TO RECEIVE THE LARB QUARTERLY JOURNAL, BECOME A MEMBER.

¤

What will people remember about moviegoing, such as it was, in 2020? As COVID-19 vaccinations in the US continue, we are starting to imagine and experience what it will be like to get back to a new normal. I’ve been thinking about going back to the movies for the first time in over a year. It’s still hard for me to envision sitting in the dark with people breathing around me for two hours, though at some point I’ll be ready to share air with strangers for the sake of watching a movie on a big screen again. We go to the movies to be entertained, of course, but as I reflect on my own moviegoing lineage, I’ve also realized some of what we lose when we don’t go to movie theaters. As we emerge from this period of isolation, I’m keenly aware of the ways moviegoing contributes to how we remember our lives, connecting us to people, places, and feelings, as well as to our individual and collective pasts.

When I think of Steven Spielberg’s E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), I remember the excitement and anticipation of standing in line with my mother and hundreds of other people for hours, literally around the block, sweating in the relentless summer heat of the San Fernando Valley in California, waiting to buy tickets. A month after my 13th birthday, I saw The Karate Kid (1984), for the first of what would be at least two theater viewings — with my family most certainly, but also with my elementary school best friend who was headed to private school in the fall, meaning we’d never be as close as when we had been in school together. When The Princess Bride (1987) comes up, I immediately recall seeing it with my best friend, Laurie Palmer, sitting in my first car — a hand-me-down, dirt-brown 1980 Volkswagen Diesel Rabbit — at a drive-in movie theater in Reseda, California. It’s not just the movies; it’s the where, how, when, and with whom.

Some film scholars have argued that moviegoing history might best be told through “close, detailed studies of specific places, people, and chronologies”; others that “in order adequately to address the social and cultural history of cinema, we must find ways to write the histories of its audiences.” [1] For me, this history goes back to my maternal grandparents in Cleveland, Ohio. They were born at the tail end of the Spanish Flu epidemic, when many movie theaters closed their doors to help contain the disease’s spread, and came of age during the Great Depression, when American moviegoing skyrocketed, despite an economic crisis much worse than the COVID-19 pandemic recession.

After my grandmother’s passing in 1998, I ended up with the journals she kept from January 6, 1937, to May 18, 1938, a period of around 16 months that coincided with her senior year of high school. In these, she documented her life on an almost daily basis, commenting on school, work, family, friends, dating, and many, many trips to the movie theater. Her journals provide a glimpse into the role moviegoing played in the life of a working-class teenager growing up in a major Midwestern city during a notable period in American history — not unlike the way my moviegoing rituals reflect my coming of age in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles in the 1970s and 1980s. My grandmother’s journals reveal how “going to the show,” as she often phrased it, factored into her friendships and dating patterns, and occupied so many of her days and nights. After reading them, it is hard to imagine what her life would have been like without movie theaters — as hard as it is for me to imagine my life without them.

¤

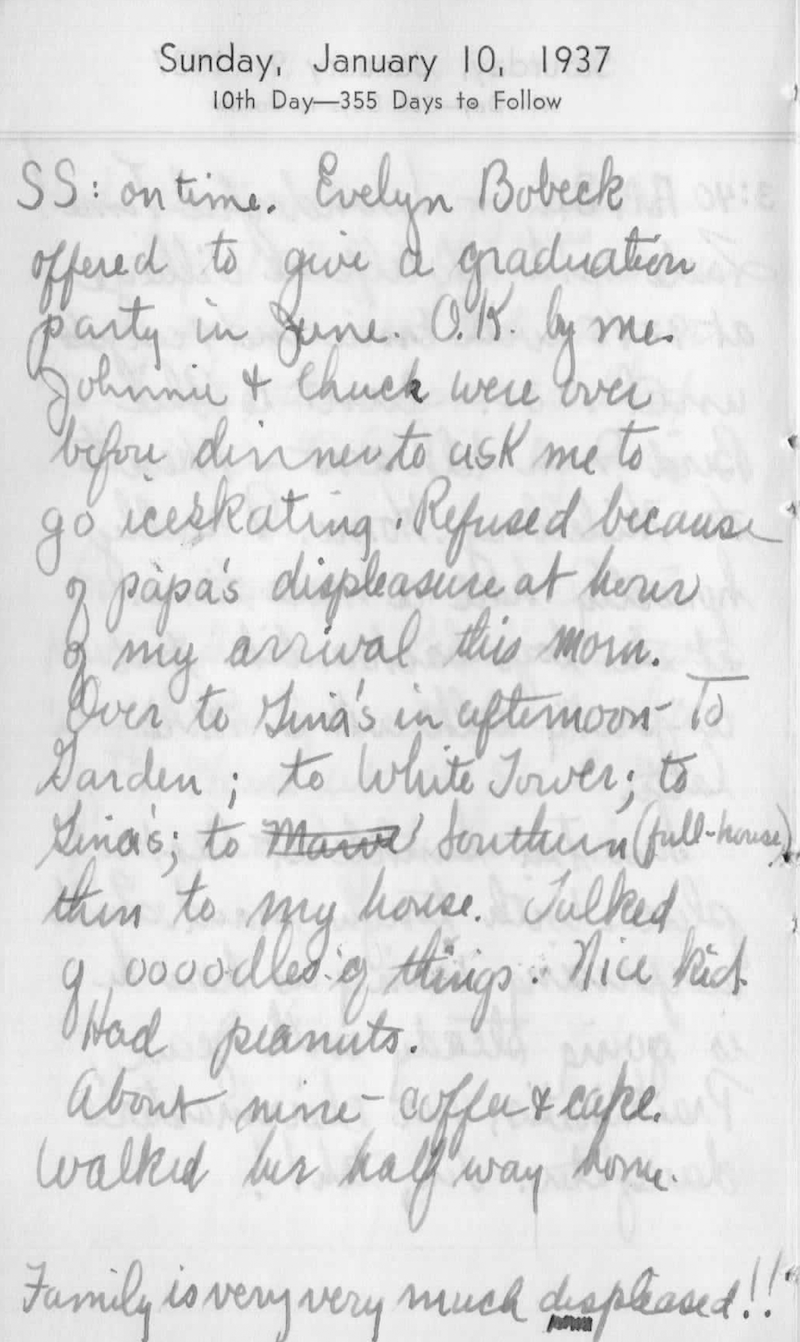

On Sunday, January 10, 1937, 17-year-old Marie Erasmus had a jam-packed day. Before going to bed that evening, she sat down to journal: “Over to Gina’s in afternoon. To Garden; to White Tower; to Gina’s; to Southern (full-house) then to my house.” Her day began with Sunday school in the morning, but most of it was dedicated to leisure: spending time with an acquaintance she described as a “nice kid” who would end up becoming her best friend, and going to the movies not just once, but twice in one day.

The first show was the romantic comedy Love on the Run (1936), starring Joan Crawford and Clark Gable, which Marie and Gina saw at the 1,500-seat Garden Theater. Directed for MGM by W. S. Van Dyke, Love on the Run had completed its run in New York City weeks before, where it came and went in the late fall. A New York Times reviewer deemed it a “slightly daffy cinematic item of absolutely no importance,” but Gable and Crawford had enough star power and chemistry to ensure the film’s box office success despite any formulaic flimsiness. [2] Love on the Run played at seven Cleveland theaters that winter day. Marie and Gina’s decision to see it at the Garden was made out of convenience and habit — it was one of their neighborhood theaters, located less than a third of a mile away from the Erasmus family home. Between picture shows that day, they lunched on a cheap hamburger at the Milwaukee-based White Tower restaurant chain before a stop at Gina’s house, which was conveniently located between the two theaters. These young ladies had plenty of time as they walked from one location to the next, during which they talked about “oooodles of things.”

Their second show of the day, at the Southern, featured 1930s box office phenomenon Shirley Temple in a pre–Civil War Bowery tale, Dimples. Rounding out the bill was The Border Patrolman, a 60-minute low-budget Western programmer produced by Atherton and distributed by Fox, the studio to which Temple was under contract. Marie noted that the Southern was at full capacity that day; apparently, Ohioans were not as put off by Temple’s latest serving of “shameless bathos” as The New York Times film reviewer Frank Nugent was when it played in that city during its initial rollout several months earlier. [3] There is only one other occasion in Marie’s 1938 journals that prompted her to comment on how crowded a movie theater was: when she went to the Lyceum theater with the man whom she would eventually marry — my grandfather, Michael Patrick — and found that it “was packed; so we came home and talked to folks.”

¤

Growing up in Canoga Park, California, I often went to the movies once or twice a week. Before I was a teenager with wheels of my own, my mother was the ringleader of these outings, orchestrating regular acts of illicit movie afternoons. She believed that a single ticket, always matinee, bought its buyer admission to the theater for the day. When showtimes necessitated, we would head to the bathroom after one movie ended, lingering awkwardly by the sinks until she was confident that the ticket takers for showing #2 had moved on and the lights would be down. A stealth, coordinated strike, we would slide into the theater for the second half of a self-appointed double bill, calm enough to avoid suspicion but expeditious enough to evade detection, landing in our stolen seats just like we belonged there without missing a second of the “get one free” movie.

On Sundays, my mother sat at the kitchen table and mapped out these movie days from the listings in the “Calendar” section of the Los Angeles Times, using a pen to circle conveniently spaced showtimes. No doubt there was a thrill to planning these outings, for her at least — less so for her reluctant co-conspirators, which included me and, when she got old enough, my five-years-younger sister. My father never joined us, no doubt disapproving of the endeavor and unwilling to be party to the crime. I was perennially torn between anxiety and, of course, absolute delight in getting to spend a day at the movies.

These were golden moviegoing years, not just for me but for the Hollywood studios that practically minted money with a steady stream of blockbusters. I still experience nostalgia when I recall what it felt like to see films like Star Wars (1977), The Breakfast Club (1985), and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) for the first time, on a big screen in a totally sold-out theater; to be in the midst of an audience laughing, loudly and in synch, during movies like Tootsie (1982) and Back to the Future (1985); the tension-induced hush that accompanied serious fare like Kiss of the Spider Woman (1985) and Witness (1985), which made me feel like I was seeing grown-up movies. (Both were, in fact, rated R.)

And, speaking of grown-up movies: once, my mother insisted that my grandmother, visiting from Ohio, accompany us to see David Lynch’s The Elephant Man (1980). I was an extremely sensitive nine-year-old with no capacity for handling such a deeply disturbing film. When my uncontrollable sobbing began to irritate the other audience members, my grandmother took me into the lobby and let me cry on her shoulder while my mother, who was not about to miss the second half, finished the movie. Whatever portion of the film I actually saw inspired nightmares for months, and to this day, I have yet to watch it in its entirety, despite the fact that I’m a professor of film history who has since studied much more sinister documentary material.

¤

I’m certain that my grandmother never saw the end of The Elephant Man, either, but I know she watched her fair share of movies from start to finish during her high school years. In her diary, Marie recorded opinions about the films she saw, though she usually kept these short and punchy. She judged Winterset (1936) with Burgess Meredith “Excellent!”; Maid of Salem (1937) with Claudette Colbert and The Prince and the Pauper (1937) starring Errol Flynn “Very good!”; Romeo and Juliet (1936) with Leslie Howard and Norma Shearer “Beautiful!”; Heidi (1937) with Shirley Temple and Jean Hersholt “A truly good picture”; The Awful Truth (1937) with Irene Dunne and Cary Grant a “good picture”; Fredric March in The Buccaneer (1938) “the life story of Jean La Fitte, a New Orleans privateer. Excellent”; Hurricane (1937) with Dorothy Lamour “a marvelous picture”; and Clark Gable, Myrna Loy, and Spencer Tracy in Test Pilot (1938) “Excellent.”

She also “Liked song — ‘They Can’t Take That Away From Me’” in the Fred Astaire–Ginger Rogers musical Shall We Dance (1937). She deemed Bette Davis a “wonderful actress” in the Southern plantation melodrama Jezebel (1938) and purchased the tie-in sheet music so that she could play the theme song at home on the piano. But of all the films she mentions in her journal, there was only one that inspired an especially strong emotional reaction that went beyond pithy evaluations. In an unusually cryptic response written after she returned from seeing Marlene Dietrich in Knight Without Armor (1937), she declared: “It left me in a doubtful state.” Marlene Dietrich’s late 1930s films brimmed with sexual energy and moral ambiguity, rattling this Midwestern teen’s equilibrium, though not nearly as much as her granddaughter would be shaken, years later, by David Lynch’s morose universe.

Marie’s journals depict an array of thriving movie theaters in Cleveland during the Depression era. As a May 16, 1938, article in the Cleveland Plain Dealer gracing the same page of a review of Warner Bros.’s 1938 film Robin Hood — which, by the way, Marie enjoyed — explains,

[E]verywhere we’ve been we’ve read about nothing but starvation and woe in Cleveland. We expected to see bread lines all along Euclid Avenue. But when we got here we found the theaters packed, and people spending money in the stores, and other people about to open up a big bank, and filled restaurants and people getting married.

Though job loss and financial worries weave their way through my grandmother’s journal entries, this reporter’s description of a commercially vibrant city is much more consistent with the way my grandmother spent her money and free time in these years. In fact, Marie never mentions any financial impediments to going to the movies, and often went to multiple theaters and movies in a single day on the weekends, as well as out for hamburgers or ice cream sundaes before or after. She did, however, sometimes note that her parents did not let her go to the movies, on one occasion because she had a cold. “Mom refused to allow me” to go, she vented in her diary, adding that “[a]fter [her friend] Gin[a] left I went upstairs and cried.”

In 1916, it was estimated that “[i]n Cleveland one-sixth of the city go [to the movies] at least once a day.” [4] By 1938, when there were 1,231,828 residents of the Greater Cleveland area, making it the sixth most populous city in the nation, attendance was even higher. And by the late 1930s, there were 110 movie theaters in Cleveland with the ability, at full capacity, to seat 122,500 persons. Many of these were richly appointed motion picture palaces, with seating capacities in the 1,500–3,500 range, the likes of which cropped up in cities all over the country in the boom decade of the 1920s. The 1938 Cleveland Directory records that, “Many attractive moving-picture theatres are scattered throughout the city, the largest being Loew’s Stillman, State, Mall, Park, Granada and Allen, where the stars of the screen are shown in the newest productions.” [5] In Cleveland, there were not enough days of the week to see all the movies that were playing.

Though my grandmother had clear favorites, she regularly mentions seven theaters, which she frequented on both weekends and weeknights. As she put it in a journal entry from the summer of 1937, “Florence & I went to the show. Gosh! That’s the only thing to do around here.” Though this complaint was surely an exaggeration — no doubt recorded with a teenage eye roll as that near-curse spilled onto the page — I know how she felt, with malls and movies the only things it seemed like there were “to do” in the entirety of the San Fernando Valley. My grandmother went to one to three “shows” each week in this period — not unlike her granddaughter on the West Coast 50 years later.

¤

When I was going to the movies in Southern California decades later, my theater options were a far cry from the luxurious picture palaces of my grandmother’s youth. On my regular local beat, I had three relatively modest theater options with one to three screens, plus a multi-screen drive-in. The Fox Fallbrook Theater that was closest to home, and that our family frequented most often, was a single-screen theater that was twinned in 1976. It was located adjacent to the J.C. Penney’s auto center in what would later become the area’s second largest mall (one of three located within two miles of each other), with plenty of room for parking on the acres of asphalt that surrounded it. The theater itself was hardly the stuff that dreams were made of. However, because I grew up just a 30-minute sprint — on a good day — down the 101 Freeway from Hollywood, I regularly saw movies when I was a teenager in the late 1980s in what turned out to be a special way. Despite the fact that I was no longer grifting under my mother’s regimen, I spent my teen years shuttling from one free movie to another.

I happened to live in the land of the never-ending free preview screening, watching films that had not yet been released. Almost every time I went to the Topanga Plaza Mall in Canoga Park — which was more often than I’d care to admit since the mall was my social club and stomping grounds, and I’ve always half-jokingly maintained that Valley Girl (1983) should be considered a documentary — I would be handed movie preview passes. Topanga Plaza was a hotbed of pass-pushers, marauding somewhere between Ice Capades and Contempo Casuals. These way-downstream studio employees were on the lookout for people to press into quid pro quo industry service. The tradeoff was nominal: you got to watch a free movie in exchange for staying after the credits rolled to fill out a short survey card. Did you love, like, or hate the movie? Did you like the ending, and, if not, what would have been better? Would you tell your friends to see this movie? A minute of rapidly scribbled penciling on paper, and I was out the door, with my conscience clear. I had, at least, earned my seat.

¤

The movie theater played an essential part in my grandmother’s family and social life, including her romantic experiences. On February 28, 1937, Marie had an unintentional near encounter with a young man she had been avoiding: “Florence, Howie, & I went to the show. Sat right in back of Ernie. Pretended not to notice him.” Whatever Ernie had done to deserve this shunning, it was not yet the end of his prospects. Seven months later, they went to the movies on a date: “Ernie & I went to the show. I don’t like him — emphatically.” Ernie’s luck had run out and by November, Marie had moved on, though with an equally dim outcome: “Date with Rolland. To the show — when we got home — I refused to kiss him; said ‘Goodnite’; and ran into the house. That’s that!” On May 15, 1938, she went to the Garden “to see Tom Sawyer in Technicolor” on what would end up being a more significant date with the man she would eventually marry, Michael Patrick. Just two days later, Michael took Marie back to the movies, this time to the “Hipp” to see Robin Hood, which she described with unusual enthusiasm as, “A splendid picture also in technicolor. A marvelous production!”

The Adventures of Robin Hood was playing exclusively at the approximately 3,500-seat Warner Bros.–owned Hippodrome Theater, with seven different daily start times. This was an expensive prestige picture for Warner Bros., starring two of their brightest stars — Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland — and the investment worked: it became one of the top grossing films of the year. The Hippodrome had been running large, attention-grabbing advertisements that touted the extravagance of Warner Bros.’s latest production. One of these boldly announced that Robin Hood was “a thousand times more thrilling in Technicolor,” encouraging ticket buyers to pay attention to the costly technological enhancement as part of an effort to create the kind of ticket-hungry audiences that the studios would cultivate so well in the age of the blockbuster. [6] Whether Marie’s excited response was to the film, its flashy production values, or her budding romance, we will never know.

¤

When my grandmother was in her late 70s, she volunteered as an usher at Connor Palace theater on Euclid Avenue, which had been recently restored from the bones of a 1920s movie palace that had fallen into disrepair during downtown Cleveland’s decline years. She loved ushering every week. During a summer visit in the 1990s, I accompanied her on the light rail line downtown, arriving at this dazzlingly majestic, ornate, high-ceilinged, red velvet space, the likes of which I had never seen before. I got to witness firsthand how happy it made her, though I presumed at the time that her joy derived from contributing to the revitalization of Cleveland’s downtown. I wish I had known then about all the time she had spent in the movie theaters lining Euclid Avenue in the 1930s, so that I could have asked her about being back in a space that had been so central to her life her 60 years prior. What memories was she reliving each time she walked into that resplendent lobby and showed people to their seats?

My grandmother’s journals tell just a small part of the story of American moviegoing, specific to a region, city, neighborhood, household, and particular young lady — not unlike her granddaughter’s memories from 50 years later, which would take place not far from the seat of the industry itself. Her young adulthood included hundreds of hours spent going to the show, including with the man with whom she would spend the rest of her life. In one of her last diary entries from May 1938, my grandmother wrote, “Michael called for me at work. Swell of him.” After my future grandfather picked her up, they went, not surprisingly, to a movie, after which they “Stopped for sandwiches. Home to talk until l:45. Can you imagine?”

Indeed, thanks to her diary-writing, I can imagine my grandparents in this courtship phase, seeing movies and sharing meals, getting to know each other into the wee hours of the morning at the start of their lives together. I crave this experience of going to the movies again, even if it is mingled with lingering fears of contagion that we will all have to negotiate. Although movie theater attendance had been in steady decline in the years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic, I wonder if it might boomerang back in the post-vaccination era precisely because the isolation of the past year-plus inspires a new appreciation for laughing, crying, screaming, and feeling something together, fulfilling our appetite for communal experiences.

At the very front of her 1937 diary, Marie declares, “This is the truth and should be treated as such!” And here I am, almost 100 years later, with what might be a genetic predisposition for cinephilia, doing just that. I hope that as people return to movie theaters in 2021, that the records of their experiences — more likely made on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram than with pen on paper — will be discoverable for people looking back at this other time of global disruption. It might help them understand all of the things that were lost during the year that we did not go to the movies — and hopefully that will be regained with our return.

¤

Marsha Gordon is a professor of Film Studies at North Carolina State University.

¤

[1] Kathryn Fuller-Seeley and George Potamianos, “Introduction: Researching and Writing the History of Local Moviegoing,” Hollywood in the Neighborhood, ed. Kathryn Fuller-Seeley (Berkeley: University of California, 2008), 3. Richard Malty and Melvyn Stokes, “Introduction,” Going to the Movies: Hollywood and the Social Experience of Cinema, eds. Richard Maltby, Melvyn Stokes, and Robert C. Allen (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2007).

[2] J.T.M., review of Love on the Run, New York Times (November 28, 1936).

[3] Frank S. Nugent, review of “Dimples,” New York Times (October 10, 1936).

[4] Edward M. McConoughey, Motion Pictures in Religious and Educational Work with Practical Suggestions for Their Use (New York: Federal Council of the Churches of Christ in America, 1916), 4.

[5] 1938 Cleveland Directory, available as a PDF from the Cleveland Public Library at cplorg.cdmhost.com.

[6] Cleveland Plain Dealer May 14, 1938. According to Catherin Jurca, the “Hippodrome received the top new releases and ran them for at least a week.” Hollywood 1938 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2012), 38.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

Announcing LARB's Semipublic Intellectual Sessions

A virtual festival of ideas for thinkers, readers, learners of all stripes celebrating 10 years of sharp, engaging, and wide-ranging conversations at...

“Lights, Camera-maids, Action!”: Women Behind the Lens in Early Cinema

Gordon and Grimm consider how the camerawoman fought for relevance and visibility in the days of early cinema and ask why we continue to forget her.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2021%2F11%2FSemipublic-Intellectual-Cover-scaled-1.jpeg)