous Cleaning Day, where they give their tenants a sneak preview of the trenches at the Marne by attempting to renovate a house on very short notice. In the film we viewed — eyeballing it frame by frame because we didn’t have a 28mm projector — Duhamel plays an overtired housemaid, who sleeps through an escalation of voluble attempts to rouse her. Titine shows up briefly in Rosalie’s bedroom banging a cooking pan, and later returns with a bucket of water.

Among the abundance of archival artifacts, most materials don’t make the cut. Stéphanie Salmon, director of Collections at the Pathé Foundation, is working on restoring their Titine films from nitrate copies (they have about 10 different titles). Salmon commented that their decision to prioritize Léontine above other worthy candidates stems from “new public interest” in the topic of gender and comedy. With the international explosion of feminist laughter today — from Hannah Gadsby and Mindy Kaling to Ali Wong and Issa Rae — it’s unsurprising that lovers of film are equally excited to find precedents in the archive for what strikes them as sheer novelty, singular to our own cultural moment. “I was totally shocked by how explicit the gay and lesbian innuendo was in these old films,” confesses Horak — who has written an award-winning book on the topic — and by “how rich and surprising the roles of cross-dressing women were.”

As an avid fan of the feminist comedy firmament today, and a cinephile of the silent film archive, I’m always tickled by the uproarious enjoyment that Titine, Rosalie, and Cunégonde continue to provoke, as do their cohort of catastrophic “nasty women” — Lea, Tilly, Sally, Mabel, Mme Plumette, Daisy Doodad, and too many others to name. I’ve shared these films with my students at the University of Minnesota, programmed them at screenings and festivals — everywhere from Italy to Ithaca, and Minneapolis to Mexico — but take even greater pleasure in the irate reactions of the haters and skeptics. It was at one of our “Nasty Women” screenings in 2017, in Pordenone’s magisterial Teatro Verdi, where I overheard a disgruntled spectator mutter aloud — first under his breath, then louder and louder: “She’s not funny, she’s just nasty!” Mission accomplished.

I would like to thank Annie Berke and Kyle Stevens for their invaluable feedback on multiple drafts of this article.

Maggie Hennefeld is assistant professor of cultural studies and comparative literature at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. She is author of Specters of Slapstick and Silent Film Comediennes, co-editor of Unwatchable, and editor of the journal Cultural Critique.

In that spirit, in 2017 at Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, Laura Horak and I curated our first silent film program on “Nasty Women” of the suffragette era: catastrophic kitchen maids, cross-dressing cowgirls, and dissident anarchists all figured prominently in the festivities, and will again in our second installment of the series this month. The term “nasty woman” became a feminist rallying cry in 2016, when Donald Trump uttered it as a slur during a presidential debate (and more recently in reference to the Danish prime minister, Mette Frederiksen). “The films in our Nasty Women program,” says Horak (associate professor at Carleton University), “show that there is a long tradition of women acting out and refusing the wide variety of constraints that are placed on them, from body-squeezing corsets, to good manners, to sexual harassment in the workplace, and even to gravity.” For example, an Irish maid named Bridget McKeen explodes out of the chimney, Lea Giunchi tyrannizes the Italian military, a pregnant lady (directed by Alice Guy-Blaché — subject of the recent documentary Be Natural) goes on an oral rampage with her maternity cravings, and a black woman named Mandy (Bertha Regustus) spreads her contagious laughter to the church, the police force, and the white working class. Nastiness was an occupational hazard of being a woman during a socially transformative era. But it was also a weapon for feminist activism and joyful protest.

One nasty woman who I will never forget is Léontine. She is an anarchic force of nature, a teenage prankster who takes outrageous delight in her devilish schemes, and a sadist who would give Eric Cartman and Stewie Griffin a run for their money. But the screen actress who played her remains unknown, unidentified, a ghost of film history. Mariann Lewinsky, film curator at the Cineteca di Bologna and mastermind of the must-watch DVD “Comic Actresses and Suffragettes,” once recalled spotting her as an extra in a 1916 French comedy, but she was unable to remember the title. I’ve consulted scores of slapstick historians and aficionados — Steve Massa, Bryony Dixon, Ben Model, Jay Weissberg, Richard Abel, Kristen Anderson Wagner, Donald Crafton, Tom Gunning, Rob King, Joanna Rapf — but no one can identify her.

¤

Nicknamed “Titine” in France (“Betty” in the United States), she starred in about 22 episodes of her own comic film series, produced by Pathé-Frères from 1910 to 1912. In one film, Titine floods her home with water because the bathtub isn’t large enough for her to sail her toy boat. In another, she compels people to perform a crazy jitterbug dance by electrocuting them with her high voltage battery. Ever on the run from the law, she escapes punishment by attaching 50 balloons to her head and flying away in Léontine Flies Away (1911). But her definitive weapon of choice is a piece of string, which she wields to the torment of all others — from mild pranks involving knotted shoelaces to morbid gallows humor where the joke itself hangs by a noose.

When I watch Titine’s films, her maniacal gleam taunts me, almost daring me to forget her. She is a creature who exists purely for the moment. Whether playing with fireworks, jury-rigging a high-power motor fan, wielding a decapitated wolf’s head, or simply tying people’s precious possessions to moving vehicles, she takes no account of the future. Herein lies the paradox of Léontine’s charisma: if it can’t be destroyed, then it wasn’t worth saving. Her blind faith in the apocalypse, somehow, gives me perverse hope for tomorrow.

Like Titine with her demonic string, historians have conjured unseen nitrate reels and raised the dead of previous feminist generations, revealing their overwhelming resonance for our current age — with its explosion of gender protest, defiant laughter, and unorthodox comedy. Titine laughs and destroys; meanwhile, our own laughter intermingles the urge to annihilate with the hope that something better might emerge in its wake. All of Titine’s films, in essence, are about the apocalyptic demolition of a world that one no longer wants to inhabit. But like a true sailor of toy boats in flooded domiciles, Titine goes down with the ship.

It’s fitting, then, in a way, that so little would survive of Titine’s own filmography. In the first episodes of the series (from summer of 1910), the farce is very broad: she knocks over a vegetable stand and a café table, she crashes a bicycle into an artist’s kiosk and demolishes his masterpiece, she plays with fireworks and torches two elegant ladies, and so forth. Meanwhile, the angry lynch mob gathers behind her, bloodthirsty to dole out punishment. By the end of the series, however, her antics are much darker, more demonic, and display an all-consuming drive for blanket destruction rather than a playful sense of reckless abandon. In the final episode, Léontine Guards the House (released January 1912), she strangles a little girl with a jump rope in a fit of anger, abandons her baby brother alone in a public park, and then simultaneously floods and incinerates her family home. The series concludes not with madcap anarchy but with apocalyptic nihilism: society is no longer livable for an impish malcontent like Titine. She cannot be disciplined or corrected — she lives to destroy, and that is the basis of her liveliness.

Like Léontine’s apocalyptic escapades, the film-historical archive is marked by the violence of erasure. But not all violence is created equal — Titine’s gags are cathartic, while archival wreckage is tragic. Between 75 percent and 90 percent of all silent films are now lost forever, depending on who you ask. It’s a vicious circle: the works that survive shape our memory of film history, but they were prioritized for preservation in the first place because they conformed to certain ideals of cultural heritage and national identity. Girish Shambu has thus called for a “new cinephilia.” “The old cinephilia is the cinephilia that has dominated film culture for [at least] the last seventy-five years,” while the “new cinephilia,” in contrast, goes beyond mere aesthetic experience to stir up “a deep curiosity about the world and a critical engagement with it.” Archival research is vital to this movement — to dig up unseen fragments of contested film history and reveal how the past already was other than we’ve been led to imagine it. That means “the things we take for granted now,” Horak adds, “can be different in the future.”

¤

There’s a long legacy of feminist labor and commitment behind these recent efforts, exemplified by the “Women Film Pioneers Project,” a silent film database founded by Jane Gaines at Columbia University; Jennifer Bean and Diane Negra’s crucial volume, A Feminist Reader in Early Cinema; and Shelley Stamp’s tireless advocacy, with her founding of the journal Feminist Media Histories and production of Pioneers: First Women Filmmakers, a DVD/Blu-ray set that compiles over 1,710-minutes of forgotten feminist filmmaking. “People don’t realize,” Horak observes, “how central the experiences, concerns, and frustrations of women were to early cinema.” Jacqueline Stewart, who’s done more than anyone to exhibit overlooked African-American screen archives, recently “made history” by becoming Turner Classic Movies’s first black film host of “Sunday Night Silents.” The excitement of archival discovery is further evinced by the active web communities that have rallied around it (Silent London, Movies Silently, The Cinephiliacs, Domitor) and retrospective festivals that are instrumental to revivifying it (Pordenone, Bologna, San Francisco, Britain, Mexico, and elsewhere).

Despite this plenitude of resources, the missing pieces continue to haunt me. Lost films such as The Servant’s Revenge, The Kitchen Maid’s Dream, How They Got the Vote, and The Suffragette Sheriff remain unknowable secrets: suggestive titles, supplemented by archival fragments, that might miraculously resurface on nitrate in a private collector’s basement or under an abandoned hockey rink in the Yukon. It’s highly improbable, but not without precedent. Have you seen Bill Morrison’s Dawson City: Frozen Time? Horak says that if she could save only one lost silent film, it would be The Cowboys and the Bachelor Girls (1910), “where a group of Vassar women take over a Western ranch and run it ‘à la suffragette fashion.’” Or maybe The Crystal Cup (1927), “where a swaggering suit-clad Dorothy Mackaill swears off all men, making reviewers think of the scandalous lesbian play on Broadway at the time, The Captive.” For me, it’s The Kitchen Maid’s Dream (1907), a trick film about an overtired domestic who fantasizes that she can dismember her own limbs to finish her chores on time while the rest of her (dismembered?) body relaxes. Housework, like archival research, can be extremely tedious and time-consuming. Absurd comedies from over a century ago about exhausted women who defy their lot by embodying the radical powers of cinema, it’s no wonder, capture the hearts and minds of feminist academics. It gives us hope that countless hours of diligent labor and intellectual concentration can yield sudden, transformative ends.

¤

There’s plenty of reason to be optimistic that even a ghost like Titine will one day reveal herself. More than half of her films still exist on celluloid in a handful of film archives, and Laura and I are working on digitizing them for a “Nasty Women”–themed DVD set. Yet, I still have absolutely no clue as to her identity — and I’ve looked everywhere. At the Gaumont-Pathé Archives, Bibliothèque nationale, and the Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé; in trade papers and magazines — such as The Moving Picture World, Ciné-Journal, and Bulletin Pathé — where her films were frequently advertised; and have sifted through the digital triumvirate for any silent film historian: Lantern, Gallica, and the Pathé Fondation. Ever a specter, she evades my grasp, like those of her pursuers whom she tormented with string. I’m not alone in my obsession with Titine. “It won’t be an exaggeration,” film critic Anuj Malhotra once told me, “to claim that the films with Betty/Leontine are some of the most spectacular discoveries of my life as a cinephile.” The 2019 “Nasty Women” program features new digital restorations of several coveted Titine titles, among an expanded cohort of feminist rabble-rousers and catastrophic kitchen maids.

Titine is the “Holy Grail” of feminist film archiving, proclaimed Rongen-Kaynakçi. She recently unearthed the identity — or at least the stage name — of another popular comedic character, Cunégonde, who appeared in over 20 episodes of a series produced by the Lux Company from 1911 to 1913. In many ways, she is the mysterious Titine’s mirror image, an archival conundrum miraculously solved. Unlike Titine, however, who played the same character in every film — messy braids, loose-fitting checked dress, dark knee socks, tomboy athleticism, and devilish grin — Cunégonde assumes various guises. She’s a frumpy housemaid, a jealous wife, a shape-shifting magician, an accidental umbrella tycoon, and even a chic “femme du monde.” But there’s no question that Cunégonde was, above all, a “nasty woman” — her name itself a pun on the French and Latin terms for vagina and a nod to Candide’s incestuous affection for his cousin in Voltaire’s novella.

Cunégonde’s abject antics provoke exuberant hilarity into the present day. How many comedies from 2012, let alone from 1912, hold up so well beyond the expiration of their topical relevance or social immediacy? “For at least 10 years,” admitted Rongen-Kaynakçi, “I’d thought this was a lost cause. In the end, thanks to the digitized libraries, databases and archives such as Lantern, Gallica, et cetera, I could gather enough leads and evidence.” Rongen-Kaynakçi first tested her theory at the “Mostly Lost: Film Identification Workshop” in Culpeper, Virginia, in 2018, which generated more clues, information, attention, and excitement.

Now that we know who Little Chrysia was, we find her everywhere — in addition to Cunégonde, she played Zoë (Pathé Nizza/Comica), who was known as Alma in Germany, and later adapted into Caroline for the United Kingdom, where Little Chrysia also starred as Arabella, a reboot of Cunégonde that harkened back to her zany music hall performances on the French Riviera before beginning her career as a screen actress. The trails of evidence — leading us from the Théâtre Cluny in 1907 Paris, along her traveling circus route, to a British wartime slapstick series — help us see “the bigger picture,” which Rongen-Kaynakçi describes as “the gray zone between the music hall and cinema, the popular entertainment culture before World War I, and how these performers were moving from one country to the other, from one production company to the other, or from one character to another.”

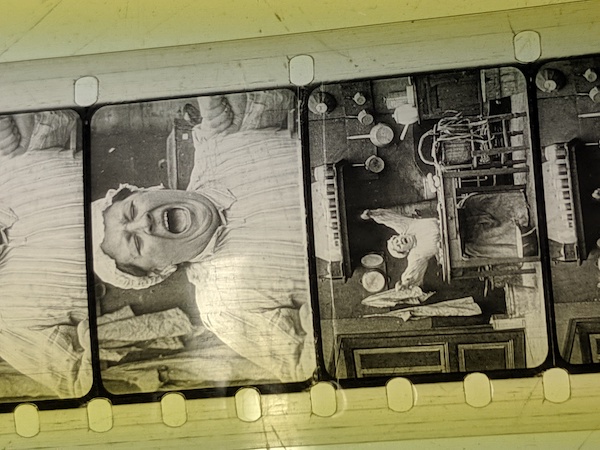

Meanwhile, I play hide-and-seek with Titine’s specter from nitrate reels to national archives to digital search engines. Last summer at the EYE, Rongen-Kaynakçi and I caught a glimmer of Titine on the unusually gauged-28mm print of Rosalie Has Sleeping Sickness. (The EYE holds half-a-dozen Léontine titles in their Desmet Collection.) Titine often appeared alongside her pal Rosalie, played by the legendary slapstick hellcat Sarah Duhamel — who has the robust agility of Melissa McCarthy and steely deadpan of Aubrey Plaza. The duo also raises Cain together in Léontine and Rosalie Go to the Theater, Rosalie and Her Phonograph, and Disastrous Cleaning Day, where they give their tenants a sneak preview of the trenches at the Marne by attempting to renovate a house on very short notice. In the film we viewed — eyeballing it frame by frame because we didn’t have a 28mm projector — Duhamel plays an overtired housemaid, who sleeps through an escalation of voluble attempts to rouse her. Titine shows up briefly in Rosalie’s bedroom banging a cooking pan, and later returns with a bucket of water.

Among the abundance of archival artifacts, most materials don’t make the cut. Stéphanie Salmon, director of Collections at the Pathé Foundation, is working on restoring their Titine films from nitrate copies (they have about 10 different titles). Salmon commented that their decision to prioritize Léontine above other worthy candidates stems from “new public interest” in the topic of gender and comedy. With the international explosion of feminist laughter today — from Hannah Gadsby and Mindy Kaling to Ali Wong and Issa Rae — it’s unsurprising that lovers of film are equally excited to find precedents in the archive for what strikes them as sheer novelty, singular to our own cultural moment. “I was totally shocked by how explicit the gay and lesbian innuendo was in these old films,” confesses Horak — who has written an award-winning book on the topic — and by “how rich and surprising the roles of cross-dressing women were.”

As an avid fan of the feminist comedy firmament today, and a cinephile of the silent film archive, I’m always tickled by the uproarious enjoyment that Titine, Rosalie, and Cunégonde continue to provoke, as do their cohort of catastrophic “nasty women” — Lea, Tilly, Sally, Mabel, Mme Plumette, Daisy Doodad, and too many others to name. I’ve shared these films with my students at the University of Minnesota, programmed them at screenings and festivals — everywhere from Italy to Ithaca, and Minneapolis to Mexico — but take even greater pleasure in the irate reactions of the haters and skeptics. It was at one of our “Nasty Women” screenings in 2017, in Pordenone’s magisterial Teatro Verdi, where I overheard a disgruntled spectator mutter aloud — first under his breath, then louder and louder: “She’s not funny, she’s just nasty!” Mission accomplished.

¤

I would like to thank Annie Berke and Kyle Stevens for their invaluable feedback on multiple drafts of this article.

¤

Maggie Hennefeld is assistant professor of cultural studies and comparative literature at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. She is author of Specters of Slapstick and Silent Film Comediennes, co-editor of Unwatchable, and editor of the journal Cultural Critique.

LARB Contributor

Maggie Hennefeld is McKnight Presidential Fellow and associate professor of cultural studies and comparative literature at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. She is author of the award-winning Specters of Slapstick and Silent Film Comediennes (Columbia University Press, 2018), and co-editor of Cultural Critique and of two volumes, Unwatchable (Rutgers University Press, 2019) and Abjection Incorporated: Mediating the Politics of Pleasure and Violence (Duke University Press, 2020).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Bewitched by “Olivia”

Kyle Stevens considers the 1951 film “Olivia,” an obscure queer classic from an under-appreciated.

An Actor Lost in the Background

Andrew Fedorov considers the legacy of prolific Hollywood extra Robert G. Haines.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!