Fascinated by Synchronicities: A Conversation through Tarot with Elissa Washuta

By Daniel BarnumJune 6, 2021

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2021%2F06%2FBarnumWashuta.png)

ELISSA WASHUTA IS a member of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe and a Cascade descendent. She is the author of two books, My Body Is a Book of Rules (2014) and Starvation Mode: A Memoir of Food, Consumption, and Control (2015), and co-editor, with Theresa Warburton, of the anthology Shapes of Native Nonfiction (2019). Her highly anticipated new book, White Magic, is an essay collection that contains a whole world of subjects: ancient folkways and Instagram witchcraft, settler-colonial place-making and homeplaces, dependence and sobriety, bad boyfriends, Stevie Nicks, video games … A full catalog of the book’s topics would be impossible to produce; the exercise misses the point.

At the structural level, the collection is arranged in sections, each of which opens with a three-card Tarot spread. In the spirit of White Magic, we conducted this conversation as a tarot reading. Each card I drew spurred questions and thoughts related to individual essays and the collection as a whole. I have included images of the cards from my deck, in the place where each presented its questions. What follows has been edited for length and clarity.

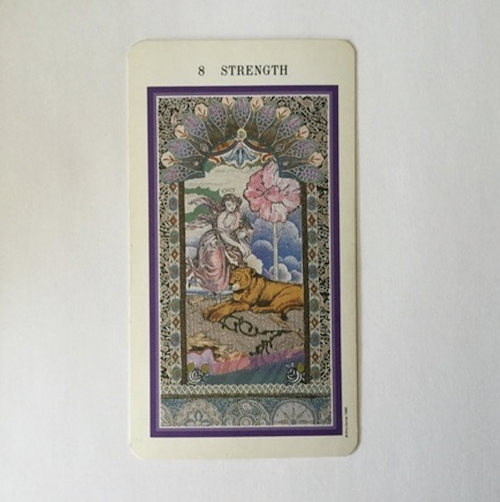

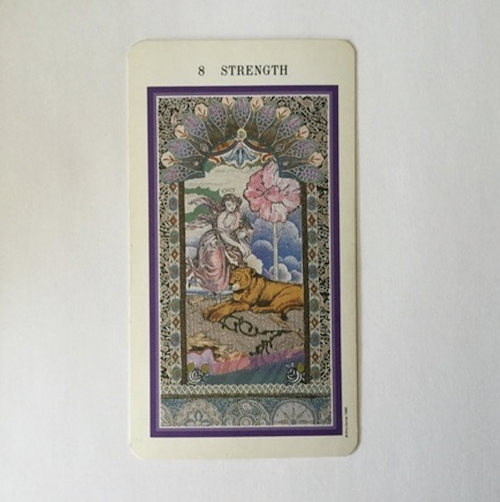

DANIEL BARNUM: Welcome! I structured this discussion by drawing tarot cards on top of your book, and then going from there to sort of meditate on the images. I’m using a deck that features artwork comprising photo, illustration, and textile collages. A lot of the borders especially, but also other elements, are quilted fabric. I drew a total of nine cards, scaling down only to the major arcana. The questions range across topics particular to thinking about the book itself. So, without further ado, the first card I drew for White Magic was Strength.

Thinking about the Strength card made me think about structure and form — which, I know, are interests of yours. To start out, could you discuss your thoughts on, and your approaches toward, form and structure in the book, but also in essay-crafting more generally? I ask this knowing that you’ve edited an anthology, Shapes of Native Nonfiction, with Theresa Warburton, that’s based around form as well.

I have my tarot deck here too and I want to look at the Strength card because I hadn’t been reading recently, but I did a few days ago. I just have the Rider-Waite-Smith. When you brought up the Strength card and form, I started thinking about the way she is holding the lion’s mouth closed. That feels like the process of writing a book like this one: trying to wrangle my sprawling thoughts on everything that’s ever happened to me in my life into this text container.

When I was beginning to conceive of this book, when I really started to understand what it was — around 2017 or the beginning of 2018 — I started to see its scope and understand its concerns and the questions it was asking, and I got nervous about whether I could pull it off. I wanted to do this far-ranging thing that not only represented but also replicated the process of being inside synchronicities and finally turning something over to the universe. That’s really what the book is about, and so I needed to do that in writing the book. I needed to just let stuff happen and not be fully in control of what the outcome was going to be. Usually, I approach form like this: with my hands on the lion’s mouth, calmly in charge of the material, of where it’s going to go. Form-consciousness allows me to create something I can attach my control impulses to while letting the actual questions and answers and investigations develop as they will, so that now I have my hands around it, but it’s a superficial sense of control. That’s my hands, and the material is like the mouth of a lion.

Nice. For me, thinking about that relationship of control — it is a relationship. On my card, the hand isn’t around the lion’s mouth, so there’s a sense of being tamed, but one that requires this enormous investment — time spent “training.”

On your card there are no controlling hands?

Right, she’s got her hand sort of floating above, but there’s no contact.

I feel like that’s where I moved, eventually, in the process of writing this book. Knowing that the lion was there and could do anything at any time, but I was going to take my hands off it and I was just going to let it — you know? I was going to trust that I would find an end to the book; I would find a way that all the pieces fit together and not just let the material drive the form. I get a lot of questions about whether I think about form first or content first. In this book, I finally was not thinking of form and content as being separate at all. I started with nothing, and trusted that it was going to turn into whatever it needed to. That the first sentence would be just a sentence and then the rest of the form was going to take shape in front of me.

That makes sense. I could definitely feel the essays doing the work, and that feeling was really exciting for me as a reader who cares a lot about form. What you’re saying about realizing, maybe for the first time, that form and content were indistinguishable — it feels like that comes through while reading the book. I just felt like something is building and when it happens …

Some of the essays in Act I were among the later ones I wrote. I redeveloped everything that follows. I wrote “Little Lies” and “The Spirit Corridor” in late 2017 and early 2018, and by that point, I had already mostly handed over control to whatever … I think I had already turned away from the ambivalence of trying to figure out whether there was anything greater out there — anything in the unknown, I mean, the answer to whether anything was greater than me was already unequivocally yes — and so I had already pivoted toward trying to track, investigate, and put those pieces together.

So, I didn’t know exactly how it was going to work, but I did know at that point that I was fascinated by synchronicities. I was seeing them in my research and in life. It had been happening for a while, but it really seemed to kick into gear once I got to Ohio in 2017. I can’t remember whether it’s in the book or not, but I think I mentioned the day that Nick White and I went to see the movie Wind River, and then I saw a photograph of my ancestor at a different Wind River, and then Wind River kept popping up, all these different instances of Wind River. Once that started happening, I began to see my role in the stuff I was working on differently. I was paying attention to things that were being shown to me and offered to me rather than trying to make insights. I felt less focused on craft and more focused on being open to the investigation.

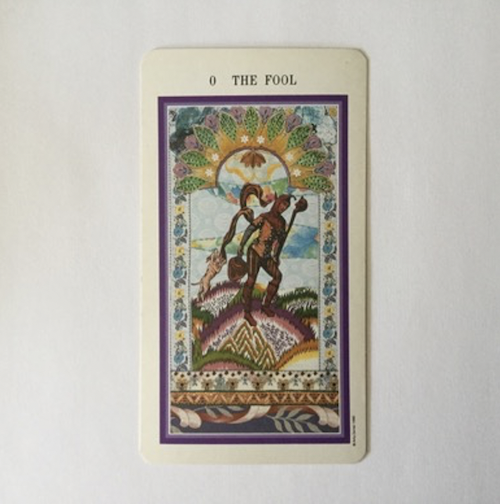

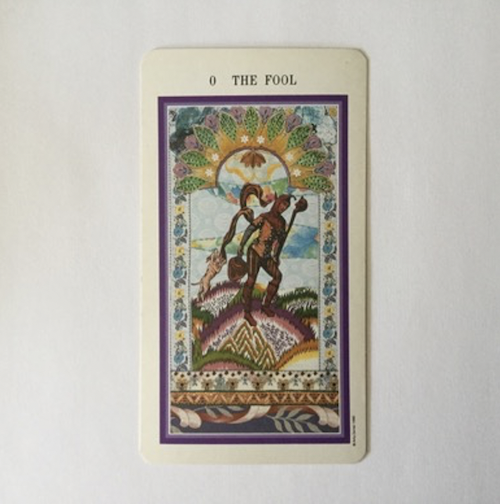

That makes great sense, and also conveniently leads me to the next card and question. What I drew was: The Fool.

Oh, nice; oh, yeah.

I like his little dog. This sort of comes out of what you were just saying — about moving to Ohio in 2017. I thought about the Fool being someone starting out on a journey in an almost happy-go-lucky way. So, this card brought up “how the book began” questions for me, if you want to speak more to that. How did the process develop along the way, especially in terms of connecting essays, where that element of structure enters in? How did you know you were writing a book out of essays that spanned different years?

It’s hard to pinpoint the beginning of the process because I was just trying to find a second book for a long time after finishing My Body Is a Book of Rules — in 2011 or maybe 2012 — but years before it came out, I was looking for an easy project to work on and I did not begin the process of writing this book as the Fool for sure! That came, eventually, but it was the Nine of Swords for a long time.

The earliest thing that I recognized as being part of this book was the Craigslist ad I put up when I saw the woman on the bus — the woman from the future. I wrote about that right after it happened because it was remarkable to see myself from the future. Not a vision or hallucination — she was really there, and then there again and again — so I wrote about that, but I didn’t know what to do with it. I think I was trying too hard to control language. There was also so much other stuff going on that I write about in the book. I was miserable and life was pretty hard, so I worked on various things for a few years. I was in this period of trying to find my real voice. In my first book, I had a thick persona in that narrator. She generally wasn’t meant to be me in the present moment of writing. Some of those essays I did write while things were happening, but I was consciously trying to turn up the volume on that narrator.

But I didn’t want to do that again. I wanted to find a voice that was matured beyond that. For a few years, I was writing essays in a voice that was a little bit too stiff. There was an earlier version of “Rocks, Caves, Lakes, Fens, Bogs, Dens, and Shades of Death” that started as an essay when I was in grad school. I kept almost none of it. But I was attached to that quote from Paradise Lost, so I revisited it and wrote some of an essay, but I didn’t do anything with that for a long time. In 2015, I started working on various essays, but I didn’t see how anything was coming together into a book.

By 2016, I knew I was working toward a book, but I had no idea what it was. In 2017, I started writing “Little Lies,” and at first I thought I was working on an entirely different book. And then all of a sudden it just clicked into place and I could see the way everything was connected. That was the full moment for me. I was going to use all of the material I had been accumulating over the last few years (not all of it — there’s stuff I worked on that is not in this book), but there were a lot of abandoned drafts that I came back to, or completely rewrote in some cases, filled out in other cases — and I think that they had just all been lacking these actual lines of inquiry that I finally had in front of me once I finished writing “Little Lies.”

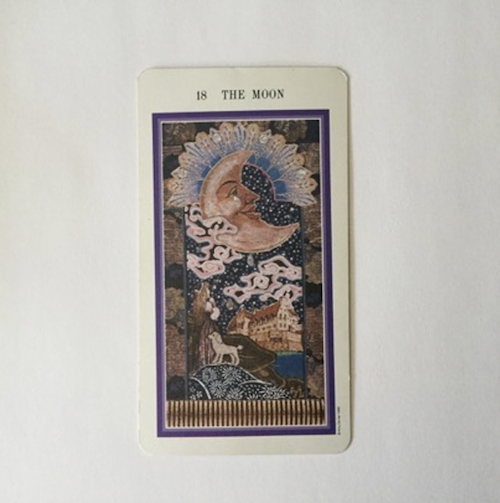

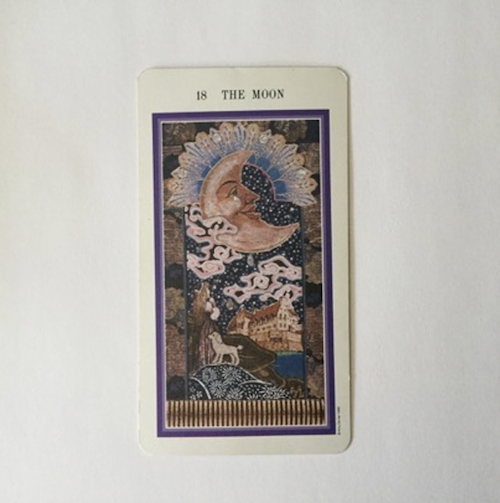

This is somewhat related, but, in terms of the woman from the future … the next card is the Moon.

Oh, it’s so different from the Rider-Waite.

The Rider-Waite has two dogs — a dog and a wolf, right?

I think so, let me find it …

And a lobster?

Yeah, but it’s so sinister.

So, there was no response to the Craigslist ad, right?

There never was. Two people were curious, and one person wrote back that they hoped that I found her. Another person wrote back and I think they were wondering whether they were her, but it was clear that they were not. But none from her, no.

The first instance of seeing myself from the future was seeing a woman in a surgical mask and a wool cape. I saw her. There was something about a reflection that was part of the initial image, because I saw her through a windowpane on the bus. Early in the pandemic, I was going to the grocery store and was wearing this wool cape that I got in Iceland and had on my mask and got out of the car and looked into the bus window as I was locking the car or whatever, and I could see myself very clearly, and I thought, Well, that’s her that’s who I saw, and I got worried that I was going to die or something. But no, I don’t think anything remarkable happened.

Does she feel like a benevolent or non-benevolent presence? And if she appeared before you today, would you say something to her? Would you seek connection with her? What would be the terms of this relationship?

She definitely feels benevolent. I did see her here in Columbus. I saw her at the Old Oak, actually, when I was down there having dinner, when I was looking for neighborhoods because I wanted to buy a house. She had put a notebook on the bar, and I was like, That is a thing I am not supposed to open, but there’s something in there. I think she spoke to me, and I didn’t know what to say because, the thing is — she’s real. It’s not like a movie dream sequence where I’m able to know that this is definitely a specter. Every time, I was like, this is me from the future, and yeah, it might just be this random woman who looks exactly like me — I have that kind of face.

It’s interesting to think about the circumstances in which I’d see her now, and whether I would see her now, because I kind of think that I wouldn’t. I think I’m never going to see her again. I still don’t know what she’s doing here. I still don’t know why she’s been coming, but I do think she appeared at times when I was both hopeful about the future and certain that everything was going to go wrong, and also miserable in some way. I’m out of that now. I don’t think I’m going to see her again.

I do think, if I saw her again, that I would like to talk to her, but I’m still shy. I guess I’d still be anxious about what would happen if she wasn’t me. And what would that mean for everything else that had happened when I saw her in the past? So maybe I just wouldn’t say anything.

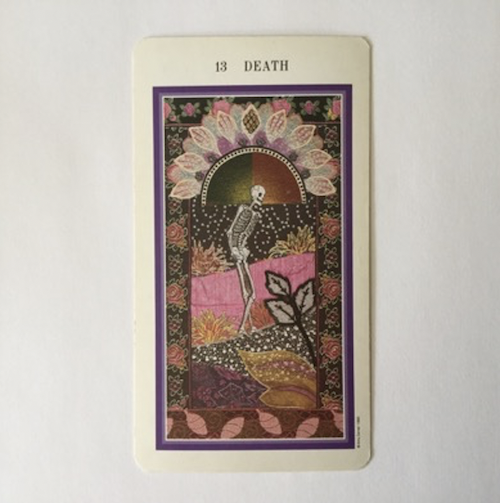

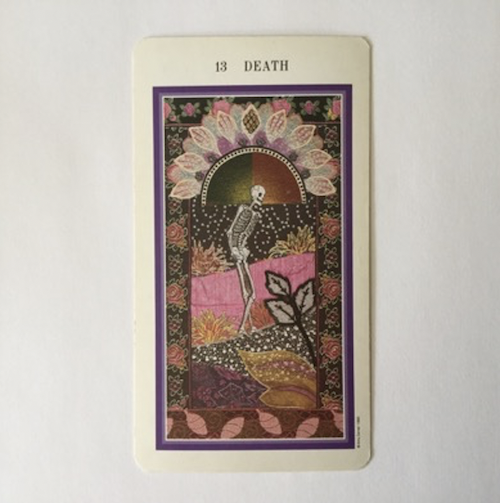

I’m interested in what you were just saying about her appearances during moments that are both hopeful and calamitous, because the next card I have here is Death.

Yes.

Yeah. For my deck, it’s an almost-perfect echo with the Fool. So, this is a question about writing in changed times, writing in restricted circumstances, while also having to retain some sense of livability, of hope. Basically, how has the process — how has writing itself, and reading — been changed and affected by the pandemic?

I haven’t been writing a ton. I spent the first few months working on revisions to White Magic, so I did quite a bit of that. I was intending to not work on anything for a while because I was tired and didn’t want to rush myself into another project. I still felt attached to White Magic and I didn’t feel like the synchronicities had stopped happening, you know? During the revision process, I had my final, final version, and then I played the video game Red Dead Redemption again and had to include another paragraph in the last essay because something else came up that was interesting. I was not ready to be done with these mechanisms that the book is relying on. I think that they have gone away without me realizing, and that’s fine, that’s good. I’m in a good spot where I’m still proud of and interested in the book, but I have been starting to get interested in other projects.

One thing that’s interesting about writing a book that’s this big and seems to be about everything is that there is so much of my life that has been left out of it. A big part is illness. Even in My Body Is a Book of Rules, I hardly touched on some of the major events that are super relevant to that book, like having my gallbladder taken out when I was in college. So, I had been working for years trying to figure out why I felt chronically ill, and had like three naturopaths in Seattle, and nobody could figure it out, and last year, finally, I knew that I needed to push to figure out what was wrong, just because of how often and how readily I get sick. So, I finally got diagnosed with an autoimmune condition, and I think that there has been a lot of stuff percolating for years in research I’ve been doing. I have many, many medical journal articles on my hard drive that are all research for something I’ve known that I wanted to write about regarding illness and health, but for the longest time I didn’t have a question, because I didn’t have the answers I needed to have a foundation. I thought all of this was just in my head.

So, now that I have some answers and can start some real investigations, I realize that this book project has the same feeling of being way too big, because I think my starting place is the impending end of the world. The experience of living between apocalypses, because four-fifths of the Cascade people I’m descended from were killed by an infectious disease in the late 1820s, is something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately. What it means to have a body on that continuum as an Indigenous woman with this chronic health issue of my body hurting itself. I have one essay done and I’ve been starting another. I have ideas for a few more essays about survival and the end of worlds. It’s been hard. I mean, writing during the pandemic. The living conditions have made me sicker, and I’m very tired, and I don’t have time to do everything, but it has also given me permission to put something else at the center of my life that belongs there, which is: Staying alive. Trying to get healthy rather than pushing the writing out.

Speaking of apocalypses and Red Dead Redemption, do you think you will write another video game essay?

Yeah, definitely. I want to write an essay in a few months about The Last of Us and The Last of Us Part II, because The Last of Us Part II takes place in Seattle, and I’ve played it many times now, and developed a somewhat unhealthy relationship with it. I’ve been getting really invested in these apocalypse games — Last of Us, Death Stranding — so I am planning to write something about that.

Cool. I’m thinking about new apocalypse-based projects and living between them and how, in the framing and in historical conception, The Oregon Trail and Red Dead Redemption also become games about the apocalypse.

Yeah, for sure. I was thinking about this the other day with Red Dead Redemption, the second one specifically. I played the first one, but it’s the second one I really responded to. It feels like a game about apocalypse. I think of it as being alongside those other ones, but it’s not about zombies, it’s about the government, and, like, the railroad magnate, and capitalism, and the ending of a way of life for these outlaws. The whole game is concerned with how gunslinging is becoming a thing of the past. Toward the end of the game, once the Native characters come in, it becomes a little silly in that it’s so much like Dances with Wolves — Graham Greene voices the character who’s the analogue to the Dances with Wolves character Kicking Bird, played by Graham Greene. It’s not done in the best way, but I do think it’s effective in showing that the way of life for these outlaws — most of whom are settlers — is disappearing. The idea of an outlaw, regardless of who it is, is a framing of a way of being in relation to the state. So, their way of life is disappearing, but the scale of it becomes more apparent toward the end when they meet the Native characters and the game becomes a lot more concerned with the destructive effects of settlement, not just upon the personal freedom of the settlers but also of the people settlement was inflicted upon. And it is apocalyptic for the Native community in that game.

So, the next card is Temperance.

Oh, nice.

Yeah. There’s a clock face and a very small tree, and we have this angelic Aquarian imagery. Moving away from the implied metaphors of temperance and to the direct image object, the card makes me think a lot about geography and topography in the book — especially about rivers and bodies of water. The book moves from Act I: East Coast (New Jersey, Pennsylvania), to Act II in the Pacific Northwest (Seattle, Coast Salish lands), to Act III in the Midwest (Ohio). This made me think about how rivers form and also traverse the borders we impose, and about how the synchronicity you depict is a kind of fluid motion from disparate but connected sources that arrives into some greater pool of collected meaning. Could you speak to that idea?

When you were talking about this, I was thinking about flooding. Synchronicities are almost like puddles that are left after something floods and then retreats and there are still little pockets of water around on the ground. That’s the mental image that I got. I grew up by a lake and I felt very far from the ocean even though I wasn’t, but when I saw Lake Erie, I cried! I realized how much I missed big bodies of water.

Water has been so much a part of my life that I didn’t even see it as being important. It was just everywhere. Growing up by a lake, my dad being a fish biologist, and then moving to Seattle, where water is just is all around — it’s there even when you’re not in the water. Everything that happens in Seattle is affected by the water, or determined by the water, just because of the way the ship canal creates traffic patterns. Things like that. The shape of the city being between the sound and the lake. I didn’t think about water until I started to think about it in Seattle. I recognized it as being there, but I didn’t fully understand my own relationship with it until I came to Ohio, because so many people in Seattle, when I told them I was moving here, they said, “Oh, I could never be landlocked like that,” and I thought, Why? I don’t understand the concern, it’s not like you’re confined somewhere, it’s not like you can’t ever see the ocean again. But now, I get it. It’s an indescribable thing …

Getting back to temperance and the card, I’m thinking about how the book’s so much about sobriety. I have hardly ever drawn this card for myself. I almost never get this card, which is weird to me, because sobriety is a big thing in the book and in my life the last few years. The ideas of wet and dry feel present in my relationship with geography and also thinking about the way that alcohol use is talked about, and now I know that the autoimmune disease I have is Sjögren’s syndrome, which is a dryness disease. Your body just dries itself out, at least the eyes and the mouth.

Water is one of those things that’s too big to think about and that’s what becomes the subject of a book for me. It’s too big to hold in a conversation, it’s too big to hold in a thought, but if I can have a hundred thousand words, that’s the space where I can hold the things that are too big to think about. Which feels terrible at the beginning of the process — I worry that I won’t pull it off, because it’s too big. But for me, that’s what a book is supposed to be about.

Also, water does a magic thing in that we drink it and it becomes part of us and then it cycles forever. No spoilers, but there’s a dramatic scene in one of your essays where your narrator, after a break-up, drives to the lake and wades in. The first turn is to water …

I had a dream about that the night before last. Not being able to travel has made me realize how much I miss it and how important it is to me. There’s this quality of water — it has the ability to startle in its sensations, even though its qualities are familiar. My brother’s an engineer and he does stuff with water. He gets it; I don’t get it. I don’t want to get it.

The next card I drew was the Devil, reversed. The lovers who appear on the Rider-Waite-Smith deck aren’t here on mine, so it’s just the devil. A mask.

My question is about writing about real people who have hurt you in huge ways and small ways. What is it like to address these people in your writing, and what are the ethical stakes there? What, if anything, do we owe people who act in monstrous ways, people we might have cared about who have “taken off the mask”?

You know, I’m thinking about the mask, and I don’t think that these people who treated me badly ever took off any mask. They never showed me who they really were. They were never vulnerable with me. They had always shown me who they were, and the end of the sentence is the whole book.

There’s a bunch of ex-boyfriends in this book. On one end of the continuum is Henry, who was terrible in a way I could not recognize until I saw I, Tonya, of all things. Seeing the abusive relationship in that movie made something click for me. I said something in the book about how sometimes abusers aren’t charming, and I realized that Henry had never been charming and that he had never misled me about who he was, even though he was kind to me sometimes. So, there’s Henry, and then there are people who were careless with my heart. People who were shitty people, but who were otherwise fine. There’s a “Kevin” character who’s one of my exes — we did have a long history together, and it didn’t work out, but he’s not a monster.

When writing about these characters, I don’t generally think about publication. I just think about what I need to say. I figure, if you are dating a writer, you know what you’re getting into. All of these people — every single person in this book I was in a relationship with — absolutely knew that I was a personal essayist. This is how I clear myself, ethically. Most of them didn’t want to read my work. But it’s out there, and they would have seen that men’s bad behavior is one of the things I write about. They willingly got into relationships with me. So, I try to be accurate. I don’t try to be generous, because I don’t think they all deserve it. And it does feel like, when I’m writing, I’m enacting a process of saying what I couldn’t say to them, which was that they were disrespecting me. Because of whatever social conditioning I’ve had to not say that.

It becomes a whole different thing when the book is coming out. I let myself be very free in the writing, but then it’s exactly what I wanted to say, so I’m not going to revise it to be toothless. At least a couple of them are going to read it, I know they are. I don’t feel great about that, but I think it’s just because I don’t like to upset people. It’s the part of writing and publishing that I hate the most: the real people stuff. Not enough to make me want to write fiction, for sure, but in the months leading up to publication, it has been weighing on me.

So, let’s turn to the next card, which is the Hierophant, reversed.

Oh, that’s always been such a tough card for me. So tough.

Speak to that.

It’s just one of those cards that always, whenever I get it, I have to look it up, and I’m like, No, the definition hasn’t changed; I just don’t understand what it’s trying to tell me. Like I said, I haven’t been doing readings for a while, but I go through phases with this deck where there’s one card I keep getting because there’s a message that I’m refusing to understand from it. The first card that this happened with was Justice, and I think it happened with the Hierophant, and I never understood what it was all about. I just think, Oh, that probably refers to academia …

For me at least, what you’re saying in terms of the card being very present but unknown in many ways helps me to frame my thinking toward a question. In the collection’s longest essay, which takes place in the final act, there is a sense of the synchronicities all clicking into place and lining up in a big way, and it draws from what’s come in the essays before, while pushing into new considerations. It brings in Carl Jung and Twin Peaks, among other things. Thinking about the sense of magic/knowledge the Hierophant holds that is never fully revealed, I want to relate that to an idea Act III of your book introduces: the prestige. Seeing the trick, seeing it happen, but not knowing how. So, this is the prestige question, which is: How did you do it? How did it all form consciously on the page? What sort of planning went into it? Or is there some sort of moment where you’re like, Eureka! I’m the hierophant now?

So, it began in the summer of 2018. After I got home from a visit to Seattle, I started writing down things on note cards. I would write a date and the thing that had happened. I don’t remember when the idea came to do it the way I did, but that was the idea from the outset: events on note cards, one for each date. And partly, it was an ADHD organizational strategy that I need to get all the stuff out from here [points to head] and put it on cards so that I can remember everything that has happened. Everything that has been significant that I have been turning over in my head the last couple of years. At some point, when I felt like it was all out of my head, I looked at my calendar, and then I arranged the cards from January 1 to December 31.

I knew the whole time doing it that this was going to be the biggest act of turning over control, because everything happened on the dates that I said. I don’t feel as if I was trying to jam things into place like I sometimes do in other essays. I was going to let it show whatever it was going to show, because by then I fully believed that something was happening that I didn’t understand. That was this book. And then I created a document where I wrote out little sections for each of them, and I knew how I wanted it to look on the page. After everything was done, I was like, This is very, very long. I liked it; I felt good about it, but I thought, Everybody’s going to hate this. I’m going to get told that this is a failure, and now, most people seem to like it. So, that’s good, because I feel good about it.

I think the way this relates to the Hierophant is like … I’m pushing further into the thing that I’ve always wanted to do, and doing this was an act of doing something on my own terms in the writing, not making any compromises for the marketplace or whatever. This is just the way the essay has to be. And maybe it won’t work for other people, but this is the way I need to write this essay and the way that I need to get toward the end of this book. In some ways, it’s relying heavily on an approach to fragmentation that I have been using for a long time. It’s doing some other things, too, with time.

I’ve always had these ideas about form and fragmentation that I talk about when I teach, and they aren’t the most palatable in the literary publishing marketplace. Fragmentation was not a neutral term when my first book came out. The reason it took so long to write White Magic is that I didn’t want to write another book that was going to be hard to sell or was going to be difficult for a general readership to relate to. Not a general readership, really: an editorial readership. I wanted to be able to sell a book more easily.

But, through teaching, I have come to understand what I know and believe about writing. I don’t think about any of this stuff when I’m sitting down to write. I don’t think too much about form. I don’t check my sentences as I go. I don’t work that way; I don’t think most people do. It certainly makes the work better and more interesting that I have done all of that work outside of the writing process. I think that that’s the result of all the learning and teaching and creating this body of knowledge in Shapes of Native Nonfiction. Part of the intro to that anthology was my job talk for Ohio State. Becoming clear about what I think about form was what allowed me to stretch in that essay, or to stretch within that. To use that as support for my own stretching.

Like: I’ve made it clear in teaching that I have a whole thing about tense. Present tense needs to be used carefully, because its limitations are often more substantial than its positive affordances. Teaching made me aware of that, and made me want to speak to that, and that was a big part of my essay “The Spirit Cabinet.” I knew that it needed to be in present tense, and I was hyper-aware of the fact that that meant I was not going to be making meaning. I was not going to be having insight. Beyond what insight I did have then, or the insight that I, plausibly, could have had then if I forgot. But there was no flexing back from the real present. In looking back at that, it became an interesting constraint — especially as I was revising — to have to work within not being able to reflect or ruminate much, just being in those moments for a hundred pages or so. That was the biggest challenge of the essay: to keep it dynamic while not saying anything that was reflective or analytical.

And that leads neatly to the final card: the Magician, reversed.

I was thinking about how magicians are performers, how they’re converting energy into matter, how the reversal has to do with ideas of — I don’t want to say diminished energy, but restriction and new types of control, performing under difficult circumstances. Like karaoke! And so, my final question is, what would you sing at karaoke?

I would do “Gloria,” by — who’s that even?

Laura Branigan.

Yeah, you know, the last time I went to karaoke, it was the first time I tried it, and I was like, Oh, this is my song from now on. I’m gonna do this again soon. No, so what I would sing is, probably “Alone” by Heart. The biggest surprise of my whole lifetime was going to karaoke with Kristen Arnett, and she sang that song on key, hit every note like it was nothing. I had no idea.

Beautiful. Karaoke is magical.

It really is.

Daniel Barnum lives and writes in central Ohio, where they serve as the managing editor of The Journal. Their poems and essays appear in or are forthcoming from West Branch, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Muzzle, Bat City Review, Pleiades, and elsewhere. Their writing is featured in Best New Poets 2020, and was included as notable in Best American Essays 2020. Names for Animals, their debut chapbook, came out in March 2020 from Seven Kitchens Press. Find them at danielbarnum.net & @daniel_bar_none.

At the structural level, the collection is arranged in sections, each of which opens with a three-card Tarot spread. In the spirit of White Magic, we conducted this conversation as a tarot reading. Each card I drew spurred questions and thoughts related to individual essays and the collection as a whole. I have included images of the cards from my deck, in the place where each presented its questions. What follows has been edited for length and clarity.

¤

DANIEL BARNUM: Welcome! I structured this discussion by drawing tarot cards on top of your book, and then going from there to sort of meditate on the images. I’m using a deck that features artwork comprising photo, illustration, and textile collages. A lot of the borders especially, but also other elements, are quilted fabric. I drew a total of nine cards, scaling down only to the major arcana. The questions range across topics particular to thinking about the book itself. So, without further ado, the first card I drew for White Magic was Strength.

Thinking about the Strength card made me think about structure and form — which, I know, are interests of yours. To start out, could you discuss your thoughts on, and your approaches toward, form and structure in the book, but also in essay-crafting more generally? I ask this knowing that you’ve edited an anthology, Shapes of Native Nonfiction, with Theresa Warburton, that’s based around form as well.

I have my tarot deck here too and I want to look at the Strength card because I hadn’t been reading recently, but I did a few days ago. I just have the Rider-Waite-Smith. When you brought up the Strength card and form, I started thinking about the way she is holding the lion’s mouth closed. That feels like the process of writing a book like this one: trying to wrangle my sprawling thoughts on everything that’s ever happened to me in my life into this text container.

When I was beginning to conceive of this book, when I really started to understand what it was — around 2017 or the beginning of 2018 — I started to see its scope and understand its concerns and the questions it was asking, and I got nervous about whether I could pull it off. I wanted to do this far-ranging thing that not only represented but also replicated the process of being inside synchronicities and finally turning something over to the universe. That’s really what the book is about, and so I needed to do that in writing the book. I needed to just let stuff happen and not be fully in control of what the outcome was going to be. Usually, I approach form like this: with my hands on the lion’s mouth, calmly in charge of the material, of where it’s going to go. Form-consciousness allows me to create something I can attach my control impulses to while letting the actual questions and answers and investigations develop as they will, so that now I have my hands around it, but it’s a superficial sense of control. That’s my hands, and the material is like the mouth of a lion.

Nice. For me, thinking about that relationship of control — it is a relationship. On my card, the hand isn’t around the lion’s mouth, so there’s a sense of being tamed, but one that requires this enormous investment — time spent “training.”

On your card there are no controlling hands?

Right, she’s got her hand sort of floating above, but there’s no contact.

I feel like that’s where I moved, eventually, in the process of writing this book. Knowing that the lion was there and could do anything at any time, but I was going to take my hands off it and I was just going to let it — you know? I was going to trust that I would find an end to the book; I would find a way that all the pieces fit together and not just let the material drive the form. I get a lot of questions about whether I think about form first or content first. In this book, I finally was not thinking of form and content as being separate at all. I started with nothing, and trusted that it was going to turn into whatever it needed to. That the first sentence would be just a sentence and then the rest of the form was going to take shape in front of me.

That makes sense. I could definitely feel the essays doing the work, and that feeling was really exciting for me as a reader who cares a lot about form. What you’re saying about realizing, maybe for the first time, that form and content were indistinguishable — it feels like that comes through while reading the book. I just felt like something is building and when it happens …

Some of the essays in Act I were among the later ones I wrote. I redeveloped everything that follows. I wrote “Little Lies” and “The Spirit Corridor” in late 2017 and early 2018, and by that point, I had already mostly handed over control to whatever … I think I had already turned away from the ambivalence of trying to figure out whether there was anything greater out there — anything in the unknown, I mean, the answer to whether anything was greater than me was already unequivocally yes — and so I had already pivoted toward trying to track, investigate, and put those pieces together.

So, I didn’t know exactly how it was going to work, but I did know at that point that I was fascinated by synchronicities. I was seeing them in my research and in life. It had been happening for a while, but it really seemed to kick into gear once I got to Ohio in 2017. I can’t remember whether it’s in the book or not, but I think I mentioned the day that Nick White and I went to see the movie Wind River, and then I saw a photograph of my ancestor at a different Wind River, and then Wind River kept popping up, all these different instances of Wind River. Once that started happening, I began to see my role in the stuff I was working on differently. I was paying attention to things that were being shown to me and offered to me rather than trying to make insights. I felt less focused on craft and more focused on being open to the investigation.

That makes great sense, and also conveniently leads me to the next card and question. What I drew was: The Fool.

Oh, nice; oh, yeah.

I like his little dog. This sort of comes out of what you were just saying — about moving to Ohio in 2017. I thought about the Fool being someone starting out on a journey in an almost happy-go-lucky way. So, this card brought up “how the book began” questions for me, if you want to speak more to that. How did the process develop along the way, especially in terms of connecting essays, where that element of structure enters in? How did you know you were writing a book out of essays that spanned different years?

It’s hard to pinpoint the beginning of the process because I was just trying to find a second book for a long time after finishing My Body Is a Book of Rules — in 2011 or maybe 2012 — but years before it came out, I was looking for an easy project to work on and I did not begin the process of writing this book as the Fool for sure! That came, eventually, but it was the Nine of Swords for a long time.

The earliest thing that I recognized as being part of this book was the Craigslist ad I put up when I saw the woman on the bus — the woman from the future. I wrote about that right after it happened because it was remarkable to see myself from the future. Not a vision or hallucination — she was really there, and then there again and again — so I wrote about that, but I didn’t know what to do with it. I think I was trying too hard to control language. There was also so much other stuff going on that I write about in the book. I was miserable and life was pretty hard, so I worked on various things for a few years. I was in this period of trying to find my real voice. In my first book, I had a thick persona in that narrator. She generally wasn’t meant to be me in the present moment of writing. Some of those essays I did write while things were happening, but I was consciously trying to turn up the volume on that narrator.

But I didn’t want to do that again. I wanted to find a voice that was matured beyond that. For a few years, I was writing essays in a voice that was a little bit too stiff. There was an earlier version of “Rocks, Caves, Lakes, Fens, Bogs, Dens, and Shades of Death” that started as an essay when I was in grad school. I kept almost none of it. But I was attached to that quote from Paradise Lost, so I revisited it and wrote some of an essay, but I didn’t do anything with that for a long time. In 2015, I started working on various essays, but I didn’t see how anything was coming together into a book.

By 2016, I knew I was working toward a book, but I had no idea what it was. In 2017, I started writing “Little Lies,” and at first I thought I was working on an entirely different book. And then all of a sudden it just clicked into place and I could see the way everything was connected. That was the full moment for me. I was going to use all of the material I had been accumulating over the last few years (not all of it — there’s stuff I worked on that is not in this book), but there were a lot of abandoned drafts that I came back to, or completely rewrote in some cases, filled out in other cases — and I think that they had just all been lacking these actual lines of inquiry that I finally had in front of me once I finished writing “Little Lies.”

This is somewhat related, but, in terms of the woman from the future … the next card is the Moon.

Oh, it’s so different from the Rider-Waite.

The Rider-Waite has two dogs — a dog and a wolf, right?

I think so, let me find it …

And a lobster?

Yeah, but it’s so sinister.

So, there was no response to the Craigslist ad, right?

There never was. Two people were curious, and one person wrote back that they hoped that I found her. Another person wrote back and I think they were wondering whether they were her, but it was clear that they were not. But none from her, no.

The first instance of seeing myself from the future was seeing a woman in a surgical mask and a wool cape. I saw her. There was something about a reflection that was part of the initial image, because I saw her through a windowpane on the bus. Early in the pandemic, I was going to the grocery store and was wearing this wool cape that I got in Iceland and had on my mask and got out of the car and looked into the bus window as I was locking the car or whatever, and I could see myself very clearly, and I thought, Well, that’s her that’s who I saw, and I got worried that I was going to die or something. But no, I don’t think anything remarkable happened.

Does she feel like a benevolent or non-benevolent presence? And if she appeared before you today, would you say something to her? Would you seek connection with her? What would be the terms of this relationship?

She definitely feels benevolent. I did see her here in Columbus. I saw her at the Old Oak, actually, when I was down there having dinner, when I was looking for neighborhoods because I wanted to buy a house. She had put a notebook on the bar, and I was like, That is a thing I am not supposed to open, but there’s something in there. I think she spoke to me, and I didn’t know what to say because, the thing is — she’s real. It’s not like a movie dream sequence where I’m able to know that this is definitely a specter. Every time, I was like, this is me from the future, and yeah, it might just be this random woman who looks exactly like me — I have that kind of face.

It’s interesting to think about the circumstances in which I’d see her now, and whether I would see her now, because I kind of think that I wouldn’t. I think I’m never going to see her again. I still don’t know what she’s doing here. I still don’t know why she’s been coming, but I do think she appeared at times when I was both hopeful about the future and certain that everything was going to go wrong, and also miserable in some way. I’m out of that now. I don’t think I’m going to see her again.

I do think, if I saw her again, that I would like to talk to her, but I’m still shy. I guess I’d still be anxious about what would happen if she wasn’t me. And what would that mean for everything else that had happened when I saw her in the past? So maybe I just wouldn’t say anything.

I’m interested in what you were just saying about her appearances during moments that are both hopeful and calamitous, because the next card I have here is Death.

Yes.

Yeah. For my deck, it’s an almost-perfect echo with the Fool. So, this is a question about writing in changed times, writing in restricted circumstances, while also having to retain some sense of livability, of hope. Basically, how has the process — how has writing itself, and reading — been changed and affected by the pandemic?

I haven’t been writing a ton. I spent the first few months working on revisions to White Magic, so I did quite a bit of that. I was intending to not work on anything for a while because I was tired and didn’t want to rush myself into another project. I still felt attached to White Magic and I didn’t feel like the synchronicities had stopped happening, you know? During the revision process, I had my final, final version, and then I played the video game Red Dead Redemption again and had to include another paragraph in the last essay because something else came up that was interesting. I was not ready to be done with these mechanisms that the book is relying on. I think that they have gone away without me realizing, and that’s fine, that’s good. I’m in a good spot where I’m still proud of and interested in the book, but I have been starting to get interested in other projects.

One thing that’s interesting about writing a book that’s this big and seems to be about everything is that there is so much of my life that has been left out of it. A big part is illness. Even in My Body Is a Book of Rules, I hardly touched on some of the major events that are super relevant to that book, like having my gallbladder taken out when I was in college. So, I had been working for years trying to figure out why I felt chronically ill, and had like three naturopaths in Seattle, and nobody could figure it out, and last year, finally, I knew that I needed to push to figure out what was wrong, just because of how often and how readily I get sick. So, I finally got diagnosed with an autoimmune condition, and I think that there has been a lot of stuff percolating for years in research I’ve been doing. I have many, many medical journal articles on my hard drive that are all research for something I’ve known that I wanted to write about regarding illness and health, but for the longest time I didn’t have a question, because I didn’t have the answers I needed to have a foundation. I thought all of this was just in my head.

So, now that I have some answers and can start some real investigations, I realize that this book project has the same feeling of being way too big, because I think my starting place is the impending end of the world. The experience of living between apocalypses, because four-fifths of the Cascade people I’m descended from were killed by an infectious disease in the late 1820s, is something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately. What it means to have a body on that continuum as an Indigenous woman with this chronic health issue of my body hurting itself. I have one essay done and I’ve been starting another. I have ideas for a few more essays about survival and the end of worlds. It’s been hard. I mean, writing during the pandemic. The living conditions have made me sicker, and I’m very tired, and I don’t have time to do everything, but it has also given me permission to put something else at the center of my life that belongs there, which is: Staying alive. Trying to get healthy rather than pushing the writing out.

Speaking of apocalypses and Red Dead Redemption, do you think you will write another video game essay?

Yeah, definitely. I want to write an essay in a few months about The Last of Us and The Last of Us Part II, because The Last of Us Part II takes place in Seattle, and I’ve played it many times now, and developed a somewhat unhealthy relationship with it. I’ve been getting really invested in these apocalypse games — Last of Us, Death Stranding — so I am planning to write something about that.

Cool. I’m thinking about new apocalypse-based projects and living between them and how, in the framing and in historical conception, The Oregon Trail and Red Dead Redemption also become games about the apocalypse.

Yeah, for sure. I was thinking about this the other day with Red Dead Redemption, the second one specifically. I played the first one, but it’s the second one I really responded to. It feels like a game about apocalypse. I think of it as being alongside those other ones, but it’s not about zombies, it’s about the government, and, like, the railroad magnate, and capitalism, and the ending of a way of life for these outlaws. The whole game is concerned with how gunslinging is becoming a thing of the past. Toward the end of the game, once the Native characters come in, it becomes a little silly in that it’s so much like Dances with Wolves — Graham Greene voices the character who’s the analogue to the Dances with Wolves character Kicking Bird, played by Graham Greene. It’s not done in the best way, but I do think it’s effective in showing that the way of life for these outlaws — most of whom are settlers — is disappearing. The idea of an outlaw, regardless of who it is, is a framing of a way of being in relation to the state. So, their way of life is disappearing, but the scale of it becomes more apparent toward the end when they meet the Native characters and the game becomes a lot more concerned with the destructive effects of settlement, not just upon the personal freedom of the settlers but also of the people settlement was inflicted upon. And it is apocalyptic for the Native community in that game.

So, the next card is Temperance.

Oh, nice.

Yeah. There’s a clock face and a very small tree, and we have this angelic Aquarian imagery. Moving away from the implied metaphors of temperance and to the direct image object, the card makes me think a lot about geography and topography in the book — especially about rivers and bodies of water. The book moves from Act I: East Coast (New Jersey, Pennsylvania), to Act II in the Pacific Northwest (Seattle, Coast Salish lands), to Act III in the Midwest (Ohio). This made me think about how rivers form and also traverse the borders we impose, and about how the synchronicity you depict is a kind of fluid motion from disparate but connected sources that arrives into some greater pool of collected meaning. Could you speak to that idea?

When you were talking about this, I was thinking about flooding. Synchronicities are almost like puddles that are left after something floods and then retreats and there are still little pockets of water around on the ground. That’s the mental image that I got. I grew up by a lake and I felt very far from the ocean even though I wasn’t, but when I saw Lake Erie, I cried! I realized how much I missed big bodies of water.

Water has been so much a part of my life that I didn’t even see it as being important. It was just everywhere. Growing up by a lake, my dad being a fish biologist, and then moving to Seattle, where water is just is all around — it’s there even when you’re not in the water. Everything that happens in Seattle is affected by the water, or determined by the water, just because of the way the ship canal creates traffic patterns. Things like that. The shape of the city being between the sound and the lake. I didn’t think about water until I started to think about it in Seattle. I recognized it as being there, but I didn’t fully understand my own relationship with it until I came to Ohio, because so many people in Seattle, when I told them I was moving here, they said, “Oh, I could never be landlocked like that,” and I thought, Why? I don’t understand the concern, it’s not like you’re confined somewhere, it’s not like you can’t ever see the ocean again. But now, I get it. It’s an indescribable thing …

Getting back to temperance and the card, I’m thinking about how the book’s so much about sobriety. I have hardly ever drawn this card for myself. I almost never get this card, which is weird to me, because sobriety is a big thing in the book and in my life the last few years. The ideas of wet and dry feel present in my relationship with geography and also thinking about the way that alcohol use is talked about, and now I know that the autoimmune disease I have is Sjögren’s syndrome, which is a dryness disease. Your body just dries itself out, at least the eyes and the mouth.

Water is one of those things that’s too big to think about and that’s what becomes the subject of a book for me. It’s too big to hold in a conversation, it’s too big to hold in a thought, but if I can have a hundred thousand words, that’s the space where I can hold the things that are too big to think about. Which feels terrible at the beginning of the process — I worry that I won’t pull it off, because it’s too big. But for me, that’s what a book is supposed to be about.

Also, water does a magic thing in that we drink it and it becomes part of us and then it cycles forever. No spoilers, but there’s a dramatic scene in one of your essays where your narrator, after a break-up, drives to the lake and wades in. The first turn is to water …

I had a dream about that the night before last. Not being able to travel has made me realize how much I miss it and how important it is to me. There’s this quality of water — it has the ability to startle in its sensations, even though its qualities are familiar. My brother’s an engineer and he does stuff with water. He gets it; I don’t get it. I don’t want to get it.

The next card I drew was the Devil, reversed. The lovers who appear on the Rider-Waite-Smith deck aren’t here on mine, so it’s just the devil. A mask.

My question is about writing about real people who have hurt you in huge ways and small ways. What is it like to address these people in your writing, and what are the ethical stakes there? What, if anything, do we owe people who act in monstrous ways, people we might have cared about who have “taken off the mask”?

You know, I’m thinking about the mask, and I don’t think that these people who treated me badly ever took off any mask. They never showed me who they really were. They were never vulnerable with me. They had always shown me who they were, and the end of the sentence is the whole book.

There’s a bunch of ex-boyfriends in this book. On one end of the continuum is Henry, who was terrible in a way I could not recognize until I saw I, Tonya, of all things. Seeing the abusive relationship in that movie made something click for me. I said something in the book about how sometimes abusers aren’t charming, and I realized that Henry had never been charming and that he had never misled me about who he was, even though he was kind to me sometimes. So, there’s Henry, and then there are people who were careless with my heart. People who were shitty people, but who were otherwise fine. There’s a “Kevin” character who’s one of my exes — we did have a long history together, and it didn’t work out, but he’s not a monster.

When writing about these characters, I don’t generally think about publication. I just think about what I need to say. I figure, if you are dating a writer, you know what you’re getting into. All of these people — every single person in this book I was in a relationship with — absolutely knew that I was a personal essayist. This is how I clear myself, ethically. Most of them didn’t want to read my work. But it’s out there, and they would have seen that men’s bad behavior is one of the things I write about. They willingly got into relationships with me. So, I try to be accurate. I don’t try to be generous, because I don’t think they all deserve it. And it does feel like, when I’m writing, I’m enacting a process of saying what I couldn’t say to them, which was that they were disrespecting me. Because of whatever social conditioning I’ve had to not say that.

It becomes a whole different thing when the book is coming out. I let myself be very free in the writing, but then it’s exactly what I wanted to say, so I’m not going to revise it to be toothless. At least a couple of them are going to read it, I know they are. I don’t feel great about that, but I think it’s just because I don’t like to upset people. It’s the part of writing and publishing that I hate the most: the real people stuff. Not enough to make me want to write fiction, for sure, but in the months leading up to publication, it has been weighing on me.

So, let’s turn to the next card, which is the Hierophant, reversed.

Oh, that’s always been such a tough card for me. So tough.

Speak to that.

It’s just one of those cards that always, whenever I get it, I have to look it up, and I’m like, No, the definition hasn’t changed; I just don’t understand what it’s trying to tell me. Like I said, I haven’t been doing readings for a while, but I go through phases with this deck where there’s one card I keep getting because there’s a message that I’m refusing to understand from it. The first card that this happened with was Justice, and I think it happened with the Hierophant, and I never understood what it was all about. I just think, Oh, that probably refers to academia …

For me at least, what you’re saying in terms of the card being very present but unknown in many ways helps me to frame my thinking toward a question. In the collection’s longest essay, which takes place in the final act, there is a sense of the synchronicities all clicking into place and lining up in a big way, and it draws from what’s come in the essays before, while pushing into new considerations. It brings in Carl Jung and Twin Peaks, among other things. Thinking about the sense of magic/knowledge the Hierophant holds that is never fully revealed, I want to relate that to an idea Act III of your book introduces: the prestige. Seeing the trick, seeing it happen, but not knowing how. So, this is the prestige question, which is: How did you do it? How did it all form consciously on the page? What sort of planning went into it? Or is there some sort of moment where you’re like, Eureka! I’m the hierophant now?

So, it began in the summer of 2018. After I got home from a visit to Seattle, I started writing down things on note cards. I would write a date and the thing that had happened. I don’t remember when the idea came to do it the way I did, but that was the idea from the outset: events on note cards, one for each date. And partly, it was an ADHD organizational strategy that I need to get all the stuff out from here [points to head] and put it on cards so that I can remember everything that has happened. Everything that has been significant that I have been turning over in my head the last couple of years. At some point, when I felt like it was all out of my head, I looked at my calendar, and then I arranged the cards from January 1 to December 31.

I knew the whole time doing it that this was going to be the biggest act of turning over control, because everything happened on the dates that I said. I don’t feel as if I was trying to jam things into place like I sometimes do in other essays. I was going to let it show whatever it was going to show, because by then I fully believed that something was happening that I didn’t understand. That was this book. And then I created a document where I wrote out little sections for each of them, and I knew how I wanted it to look on the page. After everything was done, I was like, This is very, very long. I liked it; I felt good about it, but I thought, Everybody’s going to hate this. I’m going to get told that this is a failure, and now, most people seem to like it. So, that’s good, because I feel good about it.

I think the way this relates to the Hierophant is like … I’m pushing further into the thing that I’ve always wanted to do, and doing this was an act of doing something on my own terms in the writing, not making any compromises for the marketplace or whatever. This is just the way the essay has to be. And maybe it won’t work for other people, but this is the way I need to write this essay and the way that I need to get toward the end of this book. In some ways, it’s relying heavily on an approach to fragmentation that I have been using for a long time. It’s doing some other things, too, with time.

I’ve always had these ideas about form and fragmentation that I talk about when I teach, and they aren’t the most palatable in the literary publishing marketplace. Fragmentation was not a neutral term when my first book came out. The reason it took so long to write White Magic is that I didn’t want to write another book that was going to be hard to sell or was going to be difficult for a general readership to relate to. Not a general readership, really: an editorial readership. I wanted to be able to sell a book more easily.

But, through teaching, I have come to understand what I know and believe about writing. I don’t think about any of this stuff when I’m sitting down to write. I don’t think too much about form. I don’t check my sentences as I go. I don’t work that way; I don’t think most people do. It certainly makes the work better and more interesting that I have done all of that work outside of the writing process. I think that that’s the result of all the learning and teaching and creating this body of knowledge in Shapes of Native Nonfiction. Part of the intro to that anthology was my job talk for Ohio State. Becoming clear about what I think about form was what allowed me to stretch in that essay, or to stretch within that. To use that as support for my own stretching.

Like: I’ve made it clear in teaching that I have a whole thing about tense. Present tense needs to be used carefully, because its limitations are often more substantial than its positive affordances. Teaching made me aware of that, and made me want to speak to that, and that was a big part of my essay “The Spirit Cabinet.” I knew that it needed to be in present tense, and I was hyper-aware of the fact that that meant I was not going to be making meaning. I was not going to be having insight. Beyond what insight I did have then, or the insight that I, plausibly, could have had then if I forgot. But there was no flexing back from the real present. In looking back at that, it became an interesting constraint — especially as I was revising — to have to work within not being able to reflect or ruminate much, just being in those moments for a hundred pages or so. That was the biggest challenge of the essay: to keep it dynamic while not saying anything that was reflective or analytical.

And that leads neatly to the final card: the Magician, reversed.

I was thinking about how magicians are performers, how they’re converting energy into matter, how the reversal has to do with ideas of — I don’t want to say diminished energy, but restriction and new types of control, performing under difficult circumstances. Like karaoke! And so, my final question is, what would you sing at karaoke?

I would do “Gloria,” by — who’s that even?

Laura Branigan.

Yeah, you know, the last time I went to karaoke, it was the first time I tried it, and I was like, Oh, this is my song from now on. I’m gonna do this again soon. No, so what I would sing is, probably “Alone” by Heart. The biggest surprise of my whole lifetime was going to karaoke with Kristen Arnett, and she sang that song on key, hit every note like it was nothing. I had no idea.

Beautiful. Karaoke is magical.

It really is.

¤

Daniel Barnum lives and writes in central Ohio, where they serve as the managing editor of The Journal. Their poems and essays appear in or are forthcoming from West Branch, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Muzzle, Bat City Review, Pleiades, and elsewhere. Their writing is featured in Best New Poets 2020, and was included as notable in Best American Essays 2020. Names for Animals, their debut chapbook, came out in March 2020 from Seven Kitchens Press. Find them at danielbarnum.net & @daniel_bar_none.

LARB Contributor

Daniel Barnum lives and writes in central Ohio, where they serve as the managing editor of The Journal. Their poems and essays appear in or are forthcoming from West Branch, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Muzzle, Bat City Review, Pleiades, and elsewhere. Their writing is featured in Best New Poets 2020, and was included as notable in Best American Essays 2020. Names for Animals, their debut chapbook, came out in March 2020 from Seven Kitchens Press. Find them at danielbarnum.net & @daniel_bar_none.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Naming the Silences: A Conversation with Melissa Febos

The author discusses her new book, “Girlhood,” a text that mixes memoir, reportage, and the lyric essay.

The Trouble with Re-Enchantment

Jason Crawford examines a new wave of literature on re-enchantment.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!