This piece will appear in the LARB Print Quarterly Journal: No. 15, Revolution

Become a member to receive the LARB Quarterly Journal

I SAW SOMETHING on my left cheek. I thought it was a scab. I pulled it off. It was a tick. Less than a 10th of an inch and very light in color, it was a taupe little thing, not big and black like the tick I found on my back just a month ago. I live in Nashville much the way my mother lived in Atlanta, but without her beauty or luxury. As a child, I was in awe of the woman who laughed or screamed at me. She shunned me, but now, dead, she stays close. Sometimes she comes down the wall like a spider.

For years I’ve been writing her story. I tried in vain to forget her, but she stays around as close to me as my breath. No death counts if the feeling is strong enough.

After she died, boxes arrived from Atlanta. They filled the garage. I gave away her clothes: furs, gowns, sequined sashes, golf shoes, and hats. But I kept my father’s photos of her. There were thousands. One had been corroded by water. This photo of my mother just after her marriage shades from pale lilac to ochre to yellow to cobalt blue to gray, as if cinders were eating away at the remnants of color. Her lineaments curve gently in and out of the mold. What shows is one eye, an immaculately plucked brow, a bit of hair covered with something like a hat but more like a towel, pulled down with her hands caught mid-movement. The rest of the body is a blur of fabric dissolved into the waste of wet and dust.

Looking through other photos of my mother, I am not sure how to tell who she was or where she came from. Everything seems make-believe. She told me she was from Paris. Years later, in a taxi going to a restaurant in New York, she began speaking Creole to the driver. She smiled and told me she was Haitian. In trying to tell her story and account for my discomfiture in the world of humans, words like mimicry and falsity come to mind. I always felt that I was not right in my skin. Everything had to do with race. What mattered most was the quality of hair, the color of skin. She called me “Ubangi.” I did not look like her friends’ daughters. She did not like me to touch her.

But who was she? As I write this, I remember how she hated to be referred to as “she” or “her.” “I have a name,” she would say. But even that was a changeable thing. Her real name was Sophie. She never uttered it, changing it occasionally to “Sophia,” but most often going by the name her friends gave her when she arrived in Atlanta, still speaking French. They called her “Frenchie.” Like her appearance, her name was mutable, adapted to whatever role was demanded, no matter how fantastic.

Appearance was everything. I tried in vain to tell the difference between fantasy and reality.

My mother left Haiti two years after the American occupation ended, moving with her family to Brooklyn, where she met my father and soon married him. When the US marines finally departed in 1934, Haitians sang words in praise of President Sténio Vincent that my mother later sang to me — but only after my father died. “If there’s anyone who loves the people, it’s President Vincent,” and she sang it to me in Creole: “Papa Vincent, mesi. Si gen youn moun ki renmen pèp la, se President Vincent.” In a deep and rapturous voice, she gave thanks for all he, “a mulatto” as he was called at the time, did for the blacks of Haiti, while ruthlessly punishing light-skinned elites. With this one song, she let me in on her secret: she harbored a confounding infidelity to her class and color.

This light-skinned woman, daughter of a Syrian merchant, belted out a couple of lines of the popular merengue recorded by Alan Lomax, who heard it at the elite Club Toland in Port-au-Prince on Christmas Eve, 1936: “This is a guy who loves the people / This is the guy who gives us the right to sell in the streets / He gives us that because he kicked out the Syrians / So we’re crying out, thank you Papa Vincent.” The self-proclaimed “Second Liberator” allowed the masses to sell goods wherever they could, and curbed the Syrian takeover of retail, shuttering their stores and driving them out.

That same year, my mother traveled from Brooklyn to a honeymoon in Mexico, where she and my father traveled around for two years, then to Nashville, and, finally, to Atlanta. The South must have seemed to her like a cross between Haiti and New York. “I would have been an actress,” she told me. “Then I met your father.” But she never stopped acting. She lived to be looked at.

After leaving Haiti at the age of 13, my mother never knew beauty or hope again. Everything that followed her departure and her marriage at 17 to a 37-year-old husband seemed useless or dead. When she moved with my father to the Jim Crow South, she exchanged her complex racial origins for the empty costume of white-washed glamour. I didn’t realize until now, as I write, just how deluded she was about her real attachments, and just how casually — without really ever knowing the loss — she surrendered her origins to a mask of whiteness.

But in moments of privacy, when not seen by the eyes of others, she used to say things that sounded like incantations. “Arab manje koulèv,” which in Creole means “Arabs eat snakes.” She was never clear about her family or her childhood, explaining that her father told her not to worry about his origins. “It’s no good to be too strange in a country you love,” he sighed. They never meant anything to me at the time, those words said in the dark of my bedroom.

Years later, I learned they were pieces of the life she had left behind, not just rapt conjuring. Besides “Mesi, Papa Vincent,” she repeated, “Desalin pas vle oue blanc,” which means “Dessalines doesn’t like whites.” Late at night when she came into my room, she returned to the beauty and force of her life in Haiti.

Her longing was consecrated most often in this homage to Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who proclaimed Haitian independence in 1804. She praised only the fierce Dessalines — called “barbaric” by most historians — not the urbane Toussaint l’Ouverture or Henri Christophe, who was turned into a god or spirit by the Haitian people. He is still invoked as a lwa in vodou ceremonies in the countryside. Rejecting things French and unconcerned about social graces, he fought to give land to ex-slaves who had only recently been considered property themselves.

In the South, my mother concealed her past, even as she remained estranged from the whites around her. By the time my mother got to Nashville, she recognized the necessity to become as white as possible. A gilded white lady of the South, that’s what my father wanted. Confined by the role she assumed, she performed her new identity. Hiding herself beneath a false smile and pale skin, she wrapped her discomfort and later her sorrow in silks and jewels. This denial of her history was not anything like a power grab for white power and privilege, but rather a casual act performed in exchange for a lifestyle of luxury. This false if stylish veneer killed her spirit and destroyed any chance for happiness.

I can reckon with her life and mine only through how far I fell away from whiteness or how close I could come to black. “Who knows what evil lurks in the heart of men? The shadow knows.” We lived, my mother and I, in a world that flickered back and forth between black and white, darkness and light. Nothing could be secure.

One day she pulled a magnolia off the tree in our front yard. She grabbed it in her hand like a castanet, shook it, and pulled off the white leaves. “There,” she sighed, “There — look — and see the red and the rot.” I was astonished by the violence of that gesture and the softness of her voice. She was entranced by whatever had died and gone bad. She knew that it had once lived in beauty.

A white spider too small for me to truly make out its legs came swinging down lightly. It hovered over the pages about my mother, then two filaments came through the sunlight, now onto the desk, then around my cup of tea, then onto other pages, and now it comes toward me. So fragile and precarious that I’m afraid to move: I feel that it enveloped me in its threads. Wrung out from the innards of her being, they loop me into her life.

My mother’s past comes to me in flashes: fragments of Sinatra’s voice, the sound of laughter or the feel of her slap across my face. Her photos lead me like patches of light into a world that was but is no more. Not long after I brought them into the house, I smashed my nose against the jamb of a doorway, crushed my fingers in a broken garage door, and shattered my ribs in a fall down the stairs. We found each other again when I least expected it; and in sight of her, with her breath on my neck, I know now that whatever mattered to me, the poems I cherished, the writers I taught, and the words I wrote were inspired by her life and raised up again more fiercely after her death.

When she awakened in bed that morning in Mexico City, she looked up at my father in what seems to be sheer wonderment, or is it just languor in the soft light of a room sometime in midsummer at the beginning of their honeymoon. I had never seen any of these photos, all carefully numbered on their backs in pencil, and kept in two wooden boxes. Only now, with her death behind me, am I struck by expressions that I never saw in life, looks that astonish me in their gentle repose.

Doom is never foretold. Not when you’re young, just married to a man who adores you and takes you away to a place of sun, with dust, lizards everywhere in the cracks, birds wandering lost in streets that remind you of Port-au-Prince. She heard the familiar sounds of suffering and holiness in the bodies of beggars and priests. How bad could things be if you had a gold bracelet on your wrist given to you by a doting husband? She especially liked to see the statues of the Virgin that appeared miraculously on the steps of churches or on altars with candles, gold chalices, violets, and white carnations.

In 1939, right after their marriage, my parents arrived in Mexico. My father drove his Buick Roadmaster convertible from Guadalajara to Cuernavaca, stopping in Mexico City, traveling along roads Graham Greene first captured with his “whisky priest” in The Lawless Roads and then a year later in The Power and the Glory, but I doubt they ever read him. My father didn’t like Catholics. I do not know any details of their journey. No one ever told me stories. All that remains of the visit are photographs. They got there seven years after Hart Crane leapt off the Orizaba into the sea; eight years after Sergei Eisenstein began the film that would be cut and mangled in Hollywood; a year after Malcolm Lowry was deported, his life with the alluring Jan Gabrial a shambles.

My parents began their marriage when the New York World’s Fair opened with the debut of nylon stockings, when Billie Holiday first sang and recorded “Strange Fruit,” Judy Garland sang “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” in The Wizard of Oz, and Gone with the Wind premiered at Loew’s Grand Theater in Atlanta. Franco had just conquered Madrid, ending the Spanish Civil War. They arrived in Mexico a year before Trotsky was axed to death, at a time when over 1,000 American tourists a month visited Mexico, and artists too. None of this — no history, culture, or politics — can be gleaned from these photographs.

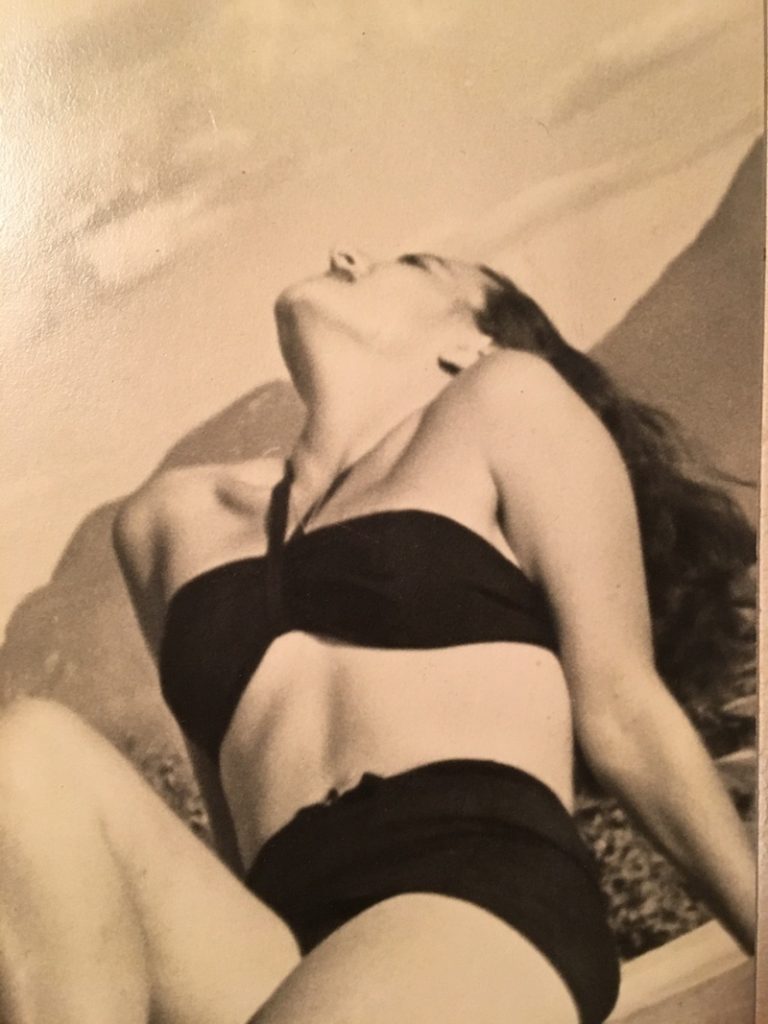

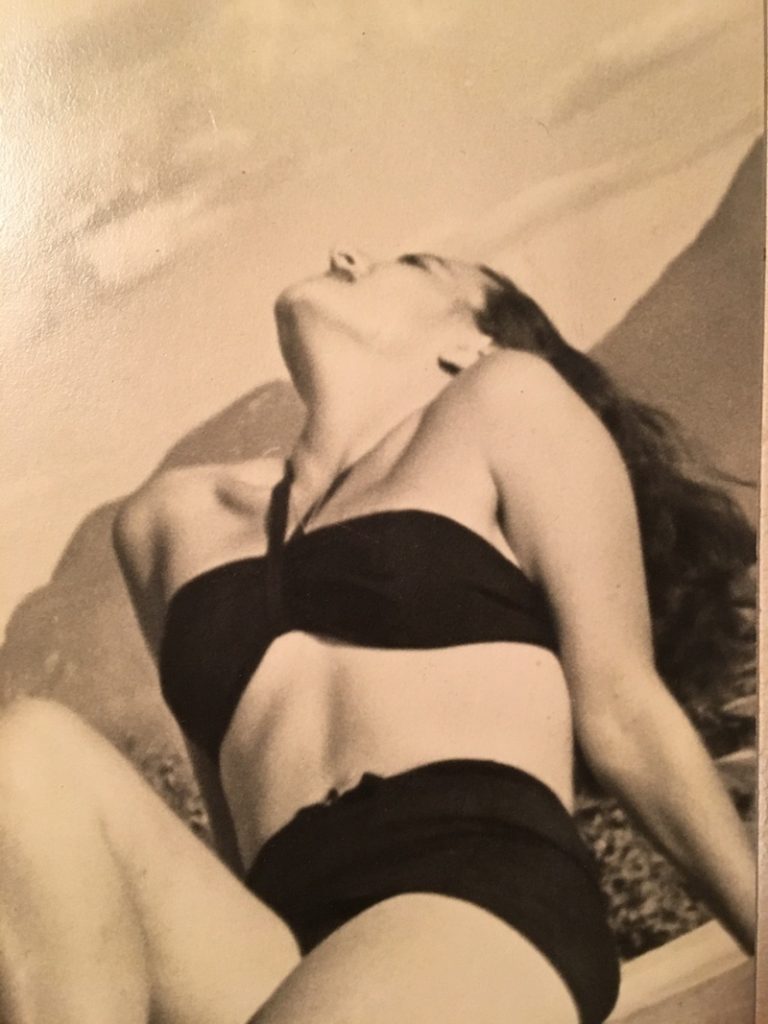

The suffering of bulls, yes, and the remarkable poses of my mother, but besides a few scenes of peasants, cacti, churches, murals, or horses, there was only a 17-year-old girl, chosen by a man 20 years older, continuously reinvented in split-second exposures, caught in hundreds of ways: lying down in a two-piece bathing suit on rocks, or sitting, long legs crossed doubly graceful in the rise of the stairs underneath her, or sometimes standing in sunlight, her head rocked to the side and eyes like tinder.

The bulls mattered to her life, even if she didn’t know it then or ever. My father went to bullfights. During those afternoons, what did my mother do? As I remember her broken life, I can’t stop thinking about the bulls, isolated from their kind, released into spectacle, performing their agony. Three quarters of a century later, I look at the pictures. Out of boxes and other wooden and steel containers, and buried deep under other albums, come these relics of a honeymoon. They were not part of anything I knew, nor did they make up any kind of beauty my parents might retrieve about a past when they might have known love or passion.

I thought these photos might tell me something about their past that would otherwise be lost forever. My mother’s face, caught in poses that were never off-guard or random, still does not speak to me. Sometimes she has that immaculate quality of being purified of anything living. When she looks out at my father, the hand drawn up on one side, sultry on the hip, I think of Rita Hayworth, her idol. The earliest films of this love goddess were on my mother’s mind when she left for Mexico with my father.

What more can be known about the honeymoon that left my mother cold, my father clueless? I’m sure that my mother never looked at any of these photos. She had no interest in remembering the past. Her indifference to what she had felt then made her the woman that I grew up knowing. I admired and feared her, but most of all I longed to be close to her, enveloped in the waves of her brown and heavy hair. Just a couple of years after marriage, the soft face of a woman beguiled became impenetrable in its exacting beauty. A veneer set in over her luscious skin, hardness seemed to take over eyes that were once inviting, her smile frozen for the camera. But that unyielding stiffness had not yet set her face in stone. She was not afraid to be vulnerable, and her eyes looked at what she thought she loved.

“Blood poured down the streets,” my mother used to repeat after my father died. Cryptic, she never explained who or what she meant. She liked to hear church bells ringing. She prayed the words she learned as a child in Port-au-Prince, where the nuns at Sacré Coeur, her school in Turgeau, took away the girls’ mirrors and then gazed secretly at themselves: “Je vous salue Marie, pleine de grâce, le seigneur est avec vous.” When she worshipped the Virgin late in life, she told me how God once loved a woman pure and without stain. Then she got confused, and remembered how hard it was to remain pure, especially when you hear stories about the djablesse, or “she-devil.” The most feared ghost in Haiti, she is condemned to walk the woods before entering heaven as punishment “for the sin of having died a virgin.” She laughed. “Think about all those nuns taught they’d go to heaven, but they end up wandering around looking for what they never got or scaring the hell out of those who have it.” With a throaty whisper, she added: “They get you coming and going.”

In Mexico her marriage began with prayers to the Virgin of Guadeloupe, our lady of the hills and patroness of the Indians and the poor, so beautiful in a blue mantle, dotted with stars; with the killing of priests, the ice-ax murder of Trotsky, my father’s hero; and a ride on a Ferris wheel that she never forgot. Each parent lost something that mattered that year in Mexico: my father, his revolution; my mother, her virginity.

She kept repeating things. Round and round, always circling back to the gold coins she threw in fountains, the stones that hit dogs, or the sun that was always too hot. Sixty years later, she recalled things I’d never heard her mention before. Not in sentences, but fragments, words thrown like skipping stones on water. “The sun burns the dust at my feet.” “Two more dogs bled, hit again with stones.” “Gold coins, I have a bracelet of coins.” Sun. Dust. Dogs. Coins. Because they never talked about their Mexico adventure, I had no idea what she meant when she called out these things at the end of her life. The photos before me bring it all back, her memories made visible.

“You remember how scared you got on our honeymoon,” my father said to my mother one day when I was a child, “how you ran from the wheel, and it just kept turning, and you never stopped running.” He said nothing more. Only now do I understand that he must have wanted his young bride to go for a ride with him on the wheel that spun in the sky.

In Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano, set on the Day of the Dead in 1938, Consul Geoffrey Firmin rides with his beloved Yvonne on “the huge looping-the-loop machine” high on the hill in the tremendous heat “in the hub of which, like a great cold eye, burned Polaris, and round and round it here they went […] they were in a dark wood.” That feeling of entrapment in time that circled on itself, ominous in its repetition, the return of a past that will not quit, reminds me of my parents’ lives. Perhaps their unhappiness was already fixed in the image of this wheel turning, not just in actuality, but also, and around the same time, in Sergei Eisenstein’s unfinished film ¡Qué Viva México!

All that remained of his visionary epic — mutilated in Hollywood — were three short features that pandered to commercial, and, some argued, fascist interests. Culled from over 200 thousand feet of film rushes, Thunder Over Mexico, Eisenstein in Mexico, and Death Day were released between the autumn of 1933 and early 1934. The last, which Lowry must have seen, features the “Dance of the Heads.” The Ferris wheel revolves dead center, while in the foreground are dancers, and hovering there are three death’s heads, human skulls, whether real or masks it does not matter: not for this story of dashed hopes, where everything seemed purposely to turn life into death, but a death more vibrant than anything life offered, in a land where stone lured more than flesh.

The dead do not die. My mother knew that the earth was squirming with spirits. At any moment she might be caught off guard. While she tangled with things too luscious to be put to rest, mostly the unseen, my father was busy using his photographic techniques to pin down patterns of light and dark, to capture brave matadors at the kill, people on the street, the campesinos in the countryside, women at market, but, most of all, his wife, transforming her into an artifact, as if her body had been raised up from rock and conceived anew in rolls of film.

In one photo he called “Sun Worshipper,” my mother stretches, head thrown back in ecstasy, hair a glossy smooth brown, one leg bent. Her body takes up most of the frame. With the mountains dwarfed behind her, she appears so fluid that she seems to recline sitting up. Years later, it won an award at the High Museum in Atlanta. I remember my father’s long nights down in the darkroom when my mother had already turned her back on him.

At no time did my father refer to their time in Mexico, though he kept and treasured a heavy wool blanket with many-colored stripes, tightly woven, with the shape of what I remember as the indigo blue, orange, and white lineaments of a face like an Aztec god. The other precious remnants of their time together were an elaborate silver water pitcher, sugar bowl, creamer, and large hand-hammered tray. As long as my parents lived, this baroque display that seemed to me heavy as lead remained in the dining room.

Become a member to receive the LARB Quarterly Journal

I SAW SOMETHING on my left cheek. I thought it was a scab. I pulled it off. It was a tick. Less than a 10th of an inch and very light in color, it was a taupe little thing, not big and black like the tick I found on my back just a month ago. I live in Nashville much the way my mother lived in Atlanta, but without her beauty or luxury. As a child, I was in awe of the woman who laughed or screamed at me. She shunned me, but now, dead, she stays close. Sometimes she comes down the wall like a spider.

For years I’ve been writing her story. I tried in vain to forget her, but she stays around as close to me as my breath. No death counts if the feeling is strong enough.

After she died, boxes arrived from Atlanta. They filled the garage. I gave away her clothes: furs, gowns, sequined sashes, golf shoes, and hats. But I kept my father’s photos of her. There were thousands. One had been corroded by water. This photo of my mother just after her marriage shades from pale lilac to ochre to yellow to cobalt blue to gray, as if cinders were eating away at the remnants of color. Her lineaments curve gently in and out of the mold. What shows is one eye, an immaculately plucked brow, a bit of hair covered with something like a hat but more like a towel, pulled down with her hands caught mid-movement. The rest of the body is a blur of fabric dissolved into the waste of wet and dust.

Looking through other photos of my mother, I am not sure how to tell who she was or where she came from. Everything seems make-believe. She told me she was from Paris. Years later, in a taxi going to a restaurant in New York, she began speaking Creole to the driver. She smiled and told me she was Haitian. In trying to tell her story and account for my discomfiture in the world of humans, words like mimicry and falsity come to mind. I always felt that I was not right in my skin. Everything had to do with race. What mattered most was the quality of hair, the color of skin. She called me “Ubangi.” I did not look like her friends’ daughters. She did not like me to touch her.

But who was she? As I write this, I remember how she hated to be referred to as “she” or “her.” “I have a name,” she would say. But even that was a changeable thing. Her real name was Sophie. She never uttered it, changing it occasionally to “Sophia,” but most often going by the name her friends gave her when she arrived in Atlanta, still speaking French. They called her “Frenchie.” Like her appearance, her name was mutable, adapted to whatever role was demanded, no matter how fantastic.

Appearance was everything. I tried in vain to tell the difference between fantasy and reality.

My mother left Haiti two years after the American occupation ended, moving with her family to Brooklyn, where she met my father and soon married him. When the US marines finally departed in 1934, Haitians sang words in praise of President Sténio Vincent that my mother later sang to me — but only after my father died. “If there’s anyone who loves the people, it’s President Vincent,” and she sang it to me in Creole: “Papa Vincent, mesi. Si gen youn moun ki renmen pèp la, se President Vincent.” In a deep and rapturous voice, she gave thanks for all he, “a mulatto” as he was called at the time, did for the blacks of Haiti, while ruthlessly punishing light-skinned elites. With this one song, she let me in on her secret: she harbored a confounding infidelity to her class and color.

This light-skinned woman, daughter of a Syrian merchant, belted out a couple of lines of the popular merengue recorded by Alan Lomax, who heard it at the elite Club Toland in Port-au-Prince on Christmas Eve, 1936: “This is a guy who loves the people / This is the guy who gives us the right to sell in the streets / He gives us that because he kicked out the Syrians / So we’re crying out, thank you Papa Vincent.” The self-proclaimed “Second Liberator” allowed the masses to sell goods wherever they could, and curbed the Syrian takeover of retail, shuttering their stores and driving them out.

That same year, my mother traveled from Brooklyn to a honeymoon in Mexico, where she and my father traveled around for two years, then to Nashville, and, finally, to Atlanta. The South must have seemed to her like a cross between Haiti and New York. “I would have been an actress,” she told me. “Then I met your father.” But she never stopped acting. She lived to be looked at.

After leaving Haiti at the age of 13, my mother never knew beauty or hope again. Everything that followed her departure and her marriage at 17 to a 37-year-old husband seemed useless or dead. When she moved with my father to the Jim Crow South, she exchanged her complex racial origins for the empty costume of white-washed glamour. I didn’t realize until now, as I write, just how deluded she was about her real attachments, and just how casually — without really ever knowing the loss — she surrendered her origins to a mask of whiteness.

But in moments of privacy, when not seen by the eyes of others, she used to say things that sounded like incantations. “Arab manje koulèv,” which in Creole means “Arabs eat snakes.” She was never clear about her family or her childhood, explaining that her father told her not to worry about his origins. “It’s no good to be too strange in a country you love,” he sighed. They never meant anything to me at the time, those words said in the dark of my bedroom.

Years later, I learned they were pieces of the life she had left behind, not just rapt conjuring. Besides “Mesi, Papa Vincent,” she repeated, “Desalin pas vle oue blanc,” which means “Dessalines doesn’t like whites.” Late at night when she came into my room, she returned to the beauty and force of her life in Haiti.

Her longing was consecrated most often in this homage to Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who proclaimed Haitian independence in 1804. She praised only the fierce Dessalines — called “barbaric” by most historians — not the urbane Toussaint l’Ouverture or Henri Christophe, who was turned into a god or spirit by the Haitian people. He is still invoked as a lwa in vodou ceremonies in the countryside. Rejecting things French and unconcerned about social graces, he fought to give land to ex-slaves who had only recently been considered property themselves.

In the South, my mother concealed her past, even as she remained estranged from the whites around her. By the time my mother got to Nashville, she recognized the necessity to become as white as possible. A gilded white lady of the South, that’s what my father wanted. Confined by the role she assumed, she performed her new identity. Hiding herself beneath a false smile and pale skin, she wrapped her discomfort and later her sorrow in silks and jewels. This denial of her history was not anything like a power grab for white power and privilege, but rather a casual act performed in exchange for a lifestyle of luxury. This false if stylish veneer killed her spirit and destroyed any chance for happiness.

I can reckon with her life and mine only through how far I fell away from whiteness or how close I could come to black. “Who knows what evil lurks in the heart of men? The shadow knows.” We lived, my mother and I, in a world that flickered back and forth between black and white, darkness and light. Nothing could be secure.

One day she pulled a magnolia off the tree in our front yard. She grabbed it in her hand like a castanet, shook it, and pulled off the white leaves. “There,” she sighed, “There — look — and see the red and the rot.” I was astonished by the violence of that gesture and the softness of her voice. She was entranced by whatever had died and gone bad. She knew that it had once lived in beauty.

¤

A white spider too small for me to truly make out its legs came swinging down lightly. It hovered over the pages about my mother, then two filaments came through the sunlight, now onto the desk, then around my cup of tea, then onto other pages, and now it comes toward me. So fragile and precarious that I’m afraid to move: I feel that it enveloped me in its threads. Wrung out from the innards of her being, they loop me into her life.

My mother’s past comes to me in flashes: fragments of Sinatra’s voice, the sound of laughter or the feel of her slap across my face. Her photos lead me like patches of light into a world that was but is no more. Not long after I brought them into the house, I smashed my nose against the jamb of a doorway, crushed my fingers in a broken garage door, and shattered my ribs in a fall down the stairs. We found each other again when I least expected it; and in sight of her, with her breath on my neck, I know now that whatever mattered to me, the poems I cherished, the writers I taught, and the words I wrote were inspired by her life and raised up again more fiercely after her death.

¤

When she awakened in bed that morning in Mexico City, she looked up at my father in what seems to be sheer wonderment, or is it just languor in the soft light of a room sometime in midsummer at the beginning of their honeymoon. I had never seen any of these photos, all carefully numbered on their backs in pencil, and kept in two wooden boxes. Only now, with her death behind me, am I struck by expressions that I never saw in life, looks that astonish me in their gentle repose.

Doom is never foretold. Not when you’re young, just married to a man who adores you and takes you away to a place of sun, with dust, lizards everywhere in the cracks, birds wandering lost in streets that remind you of Port-au-Prince. She heard the familiar sounds of suffering and holiness in the bodies of beggars and priests. How bad could things be if you had a gold bracelet on your wrist given to you by a doting husband? She especially liked to see the statues of the Virgin that appeared miraculously on the steps of churches or on altars with candles, gold chalices, violets, and white carnations.

In 1939, right after their marriage, my parents arrived in Mexico. My father drove his Buick Roadmaster convertible from Guadalajara to Cuernavaca, stopping in Mexico City, traveling along roads Graham Greene first captured with his “whisky priest” in The Lawless Roads and then a year later in The Power and the Glory, but I doubt they ever read him. My father didn’t like Catholics. I do not know any details of their journey. No one ever told me stories. All that remains of the visit are photographs. They got there seven years after Hart Crane leapt off the Orizaba into the sea; eight years after Sergei Eisenstein began the film that would be cut and mangled in Hollywood; a year after Malcolm Lowry was deported, his life with the alluring Jan Gabrial a shambles.

My parents began their marriage when the New York World’s Fair opened with the debut of nylon stockings, when Billie Holiday first sang and recorded “Strange Fruit,” Judy Garland sang “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” in The Wizard of Oz, and Gone with the Wind premiered at Loew’s Grand Theater in Atlanta. Franco had just conquered Madrid, ending the Spanish Civil War. They arrived in Mexico a year before Trotsky was axed to death, at a time when over 1,000 American tourists a month visited Mexico, and artists too. None of this — no history, culture, or politics — can be gleaned from these photographs.

The suffering of bulls, yes, and the remarkable poses of my mother, but besides a few scenes of peasants, cacti, churches, murals, or horses, there was only a 17-year-old girl, chosen by a man 20 years older, continuously reinvented in split-second exposures, caught in hundreds of ways: lying down in a two-piece bathing suit on rocks, or sitting, long legs crossed doubly graceful in the rise of the stairs underneath her, or sometimes standing in sunlight, her head rocked to the side and eyes like tinder.

The bulls mattered to her life, even if she didn’t know it then or ever. My father went to bullfights. During those afternoons, what did my mother do? As I remember her broken life, I can’t stop thinking about the bulls, isolated from their kind, released into spectacle, performing their agony. Three quarters of a century later, I look at the pictures. Out of boxes and other wooden and steel containers, and buried deep under other albums, come these relics of a honeymoon. They were not part of anything I knew, nor did they make up any kind of beauty my parents might retrieve about a past when they might have known love or passion.

I thought these photos might tell me something about their past that would otherwise be lost forever. My mother’s face, caught in poses that were never off-guard or random, still does not speak to me. Sometimes she has that immaculate quality of being purified of anything living. When she looks out at my father, the hand drawn up on one side, sultry on the hip, I think of Rita Hayworth, her idol. The earliest films of this love goddess were on my mother’s mind when she left for Mexico with my father.

What more can be known about the honeymoon that left my mother cold, my father clueless? I’m sure that my mother never looked at any of these photos. She had no interest in remembering the past. Her indifference to what she had felt then made her the woman that I grew up knowing. I admired and feared her, but most of all I longed to be close to her, enveloped in the waves of her brown and heavy hair. Just a couple of years after marriage, the soft face of a woman beguiled became impenetrable in its exacting beauty. A veneer set in over her luscious skin, hardness seemed to take over eyes that were once inviting, her smile frozen for the camera. But that unyielding stiffness had not yet set her face in stone. She was not afraid to be vulnerable, and her eyes looked at what she thought she loved.

¤

“Blood poured down the streets,” my mother used to repeat after my father died. Cryptic, she never explained who or what she meant. She liked to hear church bells ringing. She prayed the words she learned as a child in Port-au-Prince, where the nuns at Sacré Coeur, her school in Turgeau, took away the girls’ mirrors and then gazed secretly at themselves: “Je vous salue Marie, pleine de grâce, le seigneur est avec vous.” When she worshipped the Virgin late in life, she told me how God once loved a woman pure and without stain. Then she got confused, and remembered how hard it was to remain pure, especially when you hear stories about the djablesse, or “she-devil.” The most feared ghost in Haiti, she is condemned to walk the woods before entering heaven as punishment “for the sin of having died a virgin.” She laughed. “Think about all those nuns taught they’d go to heaven, but they end up wandering around looking for what they never got or scaring the hell out of those who have it.” With a throaty whisper, she added: “They get you coming and going.”

In Mexico her marriage began with prayers to the Virgin of Guadeloupe, our lady of the hills and patroness of the Indians and the poor, so beautiful in a blue mantle, dotted with stars; with the killing of priests, the ice-ax murder of Trotsky, my father’s hero; and a ride on a Ferris wheel that she never forgot. Each parent lost something that mattered that year in Mexico: my father, his revolution; my mother, her virginity.

She kept repeating things. Round and round, always circling back to the gold coins she threw in fountains, the stones that hit dogs, or the sun that was always too hot. Sixty years later, she recalled things I’d never heard her mention before. Not in sentences, but fragments, words thrown like skipping stones on water. “The sun burns the dust at my feet.” “Two more dogs bled, hit again with stones.” “Gold coins, I have a bracelet of coins.” Sun. Dust. Dogs. Coins. Because they never talked about their Mexico adventure, I had no idea what she meant when she called out these things at the end of her life. The photos before me bring it all back, her memories made visible.

“You remember how scared you got on our honeymoon,” my father said to my mother one day when I was a child, “how you ran from the wheel, and it just kept turning, and you never stopped running.” He said nothing more. Only now do I understand that he must have wanted his young bride to go for a ride with him on the wheel that spun in the sky.

In Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano, set on the Day of the Dead in 1938, Consul Geoffrey Firmin rides with his beloved Yvonne on “the huge looping-the-loop machine” high on the hill in the tremendous heat “in the hub of which, like a great cold eye, burned Polaris, and round and round it here they went […] they were in a dark wood.” That feeling of entrapment in time that circled on itself, ominous in its repetition, the return of a past that will not quit, reminds me of my parents’ lives. Perhaps their unhappiness was already fixed in the image of this wheel turning, not just in actuality, but also, and around the same time, in Sergei Eisenstein’s unfinished film ¡Qué Viva México!

All that remained of his visionary epic — mutilated in Hollywood — were three short features that pandered to commercial, and, some argued, fascist interests. Culled from over 200 thousand feet of film rushes, Thunder Over Mexico, Eisenstein in Mexico, and Death Day were released between the autumn of 1933 and early 1934. The last, which Lowry must have seen, features the “Dance of the Heads.” The Ferris wheel revolves dead center, while in the foreground are dancers, and hovering there are three death’s heads, human skulls, whether real or masks it does not matter: not for this story of dashed hopes, where everything seemed purposely to turn life into death, but a death more vibrant than anything life offered, in a land where stone lured more than flesh.

The dead do not die. My mother knew that the earth was squirming with spirits. At any moment she might be caught off guard. While she tangled with things too luscious to be put to rest, mostly the unseen, my father was busy using his photographic techniques to pin down patterns of light and dark, to capture brave matadors at the kill, people on the street, the campesinos in the countryside, women at market, but, most of all, his wife, transforming her into an artifact, as if her body had been raised up from rock and conceived anew in rolls of film.

In one photo he called “Sun Worshipper,” my mother stretches, head thrown back in ecstasy, hair a glossy smooth brown, one leg bent. Her body takes up most of the frame. With the mountains dwarfed behind her, she appears so fluid that she seems to recline sitting up. Years later, it won an award at the High Museum in Atlanta. I remember my father’s long nights down in the darkroom when my mother had already turned her back on him.

At no time did my father refer to their time in Mexico, though he kept and treasured a heavy wool blanket with many-colored stripes, tightly woven, with the shape of what I remember as the indigo blue, orange, and white lineaments of a face like an Aztec god. The other precious remnants of their time together were an elaborate silver water pitcher, sugar bowl, creamer, and large hand-hammered tray. As long as my parents lived, this baroque display that seemed to me heavy as lead remained in the dining room.

¤

LARB Contributor

Colin Dayan is Robert Penn Warren Professor in the Humanities and Professor of Law at Vanderbilt University. Her recent books include The Law Is a White Dog: How Legal Rituals Make and Unmake Persons, The Story of Cruel and Unusual, and, most recently, With Dogs at the Edge of Life. She is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Making Motherhood into Art

Fed and cared for, Menkedick is allowed the space few women have, to sit with her pregnancy and truly grapple with its implications for her life.

Imaginary Children: “The Art of Waiting: On Fertility, Medicine, and Motherhood”

Ellen Wayland-Smith on Belle Boggs's "The Art of Waiting."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2017%2F08%2FHaitian_Revolution.jpg)