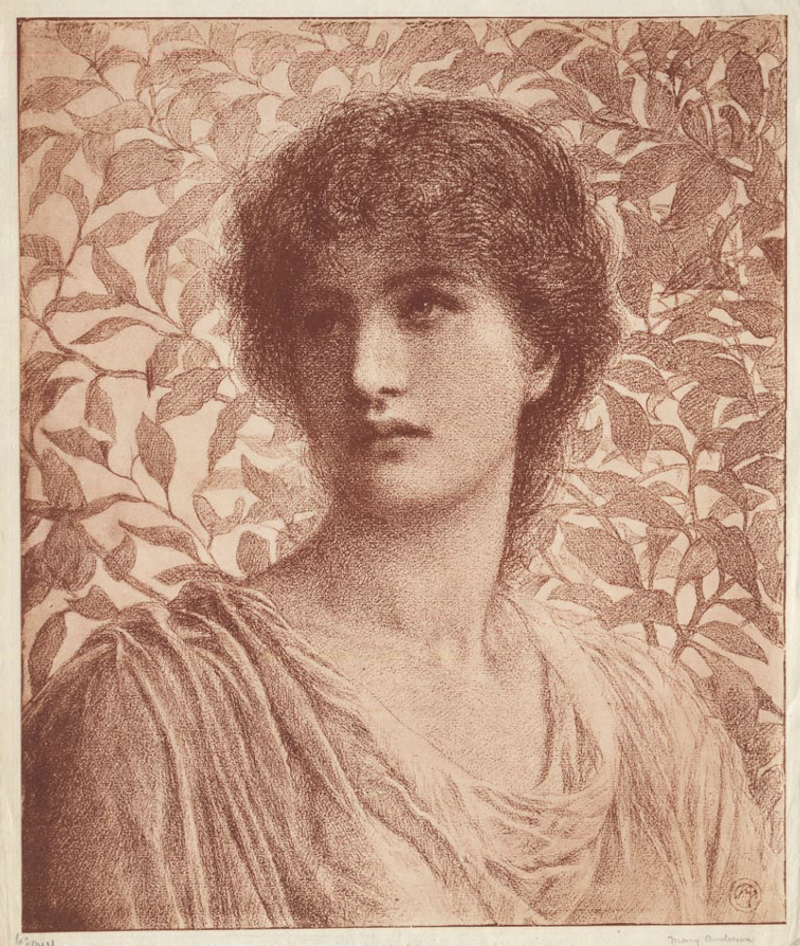

As I browsed the website, one print caught my eye. It was a portrait in red ink of a young woman in a Roman gown, her hair pulled back and her eyes gazing into the distance. The space behind her was filled with leafy vines, though it might just as easily have been William Morris wallpaper. It was surely British, done in what we now call a Pre-Raphaelite or Aesthetic style. Think Dante Gabriel Rossetti or Edward Burne-Jones: idealized images of femininity that were famous and infamous in the second half of the 19th century.

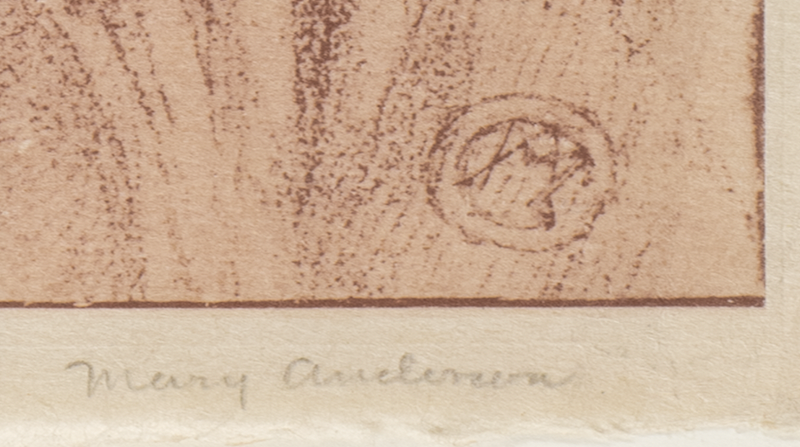

Similar drawings by Rossetti or Burne-Jones regularly sell for five or six figures. But this was a lithograph, not a drawing; and the artist was unknown. The name “Mary Anderson” appeared in pencil in the lower right-hand corner. An artist’s monogram just above, combining an M and A, seemed to confirm the name. But no artist by that name worked in such a style, and so the print seller added a question mark beside the name. And a price in three figures.

Reader, I purchased it.

My day job is teaching 19th-century British and American literature, and the name Mary Anderson rang a bell. At the likely time of the print’s creation — during the 1880s — Mary Anderson was one of the most famous actresses of the day. Born in Sacramento in 1859 and raised in Kentucky, she drew sell-out crowds in New York and London. Oscar Wilde wanted her to star in one of his plays, and she may have inspired the character of actress Miriam Rooth in Henry James’s 1890 novel The Tragic Muse. A quick check confirmed that the image resembled Anderson, albeit in a stylized rendering.

If Mary Anderson was the subject, then who was the artist? I sent the image around to friends and acquaintances who study art history. One suggested Alice Mary Chambers, a little-known British artist with a few vague connections to Rossetti and James McNeill Whistler (of Mother fame). Sure enough, an old auction catalog confirmed that Chambers used the same monogram: not MA, but AMC (the C unobtrusively curves around the other letters).

I wasn’t completely surprised that the artist was a woman. Important research by art historians Jan Marsh and Pamela Gerrish Nunn, among others, has restored to scholarly (and sometimes public) view the lives and works of a considerable number of 19th-century female artists. In 2019, the National Portrait Gallery in London presented “Pre-Raphaelite Sisters,” an exhibition focused on some of these women. Marie Spartali Stillman and Evelyn De Morgan may not be household names, but they are now recognized and collected artists of the Victorian era.

But who was Alice Mary Chambers? Was she part of a larger artistic group? And if she was capable of such skillful and beautiful work, why wasn’t she better known?

When time permitted, I searched British census records, 1880s exhibition catalogs, and library collections for evidence of her life and career. There were brief mentions of her in studies of Whistler, and I discovered that a handful of her letters survived in London and Manchester archives. She had even donated Rossetti’s death mask to the National Portrait Gallery in London. The research wasn’t easy, but eventually the broad outline of her life emerged.

Alice Mary Chambers was born in 1854 or 1855 (no birth certificate seems to survive) in Harlow, some 20 miles northeast of London. Her father, John Charles Chambers, was a prominent Anglican minister who, rather scandalously, incorporated some of the ceremony and ritual of the Catholic Church into his own services. Both of Alice’s parents died when she was young, but she must have found a way to study art, for she described herself in the 1881 census as “Artist in Drawing & Painting.” She was soon exhibiting works in London, Liverpool, and Birmingham.

She was also making friends in the art world: not just Whistler, but also one of the great scoundrels of the era, Charles Augustus Howell. Howell is most famous today for helping Dante Gabriel Rossetti dig up a notebook of poems Rossetti had buried in his wife’s coffin; he was also the inspiration for the blackmailer Milverton in one of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories. Howell was known as an art forger, and Chambers may well have assisted him. In later years, she seems to have given up art and spent considerable time traveling on the continent. She died on May 4, 1920. A brief notice of her passing in the London Times makes no mention of her artistic career.

It’s always possible that a closet, attic, or uncataloged archive somewhere in England is filled with a trove of documents that will fill out this skeleton of a life. But, in all likelihood, we’ll never know as much about Alice Mary Chambers as we do about Rossetti or Whistler, because no one saved her letters and drawings the way so many did for her more famous contemporaries. Furthermore, her artistic career was rather short. It was (and still is) difficult for women to be taken seriously as artists, and this would have limited the commissions available to her.

A handful of Chambers’s works have come up for auction in recent years, mostly watercolors or drawings in red chalk. But many of her works are known only by their titles in exhibition catalogs from the Royal Academy and elsewhere. The great majority are portraits of women: in some cases, these are portraits of contemporaries, often in classical dress (like my lithograph); in others, they are figures from the classical world (“Cydippe,” “A Priestess of Ceres”). Displayed together, I imagine they would provide a striking portrait of late-Victorian concepts of femininity.

I pulled together everything I learned about Chambers and published it in a scholarly article in 2018. I had written about little-known figures, mostly literary, before. But this felt special: it was the first time that an object I owned had inspired me to research and write about its maker. It also added another woman to the boys’ club of late-19th-century London art. Chambers wasn’t some Whistler hanger-on; she was a talented artist whose body of work deserved attention.

When you write about a forgotten artist or writer, you hope that someone will notice. But it isn’t like finding a new poem by Percy Shelley or a new letter by Jane Austen. It may take months, or years, or even decades before another scholar picks up the thread. Young scholars publish their first article expecting that everyone will soon be talking about their clever discovery. But you soon learn to just get on with the next project.

I was getting on with that next project when, early in 2019, I received an email from a distinguished London art dealer. She had seen my article, and she had in her possession a beautiful and previously unknown drawing by Alice Mary Chambers. We corresponded about the possible subject of the portrait — I wondered if it might be Edward and Georgiana Burne-Jones’s daughter, Margaret — but, without evidence, such conversations remained conjecture. When she advertised it in a sales catalog as Portrait of a Young Woman, she kindly thanked me for my input. I emailed her a thank you in response (you’d be surprised how often people use your work without citing it), adding, “I’m hoping a museum acquires it, so that I can see it in person one of these days.”

That was nice. But something even nicer happened after that. In late September, the Huntington Library and Art Museum announced that it had acquired Portrait of a Young Woman. As the Huntington’s news release declared,

Though she was well connected among London’s Pre-Raphaelite and Arts and Crafts artists, and regularly exhibited her work at the Royal Academy, Alice Mary Chambers was a Victorian-era artist who only recently is emerging from obscurity thanks to the recent definitive identification of the monogram with which she signed her work and a 2018 scholarly article on her life and career.

Hey, that was me!

I’m absolutely thrilled that the Huntington has acquired this work. It fits well with the library’s important William Morris collection and the Art Gallery’s stunning Burne-Jones stained glass — and, by good fortune, the Huntington has also just been given a beautiful Edward Burne-Jones portrait of his daughter, Margaret. If my hunch is right, the Huntington now holds two early portraits of Margaret Burne-Jones. But, most important, the fact that an institution of the Huntington’s stature has signaled its interest in a talented but little-known female artist like Alice Mary Chambers means that other public institutions will likely follow. I hope it encourages more work on Chambers, and work on 19th-century women artists more generally.

And one day, when travel is safe, and the Huntington galleries are open again, I will gaze at that portrait and feel the satisfaction of knowing that sometimes research makes a difference.

¤

Thomas McLean is an associate professor in English at the University of Otago in New Zealand. He is the author of The Other East and Nineteenth-Century British Literature: Imagining Poland and the Russian Empire (Palgrave, 2012) and co-editor, with Ruth Knezevich, of Jane Porter’s 1803 novel Thaddeus of Warsaw (Edinburgh, 2019). He has written on art, literature, and migration for The Migrationist and The Conversation UK.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Politics of Rediscovery

By always relegating work by women artists to the zone of the neglected or forgotten, we risk only understanding them in this way.

The Wilde Woman and the Sunflower Apostle: Oscar Wilde in the United States

Victoria Dailey looks back at Oscar Wilde’s wild ride through the United States in the early 1880s.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2021%2F02%2FMcLeanChambers.png)