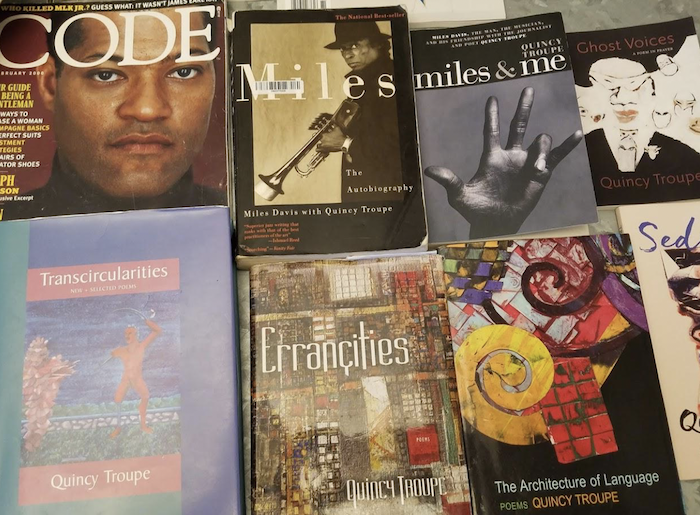

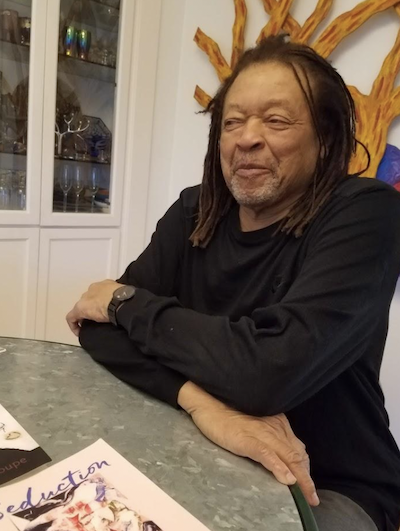

Griot Jali: California’s First Poet Laureate, Quincy Troupe, Returns to His Old Stomping Ground

By Patrick A. HowellJuly 26, 2019

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2019%2F07%2FHowellTroupe.png)

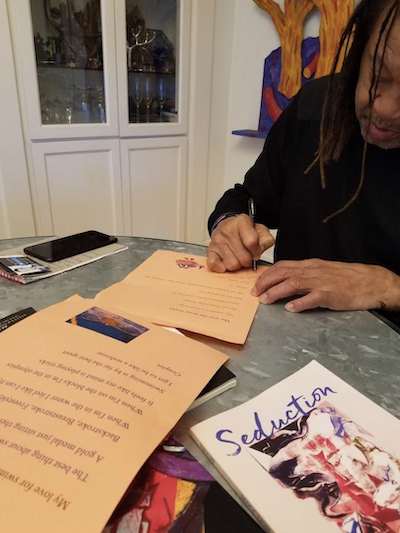

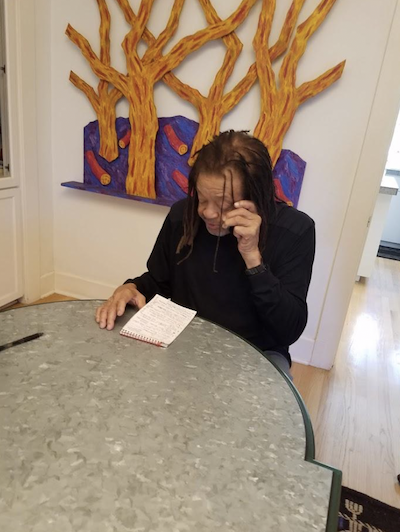

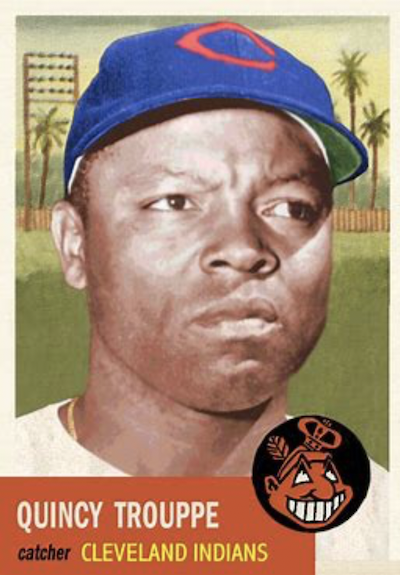

We talk about Harlem, where he now resides, two doors down from the iconic actor Danny Glover (Lethal Weapon Danny, not Childish Gambino Donald) and New York Knicks legend Earl “the Pearl” Monroe, with whom who he wrote a memoir in 2013. We talk about all the fights he had growing up in St. Louis, Missouri, where he was a standout basketball and baseball player (just as his father, Quincy Trouppe, had been). He received an athletic scholarship to Grambling State University but was kicked out for all those fights. “That’s just the way it was,” he confides when I ask why so many. “I didn’t like people getting in my face. I was a different person than I am now.” He would later go on to play basketball in Europe, as his son, Porter Troupe, now does.

We also talk about his mother, a small, beautiful woman, as responsible for his towering accomplishment, and about the gentrification of Harlem, the neighborhood where American culture popped globally into 3-D with the birth of the Harlem Renaissance. We talk about the state of our democracy and the larger culture. This griot jali is a jazz man. He riffs. Improvises. Talks about tough talk with Nobel Prize winner Derek Walcott. Asks about his old friend Ishmael Reed. Recalls Toni Morrison writing Tar Baby in his apartment.

In 2010, Troupe received the American Book Award for Lifetime Literary Achievement. As he took down corners in the culture with Miles: The Autobiography of Miles Davis, the memoir Miles and Me, The Pursuit of Happyness, written with Chris Gardner, and his other books, by his side throughout was an incredible partner, Margaret Troupe, executive director of the Gloster Project and Harlem Arts Salon. Quincy comments, “She’s a great woman. We’ve been together for 40 years now.” Miles and Me is soon to become a major motion picture, with Laurence Fishburne playing him in the film, produced by Rudy Langlais, who previously produced The Hurricane with Denzel Washington.

He has been at work finishing two projects, but I caught up with him on a tour of his past stomping grounds (he is a professor emeritus at UC San Diego), during which he has performed poetry readings in San Diego, Los Angeles, and Riverside, this last at UCR’s famed Writers Week.

[What inspires me is] [e]verything wonderful, provocative, beautiful and creative I encounter each and every day, which could be anything — the natural world, something someone said, some fantastic food I might eat, music, a painting, the style and beauty of a man, or woman, the grace of a human being or animal.

— Quincy T. Troupe, African Voices interview with Angela Kinamore

¤

PATRICK A. HOWELL: Let’s start with a big question: where do you see African-American culture now?

QUINCY TROUPE: The way I look at African-American culture — and American culture also, because all of it is intertwined — I look at it as a continuum. Because I go all the way back to the Harlem Renaissance, and then it starts to come forward, and before that even we had Paul Laurence Dunbar. People try to think in blocks, but I try not to think in blocks. It was important and go back to slavery and then go forward to Paul Laurence Dunbar and then come into the Harlem Renaissance and Langston and Countee. Sterling Brown, more so than Countee Cullen or Langston Hughes — he was a huge influence on me — Sterling Brown who brought those work songs and blues poems, the true blues. If you saw Sterling Brown, you thought he was a white guy. He taught at Howard. He was a big guy. He went to all those great schools like Harvard. He was privileged, but he loved the music and he loved the folklore. He went deep into it — he loved the culture. He was Toni Morrison’s teacher.

Sterling Brown was an important mentor to me because he let me come into his house and he accepted me into his life. He loved my work when nobody else would look at it. He said, “You’re going to do it.” It’s funny because he sounded so country. He was also erudite. He was a great critic, author, teacher. He was brilliant. He was a great poet. He was a great editor. And he was a great teacher. He was my model after I met him. I said, “This guy!”

It’s interesting. You and your contemporaries of the Black Arts Movement are really architects of the culture, the bridge from the Harlem Renaissance to hip-hop. You put down seeds that blossomed into world culture.

Yes. When I moved out here, I was a terrible kid. I was a great basketball player, but I was a terrible kid. I used to like to whip people. That was fun for me, to hit people with bats. I got the scars to prove it. I’ve been shot, stabbed. Growing up in St. Louis was like that. It was violent.

What would instigate these fights?

Just anything! If you step on somebody’s shoes at a party. You could be with a girl that somebody else wanted, you know? I wasn’t in no gang. My family was the most terrifying family in St. Louis. You hit a Troupe? Your [expletive] was [expletive]! ’Cause Troupes would come from everywhere to whoop your [expletive]. I’m serious. [Laughs.]

I just want to tell the truth about my life and how I came to where I am. That’s the way I came up.

My mother had books around the house. My mother was Dorothy Smith Marshall — that was her name. Her maiden name was Smith, but she married my father who was a great baseball player. My father was the third greatest catcher of all time in the old Negro Leagues. Everybody used to come to my house. She was Dorothy Smith Troupe Brown Marshall — ’cause she had married a musician called China Brown. That was all her names. She always had books around the house. She was a great beauty — a beautiful woman — and a great reader. People loved her.

Men loved her. I used to tell her, “Mom, come on! You know what you was doing!” She would leave a handprint on my face. She was five feet two. She read everything. She would make me read books. She made me not only read books, but she also made sure I had a library card to all the libraries in St. Louis — the county library, the city library, the local library — and I had to read all the books. They had a prize for the most read books — it was a book with a worm through it.

The people who used to vie for that was myself, Erlene Richardson, and this guy named Michael who went off the rails and got killed. Also, Walter Lipsey, who went to jail. Walter was brilliant. I was. And Michael was. Erlene was more brilliant that all of us. She was the top student in the school.

What does that mean, books with a worm through it?

The contest was called Book Worms. So, a worm through a little plastic or steel or copper tunnel, and the bigger the worm, the better. There was first place, second place, third place. I used to always get second or third. I could never beat Erlene Richardson. Erlene Richardson read more books than all of us. I used to be mad as hell at her. One time she beat me by one book. She was smart!

What I’m getting to is I played basketball and baseball. My father was also the heavyweight boxing champion for Golden Glove, open division, heavyweight boxing champion who knocked out 55 straight people. So, he did not play. All he had to do was look at us and show us his hand and everybody’s mouth was zipped. He didn’t have to say nothing! He whooped me once, and I never forgot it — with his bare hand. Seemed like I couldn’t walk for two days.

How old were you?

I was like, 13 or 14 … I didn’t stay with him. I stayed with my mother and China downtown. He had told me to stay and watch the house. I went to play baseball and football. I came back, and he was in the house. He was six feet and three inches, weighed 220. He says, “What did I tell you junior?” [Silence.] “You told me to stay in the house.” [Silence.] “And what did you do?” [Laughs.] He administered the whopping of my life. That whopping was too much. I didn’t never not listen to him no more! [Laughs.] And I didn’t live with him. But if he told me to do something, I did it.

I was like that, though. I could go off the rails. And I was hanging with all them boys.

Did he see you at the height of your success?

He saw me when I was getting there.

Was he proud of you?

Yes. He and my mother, I used to take her everywhere. But I was running with some bad guys. I was running with some killers. Fred was my good friend, went to Grambling with me. We both got kicked out of Grambling college … together. For beating up people.

Why? Why did you get in so many fights?

Somebody just says something stupid. It was always the football players. He was a track star, and I was on the basketball and baseball team. I thought the football players were idiots. They would say something smart. I would say you got some head injuries with all that tackling you do with your head. Something had to reduce your brain power. Basketball players? We got a lot of finesse and grace. I used to run with all these people — Fred Holmes — we were all like half-ass gangsters. I got into trouble behind that. I was running with the wrong people. We were watching all those gangster movies, and plus there were a lot of bad dudes in St. Louis. In order to survive, you had to be as terrifying as the next guy or more. I got kicked out of college for beating up a guy … I had a bad temper.

Do you still have any of that temper?

No. I’m cool now. But don’t nobody bother me. I don’t try to bother nobody.

Why do you love Harlem? Why do you live there now, and what are you working on?

I love Harlem. It’s beautiful. The culture is there. You got a lot of great restaurants there. It’s really integrated now. It’s a lot of music. It’s a walking city. There’s a lot to do. So, we’ve been working on this [project with] Rudy Langlais, who was my editor at the Village Voice. I like small presses.

I’m working on the screenplay for Miles and Me. I’m working on my memoir now, which is called The Accordion Years. It is two-thirds finished. And then there is this novel, The Legacy of Charlie Putnam, which I have been writing for 25 years. The novel is basically about his son Langston Putnam. It takes place in St. Louis and Los Angeles.

The memoir is in 11 parts — it starts in 1965 in Los Angeles and it goes back and forth. Hence the name Accordion: it goes back and forward; it goes back and ends in today.

Does it end in harmony?

We’ll see. [Laughs.] I’m happy right now because of my wife and kids.

¤

Patrick A. Howell is an award-winning banker, business leader, entrepreneur, and writer.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

Nikki Giovanni: In Her Revolutionary Dream

Patrick A. Howell interviews poet Nikki Giovanni.

Carmen de Lavallade: A Homecoming

Sasha Anawalt talks to Carmen de Lavallade about her return to Los Angeles.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!