Eisenstein Versus Sinclair: H. W. L. Dana and “¡Que Viva México!”

By Angela ShpolbergDecember 7, 2018

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2018%2F12%2FShpolbergEisenstein.png)

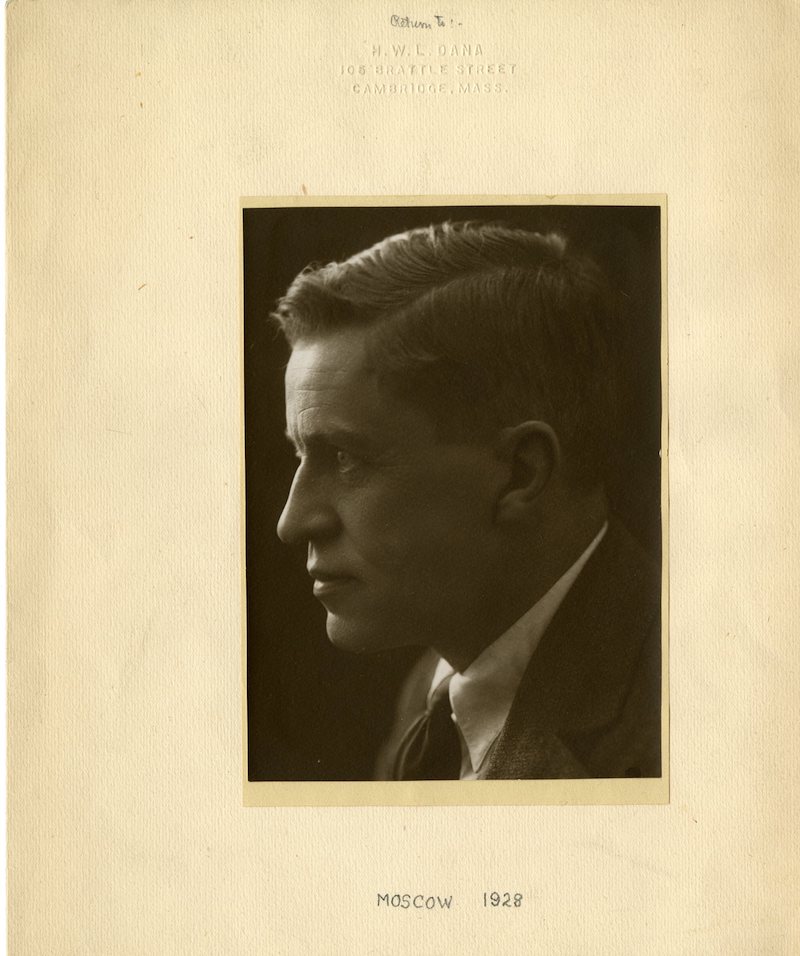

Although the episode has been amply documented in Sergei Eisenstein and Upton Sinclair: The Making and Unmaking of “¡Que Viva Mexico!” and analyzed from multiple angles in numerous articles and books, an important voice has been missing from the discussion up to this point: that of Professor Henry (Harry) Wadsworth Longfellow Dana. [1] Dana, a professor of comparative literature and the grandson of two renowned American writers, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Richard Henry Dana Jr., was a lifelong pacifist and political activist. Among his personal papers in the Harvard University archives are materials that elucidate his role in the Eisenstein episode as well as the national and international forces that tormented Sinclair and tested his — and his comrades’ — ideological and artistic commitments. [2]

Revolution Frees Sergei Eisenstein

Harry Dana’s personal interest in the Soviet experiment and professional interest in Russian theater brought him to Russia in 1927, where he met and befriended Sergei Eisenstein. Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (Bronenosets Potyomkin), released worldwide in 1925, catapulted the filmmaker to celebrity. The film recounted the mutiny aboard the Russian battleship Potemkin, whose mistreated crew took up arms against their officers and the tsarist state in 1905. Even though it was resisted in some Western circles as blatant Soviet propaganda, the film was acclaimed for its experimental editing, unusual camera angles, and its dramatic use of groups of people.

Artists from the West traveled to Moscow to pay homage to the rising star of avant-garde cinema. Eager to discuss his work as well as to learn about developments beyond his country’s borders, Eisenstein willingly entertained his visitors. Among them were Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, Theodore Dreiser and Sinclair Lewis, art historian Alfred H. Barr (who later became the first director of New York City’s Museum of Modern Art), and journalists Louis Fischer, Alfred Richman, and Joseph Freeman. [3] In his “Revolution in the World of Make-Believe” (1930), Harry Dana recalled:

My friends had already seen Eisenstein’s famous film about the Armored Cruiser Potemkin and now wanted to meet the film wizard himself and if possible to see the film called “October” that he has made for the tenth anniversary of the Russian Revolution, the film that is to be shown soon in Boston under the title, “Ten Days That Shook the World.”

“What? More Americans?” was Eisenstein’s characteristic reply, whimsical, but cordial. “They still want to see me. That’s their fault. No matter! Bring them!” [4]

In showcasing the talented, urbane Eisenstein, government bureaucrats hoped to win respect for the Soviet system. Descended from an upper-middle-class Russian family from Riga (now the capital of independent Latvia), Eisenstein was fluent in English, French, and German. His mother, a member of the Russian bourgeoisie, was a woman of independent means. His father, of German Jewish origin, was a civil engineer. Following the family tradition, Eisenstein studied engineering, with a concentration in architecture. Then, as he noted later, “the revolutionary tempest” freed him from the inertia of the course. After devoting his technical expertise to the Red Army for two years, Eisenstein made set designs for the avant-garde theater, directed, and, finally, began experimenting with cinema as a new art form. Eisenstein’s artistic vision and provocative, daring mind entranced his foreign guests. Harry Dana joked that when Eisenstein talked, “his brain as well as his hair seemed to be vibrating with electricity.” [5]

On May 15, 1930, Dana received a telegram from Amkino Corporation, which had been founded in New York City in 1926 to distribute Soviet films in the United States, informing him that Eisenstein had arrived in New York and asking for his help in arranging a speaking engagement at Harvard. On May 21, Eisenstein addressed an audience at Columbia University’s McMillin Academic Theater with a lecture on “The Cinema as Art.” In Boston, George Kraska, secretary of the Artkino Guild — an organization dedicated to screening exceptional experimental films, of which Dana was a board member — took responsibility for organizing Eisenstein’s lecture. And Harry Dana hosted the celebrity at his family’s Longfellow House.

On the day of the Harvard lecture, a luncheon in Eisenstein’s honor was held at Boston’s Hotel Vendome. Dana was pleased that “Eisenstein seemed at home in the setting of Boston society.” The occasion was temporarily marred by a Hollywood stunt, a staged encounter between the filmmaker and the Warner Brothers’ canine sensation Rin Tin Tin. Eisenstein was asked to pose with the dog on a loveseat while the press photographed the “two stars.” In an article headlined “Rin-Tin-Tin Seems Interested,” the Boston Herald recounted that Rin Tin Tin performed some tricks for the guests, but the Soviet visitor seemed unimpressed. Then, the guests “were entertained by Mr. Eisenstein who, in the space of an hour or so, answered approximately 100 questions about Russia, Russian movies, the Russian soul and his own business”:

“You destroy illusions about Russia,” one woman told him.

“Illusions ought always to be destroyed,” he said, “The truth is better.” [6]

Eisenstein delivered his Harvard lecture on Monday, May 26. Postcards had been sent to the department of fine arts’ mailing list and 500 seats remained for those not specifically invited. The next day, The Boston Globe reported:

Mr. Eisenstein, who has been declared the best photoplay director in the world by no less an authority than Douglas Fairbanks, lectured last night at the Baker Library, Harvard Business School […] An audience, which filled every seat and stood in the aisles[,] proved enthusiastic […] The Russian director is a particularly vital, intensely interesting man. He speaks excellent English, although the flow of his ideas proved so strong that at times last night his thoughts ran ahead of the lecture he was giving his audience. [7]

Eisenstein presented ideas that were new to the film industry. He was not interested in traditional narrative. His primary interest lay, rather, in the power of montage to convey abstract notions through the juxtaposition of images. Film was for him a pedagogic tool, one that could foster new ways of thinking.

Mr. Eisenstein Goes to Hollywood

From Boston, Eisenstein continued his journey to Hollywood. “What will Eisenstein do to Hollywood? Or, what will Hollywood do to Eisenstein? […] An irresistible force meeting an immovable body,” wrote journalist Clifford Howard in the August 1930 edition of the avant-garde cinema journal Close Up. [8] His questions would prove prophetic. From one point of view, Eisenstein’s creative energy, entrepreneurial spirit, and innovative ideas should have drawn him close to Hollywood’s elite. He had longed to visit the world’s movie capital, experiment with the latest technologies, and converse with D. W. Griffith. At the same time, however, an unbridgeable gulf separated the Soviet maverick from the American film industry. Clifford Howard offered his analysis.

Cinema history records the names of many foreign directors brought to Hollywood on the strength of personal achievements in their native environment. […] What becomes of them? One of two things — either they “go Hollywood” or they go home. They do not remain if they remain what they were […]

Individualism has no place in Hollywood. American pictures are pattern-made. The patterns are dictated by the box office, and the box office is the composite voice of the Crowd expressed in the clink of silver coin. There is no arguing with the Crowd. It wants what it wants. And mostly it doesn’t want art nor education nor uplift nor cinematic stylism, nor does it care two pennies for any picture because of its director […] And Hollywood has grown rich and great and unshakable because it knows this and accepts it and profits by it.

Yet, of all persons in the world, Hollywood has opened its gates to Eisenstein. The most dynamic individualist in the history of motion pictures. The personification of sublimated cinematic art. The most puissant protagonist of social education by means of the screen. In short, the embodiment of every fundamental taboo of Hollywood. And Eisenstein, on his part, has come to Hollywood, of all places in the world the least in accord with his ideals and purposes and philosophy.

A strange paradox indeed. Eisenstein, the Russian socialist, an impregnable individualist. Hollywood, giant offspring of capitalism and commercialism, the subjugator of the individualist and enforcing a system of collectivism beyond anything yet attained in communistic Russia […] devoting its energies and experience to supplying agreeable entertainment as a commodity to a self-satisfied world in its moments of pastime and mental inactivity.

The outcome of this equivocal alliance will be awaited with more than usual interest. [9]

Eisenstein and Hollywood held substantially different views of the “crowd,” a concept to which Howard had alluded. Deeply interested in the phenomenon of collective behavior, Eisenstein studied it with the precision of a scientist. He preferred the Marxist term the “masses,” distinguished from the chaotic “crowd” or malicious “mob.” The masses held the revolutionary potential to improve society, but to realize this potential, they needed to be enlightened, educated, organized, and uplifted. Cinema’s role was to do just that, to serve as a tool for social edification. In short, whereas Hollywood sought to entertain the crowd, Eisenstein hoped to instruct the masses, who became the primary protagonist in his films. Not altogether surprisingly, then, the first article in English on Eisenstein’s approach to cinema was entitled “Mass Movies” (1927). [10]

The “masses” was a term circulating in early 20th-century popular culture. It was given a particularly leftist cast as the title of the eponymous American journal, which ran from 1911 until 1917 and promoted an explicitly socialist agenda. John Reed, a prolific journalist who wrote for the magazine and had participated in and covered the Russian Revolution, was known to Eisenstein as well as to Dana, who was a graduate student at Harvard when Reed was an undergraduate. Joseph Freeman, a writer and editor of The New Masses, a successor to The Masses that ran from 1926 to 1948, was also acquainted with Dana and had been Eisenstein’s friend since the two met in Moscow in 1926. Eisenstein contributed an essay to Freeman’s book Voices of October: Art and Literature in Soviet Russia, published by the Vanguard Press in 1930.

From the moment Eisenstein arrived in New York, Paramount had been speculating about the future film he was to make for them. The idea of adapting Theodore Dreiser’s novel An American Tragedy seemed to please both the Soviet artist and the studio. Eisenstein set to work and almost completed a screenplay. His vision of the film focused on the social structures in America responsible for the tragedy; Paramount wanted a commercial thriller wrapped around a love story.

In addition to being an intellectual misfit in Hollywood, Eisenstein disregarded its social norms. He “misbehaved,” chatting with butlers at dinners given in his honor and refusing to drink. He was observing the 18th Amendment, he announced, but in fact he did not like alcohol. He found Marlene Dietrich dull and Greta Garbo stupid. His only “refuge” during his California sojourn was Charlie Chaplin.

The relationship between him and the studio had cooled considerably since his arrival. Then, on June 17, 1930, Major Frank Pease, head of the Hollywood Technical Directors Institute and self-styled “professional American patriot,” gave it an arctic blast. Pease wrote to Jesse L. Lasky, one of the founders of Paramount:

If your Jewish clergy and scholars haven’t enough courage to tell you, and you yourself haven’t enough brains to know better or enough loyalty toward this land, which has given you more than you ever had in history, to prevent your importing a cut-throat red dog like Eisenstein, then let me inform you that we are behind every effort to have him deported. We want no more red propaganda in this country.

Pease, a native of New England, had lost his right leg in World War I. His attempts to become a journalist and a Hollywood scriptwriter were unsuccessful. In 1929, he organized the right-wing National Film Committee of American Defenders and, in April 1930, came to prominence when he sent a telegram to President Herbert Hoover demanding that All Quiet on the Western Front, Universal’s adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque’s novel, be banned because it threatened to turn American youth into “a race of […] slackers, and disloyalists.” [11]

Pease produced a 24-page booklet titled Eisenstein, Hollywood’s Messenger from Hell. Widely circulated across the United States, it resonated with disgruntled Americans who sought scapegoats for the woes of the Great Depression. Eisenstein was, in Pease’s words, “a ‘Jewish Bolshevik’ whom the successful Jews of Paramount had imported to make ‘propaganda films.’” The hysteria this campaign sparked brought the so-called Fish Committee to Los Angeles in October 1930. Hamilton Fish was chairman of the House Special Committee to Investigate Communist Activities and Propaganda, and his main concern was the introduction of Soviet propaganda films to the United States.

On October 22, 1930, Eisenstein and Harry Dana met in New York for the premiere of the play Roar China by Russian playwright Sergei Tretyakov, Eisenstein’s friend and Dana’s Moscow acquaintance. Eisenstein held his tongue even though he knew that Paramount planned to publicly cancel his contract the next morning. Paramount claimed that the termination was by mutual agreement. Eisenstein was to return to the West Coast and, from there, depart for the Soviet Union.

Back in Hollywood, Eisenstein told Charlie Chaplin that he still hoped to make an American film. He had in mind a project about Mexico, a country that had intrigued him since his early days in the theater, when he helped stage a performance based on Jack London’s story “The Mexican.” Chaplin suggested that Eisenstein reach out to Upton Sinclair, muckraker, writer, and devoted socialist. Sinclair, sympathetic to Soviet ideals, set about helping the filmmaker. He asked his wife, Mary Craig Kimbrough Sinclair, who came from a wealthy Southern family, to back Eisenstein’s venture financially.

Upton and Mary Sinclair Enter Stage Left

Mary Craig Sinclair (1883–1961), known as Craig at home, grew up in Mississippi. Her father was a well-known lawyer who also owned a former plantation. After receiving an education at the Mississippi State College for Women and the Gardner School for Young Ladies in New York, she had intended to become a writer. [12] In the summer of 1909, while accompanying her ill mother to the famous Kellogg sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan, she met Upton Sinclair, already famous for his novel The Jungle. [13] In 1913, despite her family’s objections, they were married, and Craig embraced her husband’s crusade for social justice. This was Sinclair’s second marriage — the happy one — which lasted for 48 years, until Craig’s death. He openly acknowledged her contribution to his work as his main editor and interlocutor. She managed his papers, dealt with his publishers, and supported him financially.

Backing Sergei Eisenstein after Paramount had cancelled his contract required courage, and Craig had it. On November 24, 1930, she and the Soviet filmmaker signed a new contract. She agreed to put up $25,000 so that Eisenstein could, within three to four months, make a film about Mexico true to his own artistic vision. The picture was to be apolitical, and all negative and positive prints, as well as the story, were to be the property of Mrs. Sinclair; she could market them in any manner and for any price she chose. Eisenstein did not request a salary, but he did ask that his team’s travel expenses be covered, and he reserved the right to show the film in the Soviet Union free of charge. Mrs. Sinclair promised that, after recuperating the original investment, she would pay Eisenstein 10 percent of all proceeds from selling or leasing the film. Mrs. Sinclair’s younger brother, Hunter Kimbrough, was named to manage the project. In December 1930, Eisenstein’s crew, which included his assistant Grigori Alexandrov and cameraman Edward Tisse, arrived in Mexico City.

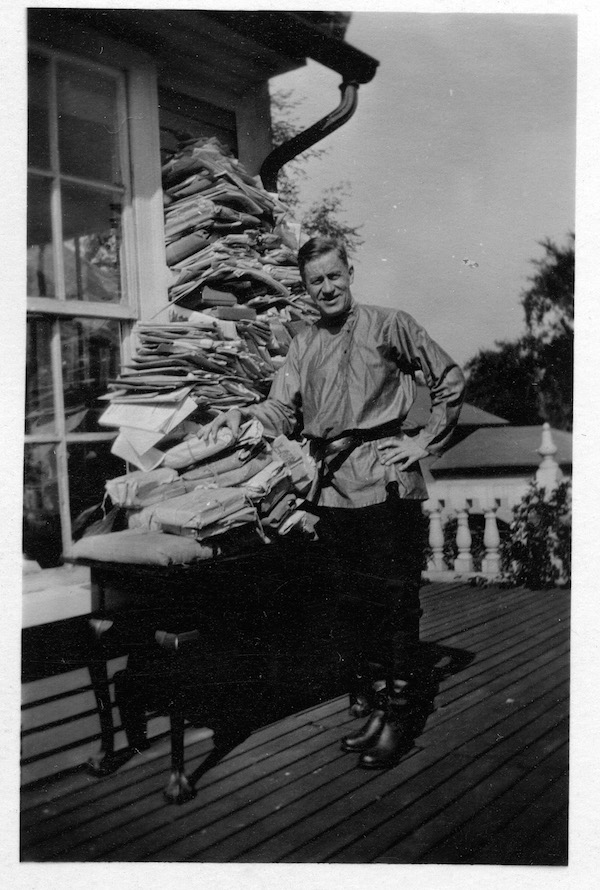

Eisenstein fell in love with Mexico and its people. His team traveled throughout the country and filmed it extensively. However, the production of ¡Que Viva México!, as Eisenstein called the film, encountered a number of unexpected problems. Eisenstein labored over the raw footage tirelessly, but he had never before been constrained by market-driven limits on time and money. In the Soviet Union, the government sponsored the production of films, and authorized filmmakers had access to abundant resources. In addition, Mexico lacked facilities for developing film, so the material had to be sent to Hollywood, thus delaying Eisenstein’s ability to work with it. A perfectionist by nature, Eisenstein produced more and more “takes” from different angles. The shoot took almost three times longer than planned at twice the budget, and still it was not complete.

Upton Sinclair, who was a neophyte in film production, questioned the process but not the project. Still enthusiastic, he set about soliciting additional funds. On November 2, 1931, he wrote to Harry Dana, asking him “to come in for any amount” if the proposition appealed to him. Updating Dana on the film’s progress, Sinclair concluded:

If there is anything else you would like to know, you may write me at once, or you might call upon Mr. Monosson of the Amkino Corporation, New York, which has just agreed to put $25,000 into the picture in its last stage, that is for the cutting and synchronizing.

They have some of the still pictures, and also a copy of the legal documents under which the enterprise is being conducted […] Please answer by airmail if you are at all interested, because if I cannot raise this additional money, I shall have to cut short Eisenstein’s program, and I must know as soon as possible.

There are no previous letters between Sinclair and Dana among Dana’s personal papers at the Harvard archive or the Longfellow House. The surviving exchange has, however, the tone of an ongoing conversation between friends.

It is unclear when Upton Sinclair and Harry Dana first met. They had a number of friends in common, and certainly shared political views. Like Dana, Sinclair was eager to see the Soviet Union — the world’s first workers’ state — succeed. Both Dana and Sinclair had been active in the Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaign, where their paths may have crossed. In 1928, after investigating the case thoroughly and interviewing its key participants and witnesses, Sinclair wrote a documentary novel titled Boston (1928), in which Dana is mentioned several times.

The Mexican film project’s financial problems were worsened by the personal antagonisms that emerged between Eisenstein and Hunter Kimbrough. Both wrote letters to Sinclair full of recriminations, and Mrs. Sinclair, of course, took her brother’s side. On top of it all, Sinclair was increasingly forced to communicate directly with the Soviets, represented in the United States by Amkino and Amtorg, the Soviet purchasing commission.

Even though the contract had already been signed, Amkino abruptly withdrew its $25,000 pledge to the Mexican film because Moscow’s Soyuzkino film studio (later known as Mosfilm), and especially its director Boris Shumyatsky, “considered Eisenstein’s prolonged absence a potentially dangerous precedent.” Sinclair, aware that he could sue Amkino for breach of contract, wrote to its representative, comrade Smirnov:

I wish to say at once that there can be no question of a lawsuit upon my part, because I would never make it possible for the capitalist newspapers to publish an attack upon Soviet Russia emanating from me. But that provides all the more reason why you cannot take advantage of a comrade and commit a breach of faith between friends. […] I have every reason to be convinced of Eisenstein’s complete loyalty to Soviet Russia. But even if he were disloyal, Amkino cannot strike at him through me. I am engaged in raising money to make a picture, and if pledges made to me are broken, my friends lose money which they can ill afford to lose, and my good name is ruined.

Amkino did not respond to the plea. Sinclair found a few more private investors, but the wealthy friends to whom he had appealed, including Dana, largely refused to become involved, offering a variety of excuses.

On November 21, 1931, Sinclair received a telegram directly from Stalin expressing concerns about Eisenstein. Sinclair replied immediately in a letter defending Eisenstein and explaining that work on the film had been prolonged due to the difficult conditions of production. [14] Stalin’s telegram to Sinclair is referred to in nearly all articles and books on the subject of ¡Que Viva México! Few researchers have noted, however, that the telegram did not arrive out of the blue. Without wishing to do so, Sinclair had prompted it. On October 26, he had written to Stalin. In his letter, he boasted that he had been working with the great Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein on an extraordinary project that would become “a revelation of the moving-picture art.” He then went on to make a plea on behalf of a friend of Russian origin, the film technician Fred Danashew. Danashew’s father, Anatole Danashevsky, also a film technician, had left Hollywood for his native Russia to bring his skills to the emerging Soviet film industry.

In his homeland, Danashevsky was tapped to oversee an ambitious project, the construction of the Soyuzkino film studio. The government poured money into its prospective Soviet Hollywood. When the pavilions were completed, however, an engineering mistake became obvious: architects had failed to account for shifting artistic trends and techniques. The isolation of sounds was so bad that it was impossible to make several sound films in parallel. Danashevsky was arrested, accused of sabotage, and sentenced to death by firing squad. Fred Danashew appealed to Sinclair for help, and the author readily obliged. He knew both father and son well, Sinclair wrote Stalin, and they had always been enthusiastic about and loyal to the Soviet Union. He asked that the government investigate the case and that clemency be extended to Danashevsky.

Sinclair was a famous writer, a respected socialist, and a committed friend of the Soviet Union. Ignoring his letter would have been politically unwise. Stalin’s telegram about Eisenstein was, in fact, his answer to Sinclair’s petition on behalf of Danashevky. “LETTER RECEIVED,” it announced at the outset. The evidence did not speak in favor of Danashevsky, Stalin declared, but if Sinclair insisted, he would “SOLICITE [sic] BEFORE THE HIGHPOWERED BODY FOR THE AMNESTY.” In fact, Stalin rescinded the sentence at the last minute. It is likely that Sinclair’s letter saved Danashevsky.

Then, the telegram quickly shifted its focus.

EISENSTEIN LOOSE [sic] HIS COMRADES CONFIDENCE IN SOVIET UNION STOP HE IS THOUGHT TO BE DESERTER WHO BROKE OFF WITH HIS OWN COUNTRY STOP AM AFRAID THE PEOPLE HERE WOULD HAVE NO INTEREST IN HIM SOON STOP AM VERY SORRY BUT ALL ASSERT IT IS THE FACT STOP.

After they received Stalin’s telegram, the Sinclairs agonized over the political consequences of the Mexican project. The following year, Mrs. Sinclair shared the extent of her concerns with Theodore Dreiser:

[H]ere is a fact or two, without any of the mass of details. I ask you to keep it confidential: First, Eisenstein was overdue in Russia. No less a person than Stalin so notified Upton by cable. Do you know what that means? We did not until we were told by certain Russian officials. Upton was becoming a buffer between Eisenstein and his country. Second, the Russians wanted us not to talk about this. Naturally, Russia does not want the outside world to think her artists are deserters. But it was a long and terrible task to get Eisenstein to leave Mexico.

At some point between the middle of January and the beginning of February 1932, after several rounds of conversation with his wife and the other investors, Sinclair ended film production on ¡Que Viva México! All the footage was sent to Hollywood. Eisenstein asked if he could visit Sinclair to explain the situation in person; he still hoped to edit his film. Sinclair, exhausted, had no desire to see Eisenstein. The filmmaker, he thought, should return to the Soviet Union forthwith. Sinclair discussed various possibilities for editing the film with Amkino. Perhaps Alexandrov and Tisse could do so in Hollywood, or Eisenstein might resume his project in Moscow.

At Laredo, Texas, Eisenstein and his crew were denied a reentry visa into the United States. Amkino Corporation and Amtorg intervened. If they crossed the United States without stopping, the filmmakers would be welcome to board a ship bound for home at the port of New York. Despite the agreement, there was more drama at Laredo: customs officers discovered several portfolios of pornographic drawings by Eisenstein in luggage that officially belonged to Upton Sinclair. Eisenstein later confided to a friend that his intent had been malicious, an expression of his pain and fury. “Let Sinclair, the Puritan, explain that one!” Eisenstein chuckled. Sinclair was shocked. The drawings disgusted him, but he also could not understand why the great filmmaker had acted so rashly; after all, his own work could have been confiscated along with the offending illustrations.

Once in the United States, Eisenstein dawdled. It took him 17 days to reach New York, where he showed several parts of the new film material to friends. Sinclair and the trustees of the Mexican enterprise determined that they could no longer trust him. Eisenstein returned to Moscow, but the film reels never followed. Evidence suggests that Sinclair tried his best to resolve the crisis while honoring his commitments and remaining true to his principles. On August 15, 1932, he sent an extremely long telegram to Stalin urging him to have Amkino buy the Mexico footage and ship it to Russia. It read, in part:

EISENSTEIN’S IRRESPONSIBLE ARTIST FRIENDS NOW MAKING NEWSPAPER STATEMENTS HOLDING ME RESPONSIBLE FOR TAKING PICTURE FROM GREAT ARTIST I AM SILENT HOLLYWOOD CONCERNS BESIEGING INVESTORS SEEKING OPPORTUNITY TO INSPECT PICTURE AND PURCHASE IF I WERE COMMERCIAL WOULD SELL THEM PICTURE RETURN INVESTOR’S MONEY AND SAVE MY TIME FOR WRITING BUT AM TRYING TO AVOID CRITICISM ALSO SAVE TRULY FINE RUSSIAN ART WORK EISENSTEIN SHOULD FINISH HIS PICTURE BUT UNDER RUSSIAN GOVERNMENT WHICH CAN CONTROL HIM I CABLED SOYUZKINO SUGGESTING THEY PURCHASE PICTURE […] THIS CABLEGRAM REPRESENTS EFFORT BREAK BUREAUCRATIC RED TAPE OFFICIAL TIMIDITY LACK OF VISION AMOUNT OF MONEY IS SURELY TOO SMALL TO RISK SENSATIONAL PUBLIC BREAK IF PICTURE WERE MINE WOULD MAKE IT PRESENT TO RUSSIA IF I HAD CASH WOULD BUY IT IN NAME OF THIRTY YEARS SERVICES TO WORKERS’ CAUSE I ASK YOU BREAK THIS DEADLOCK IMMEDIATELY HAVE RUSSIA TAKE FILM ON BASIS ENABLING ME KEEP PLEDGES TO FRIENDS COMRADES…

Evidently the telegram was his final attempt to reach any sort of international compromise, for on August 26, 1932, Sinclair wrote to a friend, “apparently the Soviet government is not very much interested in the production […] I have now had to give way, and consent to the picture being marketed in Hollywood.”

Enters Harry Dana, Further Left

Eisenstein’s footage was cut and released as Thunder Over Mexico by American film producer Sol Lesser in 1933. The original crew was acknowledged: Eisenstein was credited as director, Grigori Alexandrov as author of the screenplay, and Edward Tisse as cameraman. The editing of the film reportedly followed Eisenstein’s screenplay notes. A review in The New York Times explained that Eisenstein had shot no fewer than 285,000 feet of film in Mexico, which Lesser had initially reduced to 40,000, from which he produced a “commercial length feature” of a little over 7,000 feet. “It is true,” acknowledged the review, “that the picture is absurdly abrupt in the closing interludes, but for fully three-quarters of its length it shows Eisenstein, the stylist, at his best.” [15]

Eisenstein’s friends and communist activists in the United States aggressively protested Thunder Over Mexico. When the controversy over the film reached its peak in the summer of 1933, Harry Dana found himself in the middle of an extensive exchange between Upton Sinclair and Seymour Stern, co-editor of Experimental Cinema, an international film quarterly published out of Hollywood between 1930 and 1934. Stern, who had befriended Eisenstein in Hollywood, did everything in his power to persuade, even force, Sinclair to send the footage to Eisenstein. He wrote multiple letters and articles, published a 48-page pamphlet that included Eisenstein’s original scenario as well as a summary of “Sinclair’s treachery towards Eisenstein,” and organized protests against Thunder Over Mexico. In addition, he wanted to sue Sinclair, hoping for a judgment that would allow him to purchase at least some of Eisenstein’s footage and generate publicity that would damage the author’s reputation.

On July 20, 1933, Harry Dana wrote to Sinclair, warning him that his reputation was at stake not only in the United States but also throughout the world. Because montage was the essence of Eisenstein’s filmmaking, depriving him of the ability to edit his own film was equivalent to depriving him of his art. For the man who condemned “capital throttling art,” Dana opined, the crisis tested Sinclair’s very integrity. “Which will Upton Sinclair put first,” Dana provocatively inquired: “his money or Eisenstein’s art?”

Dana compared the situation to the then-ongoing controversy between Nelson Rockefeller and Diego Rivera over Rivera’s fresco Man at the Crossroads, commissioned for the Rockefeller Center. Charged with depicting modern social and scientific progress, Rivera centered his allegory on the image of Man as Worker, caught between two conflicting worlds: decaying Capitalism at his right and exultant Communism at his left. Images of Lenin and of a Soviet May Day parade, red flags flying, were prominently featured. Rockefeller asked Rivera to remove Lenin’s likeness. Rivera refused, but he offered to add an American historical leader, perhaps Abraham Lincoln. If he could not retain control over his own artistic product, Rivera declared, he would prefer that it be destroyed. And so it was. Although Rivera was paid in full for the fresco, it was demolished early in 1934. [16]

Dana used the “Battle of the Rockefeller Center” to remind Sinclair that he, himself a great artist, should shield artists’ rights from capitalist incursions. Dana explained why he had declined Sinclair’s invitation to invest in the Mexican project. Even though he supported Eisenstein and his venture wholeheartedly, he felt that investing in art with the expectation of profit inevitably culminated in the exploitation of the artistic creator:

The financial backers speculate on a chance, but the moment things don’t work out well, they are faced with the terrible temptation of bringing pressure so as to get their whole profits as though there had been no element of chance. You have explained this process often. Now you exemplify it.

At the end of the letter, Dana suggested that, at the least, Sinclair send Eisenstein a copy of the original footage so that Eisenstein could cut his own version of the film. Then, “in the name of freedom of art,” audiences would have access to both versions: the one cut by Sol Lesser in Hollywood and the one cut by Eisenstein in Moscow.

Sinclair sent Dana a detailed response on July 26, 1933, in which he heartily defended his “artistic conscience.” Circumstances were beyond his control, he explained:

The Russian Government got their great artist back and avoided having him turn into a White, as Rachmaninov and Shaliapin have done. They owe this solely to our efforts, and we thought they would be ready to do the fair thing about the picture. But Smirnov of Amkino came out here, and I said to him in the midst of a long wrangle: “One thing I want to get clear. Does Moscow want this picture?” The answer was, “Moscow does not want this picture.” You beg me in your letter to arrange for a Russian cutting as well as a Hollywood cutting. Well, that is exactly what I proposed to Smirnov and his answer was delivered with contempt: “Moscow would scorn to enter into competition with Hollywood.”

Of course, he could save his reputation by giving the whole sorry story to the press, Sinclair remarked; the publicity would be stellar advertisement for Thunder Over Mexico. But one consideration held him back: “[M]y interest in Soviet Russia. I am sure that you will appreciate this.”

In a prompt but brief reply on July 30, Dana thanked Sinclair for “taking all the pain” of his lengthy vindication but dismissed it as akin to “the hysteria of the bourgeois feeling fear of the revolutionary worker.” He concluded:

Just as in 1917 you abandoned socialism to support the World War, so it seems as though you now were abandoning the rights of the creative artist to support the rights of the investors. I can only warn you once more that your reputation among lovers of liberty and art throughout the world is being weighed in the balance and found wanting.

The letter was closed with two words: “Very sadly.”

Dana did not let the matter drop. Among his personal papers is a letter dated August 1, 1933, confirming that the Amkino Corporation had received from him copies of his and Sinclair’s letters. “The entire matter concerning Eisenstein and Sinclair is being handled” by Mr. Bogdanov, the message went on, to whom the letters had been transferred and who would soon offer his comments. Amkino thanked Dana for his kind assistance. No further communications to or from Amkino have been found in Dana’s correspondence.

Upton Sinclair wrote another long letter to Dana on August 2, 1933. It would be the final exchange between the two men. Sinclair began by contemplating the last two words written by Dana, “Very sadly”:

My dear Harry:

You say that my letter made you sad — well, yours made me even sadder. It appears that I wrote you that long letter and could not even get across to you the elementary fact that I have no authority at all over what is done in the matter of the picture. I do not suppose there is any use in telling you anything more, and perhaps I am yielding to weakness in answering your various statements.

Eisenstein’s American backers, as Sinclair referred to them, had published a manifesto in The Daily Worker calling for protests at all Los Angeles and New York cinemas where Thunder Over Mexico was to be screened. Sinclair suspected that Seymour Stern was behind the summons to demonstrate. Sinclair also received a warning about a possible stink bomb attack during the Los Angeles screenings, which subsequently required that guards be stationed at all performances. “Am I supposed to be ignorant of what Communist demonstrations are and what they lead to?” asked Sinclair. He and his friends felt they were surrounded if not by bandits, then by lunatics.

While he agreed that artistic license was sacrosanct, Sinclair reminded Dana that the legal rights of investors ensured the proper conduct of business. He wrote that Eisenstein and his crew had engaged in professional misconduct on more than one occasion, and described Eisenstein as a “sexual pervert” based on the drawings found at Laredo, Texas. The letter ended on an emotional note:

How many more things would I have to tell you about your “great” artist before I made you begin to realize that I might have some difficulty in persuading the investors and their trustees and their lawyer to place their property again in his hands, or to rely upon any promises he made? You and your friends, whom you call friends, are doing your best to put me in a position where I have to tell all these stories to defend my own good name.

Finally, I note with a little amusement, not unmixed with “sadness,” that you are one more of these persons who have advised me and my friends to pour out money without limit in behalf of Eisenstein; but when I tell you that I am stranded and suggest that you lend me some money to help pay the storage charges on the negative which Eisenstein will some day have a chance to cut, you do not even mention the subject!

Four Characters in Search of Integrity

Sergei Eisenstein returned to a Soviet Union that had changed a great deal while he was absent, and he found that he could no longer accommodate himself to the “general line.” His attempts to shoot new films were rebuffed, so he took refuge in his teaching at the State School of Cinematography (VGIK) and in writing his theoretical essays, activities neither the government nor his colleagues appreciated. Not until 1938 was he allowed to produce another historical film, Alexander Nevsky. Although the film was a critical success, its veiled condemnation of German Nazism prompted Stalin to pull it from distribution after he entered into a nonaggression pact with Hitler in 1939. Stalin later approved Part I of Eisenstein’s epic film about Ivan IV of Russia, titled Ivan the Terrible, but he halted production on Part II, which remains incomplete.

Harry Dana collected all the newspaper clippings about Eisenstein and his work that he could find in the United States. Some news came to him through a new friend, Jay Leyda, a prominent American film historian who had studied with Eisenstein in the Soviet Union from 1933 until 1936. Leyda shepherded Eisenstein’s theoretical works into publication abroad, to the edification of future generations of filmmakers and film scholars. Although Dana was undoubtedly pleased when Alexander Nevsky was released, he writes, in an unpublished reflection on the film, as someone who has accepted the Soviet authorities’ view of his friend. Gone is the praise of the individual’s artistic vision; instead, Dana celebrates the accomplishments of the “collective,” adhering to standard Soviet rhetoric of lamentable “formalism” and laudable “socialist realism”:

After the lapse of eight years without any finished production for the screen,Sergei Eisenstein has at last freed himself from the aesthetic bonds of some of his earlier formalistic mannerism and he succeeded in giving as much socialist realism as is possible to so old a subject. His imaginative genius for allegory and symbolism is all the more effective when it is working within the bounds of historical subject matter and in cooperation with other directors and with a great composer such as Prokofiev. His individualism has shown itself capable of self-discipline and of collaborating with others in the collectivist art of a complicated modern sound film to which the cooperative habits of a collectivist society lend the best opportunity. [17]

On April 14, 1947, Eisenstein’s American friends and journalists gathered at Boston’s Kenmore Hotel to take part in an open call with the great director. Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible, Part I, was to screen at Boston’s Kenmore Theatre the following day. Serge Koussevitzky, conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Harry Dana, and Jay Leyda talked to Eisenstein. The next morning, The Boston Globe Daily, the Boston Traveler, and The Christian Science Monitor saluted “Russia’s Ace Film Director,” who had spoken live from Moscow to Boston. [18] Less than a year later, on February 9, 1948, Sergei Eisenstein died of a heart attack. He was 50 years old.

In November 1949, Dana received a letter from Marie Seton, a British theater and film critic. It read, in part: “We have not met for years — not, I think, since 1935 […] Now I have something very important to write you about. I am writing a biography of Sergei Eisenstein. […] I am wondering whether you would give me your assistance.”

At the beginning of her career, Seton, then a young arts correspondent with The Manchester Guardian, had developed an interest in the socialist movement. In 1932, she traveled to Moscow as a European correspondent for Theatre Arts Weekly. She became acquainted with a number of Soviet theater and film directors, developing an especially close relationship with Eisenstein. Seton was, Dana knew, particularly well qualified for the task she had taken on. She not only had a personal connection with Eisenstein but also a thorough understanding of his theories and artistic methods. Dana shared photos, stills, letters, documents, and newspaper clippings, and connected Seton to Leyda and Kraska.

Marie Seton visited Dana at Longfellow House in February 1950, after which she wrote:

Harry, I really enjoyed myself enormously staying with you for three days. I wish I could have just gone on staying. I cannot thank you enough for the help with material, which you gave me. It is of the very greatest value. I will care for it and use it to the utmost purpose.

On April 26, 1950, Harry Dana died in his sleep, like Eisenstein the victim of a heart attack. Marie Seton published her biography of Eisenstein in 1952. In her acknowledgments, she thanked the late H. W. L. Dana, who made important source material available to her shortly before his death.

Over the years, various films were made from Eisenstein’s Mexican footage. In addition to Sol Lesser’s 1933 Thunder Over Mexico, they include Death Day (1934), also released by Sol Lesser; Time in the Sun (1940), by Marie Seton; [19] a series of five educational shorts titled Mexican Symphony (1941), produced by Bell & Howell. In the mid-1950s, Upton Sinclair donated all the remaining Eisenstein footage to the Museum of Modern Art’s Department of Film. Then, in 1958, Jay Leyda compiled and released all the donated film material in a 255-minute feature titled Eisenstein’s Mexican Films: Episodes for Study. Finally, Eisenstein’s former assistant Grigori Alexandrov obtained access to the available footage and produced his version of Que Viva Mexico [sic] in 1979, and in 1998, another Russian filmmaker, Oleg Kovalev, created a documentary titled Sergei Eisenstein — Mexican Fantasy.

The story of Eisenstein’s Mexican-American journey poses a number of fundamental ethical questions about art production and mutual misunderstandings among passionate, thoughtful, good-hearted people in the face of a complicated historical situation. For Sergei Eisenstein and Harry Dana, the Mexican film became an incurable wound; for Upton Sinclair, a nightmare. Mary Craig Sinclair took a more philosophical approach:

With all our sorrow over it, I am glad it happened. I might have left the Socialists and gone to the Communists. But now I know that the end does not justify the means. I know that terroristic and underhanded intrigue is not for me. Communism makes too many rascals, or rather it gives too many rascals a chance to rationalize it.

In a letter to another friend, she reflected even more broadly: “Life is not an open book, and so we turn its pages by an excruciating effort and read — each according to his needs as well as according to his intelligence.”

¤

The author is deeply grateful to Linda Smith Rhoads for her invaluable advice on this article.

¤

Feature image: Marie Seton, Sergei M. Eisenstein: A Biography (London: Bodley Head, 1952), Illustration 33i.

¤

Angela Shpolberg is a resident scholar at Women’s Studies Research Center at Brandeis University and center associate at Harvard University’s Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies.

¤

[1] Harry M. Geduld and Ronald Gottesman, eds., Sergei Eisenstein and Upton Sinclair: The Making and Unmaking of “¡Que Viva Mexico!” (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1970), in which a number of the letters quoted in this essay are reproduced. For various perspectives, see, e.g., Marie Seton, Sergei M. Eisenstein: A Biography (London: Bodley Head, 1952), from which a good deal of biographical material in this essay is sourced; Ronald Bergan, Sergei Eisenstein: A Life in Conflict (Woodstock, N. Y.: The Overlook Press/ Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc. 1999); Anthony Arthur, Radical Innocent: Upton Sinclair (New York: Random House Publishing Group, 2007); and Masha Salazkina, In Excess: Sergei Eisenstein’s Mexico (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

[2] Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Dana, Additional Papers, 1914-1950, Correspondence, *2006MT- 125r, Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

[3] See Alfred Richman, “Serge M. Eisenstein,” The Dial (April, 1929), 311–314, and Mike O’Mahony, Sergei Eisenstein (London: Reaktion Books, 2008), 82–85.

[4] H. W. L. Dana, “Revolution in the World of Make-Believe,” Boston Evening Transcript, March 1, 1930, 6–7.

[5] Dana, “Revolution in the World of Make-Believe,” 2.

[6] “Rin-Tin-Tin Seems Interested,” Boston Herald, May 27, 1930.

[7] “Eisenstein Predicts New Type of Film,.” The Boston Globe, May 27, 1930.

[8] Clifford Howard, “Eisenstein in Hollywood,” Close Up (August 1930), 139.

[9] Howard, “Eisenstein in Hollywood,” 140–141.

[10] Louis Fischer, “Mass Movies,” The Nation (November 9, 1927).

[11] Donald T. Critchlow, When Hollywood Was Right: How Movie Stars, Studio Moguls, and Big Business Remade American Politics (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 19.

[12] See Mary Craig Sinclair, Southern Belle: A Personal Story of a Crusader’s Wife (New York: Crown Publishers, 1957).

[13] Mark W. Van Wienen, American Socialist Triptych: The Literary-Political Work of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Upton Sinclair, and W. E. B. Du Bois (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2012), 115–116.

[14] Anthony Arthur, Radical Innocent: Upton Sinclair, (New York: Random House Publishing Group, 2007), 231–32.

[15] “In Old Mexico,” The New York Times, September 25, 1933.

[16] Dario Gamboni, The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution (London: Reaktion Books, 1997), 144.

[17] H. W. L. Dana, “The New Eisenstein Film,” unpublished manuscript, in Dana, Additional Papers.

[18] The clips of the articles are preserved in Dana, Additional Papers.

[19] Seton bought 16,000 feet of negative for $3,500.00 from the Mexican Picture Trust. See the purchase contract, May 10, 1939, in Geduld and Gottesman, Eisenstein and Sinclair, 423–424.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

Alexander Kluge in Context

The value of "Toward Fewer Images" is its ability to unravel and disclose the conceptual richness of Alexander Kluge’s oeuvre.

Yuri Tynianov’s “Film — Word — Music” (1924)

Vera Koshkina and Ainsley Morse present “Film — Word — Music,” a 1924 essay on film by the great Formalist theorist Yuri Tynianov.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!