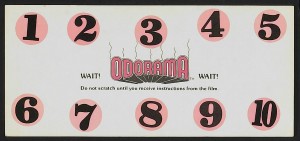

ON A MONDAY evening in October, New York City’s Film Forum screened the 1981 John Waters classic Polyester, in its original “Odorama.” A multisensory cinematic supplement in the form of a 10-compartment scratch-and-sniff card, Odorama directs film viewers through on-screen instructions to “smell on cue.” The opportunity to revisit this wondrous gimmick combining scent and screen was due largely to the New York run of Tab Hunter Confidential: The Making of a Movie Star. The documentary of this former heartthrob and Polyester star is based on Hunter’s autobiography and was directed by Jeffrey Schwarz, whose previous credits have earned him a reputation as something of a specialist in the chronicling of gay Hollywood. In both the book and the documentary, Hunter is upheld as a curious icon of the Hollywood studio-system’s decline, while the friction between Hunter’s sexual identity and his well-crafted celebrity is relayed to expose the sexually repressive protocols of Hollywood’s so-called Golden Age. Hunter’s 40-year career is described as one of continual ups and downs, in which his fierce desire for independence led him on a mostly failed pursuit for opportunities outside of his original studio contract — like in 1980, when Hunter, then working the regional dinner-theater circuit, was contacted by Waters to join the cast of Polyester, and the movie afforded him a short-lived comeback.

A charismatic and still-handsome 84-year-old, Hunter was on hand for a brief Q&A before the Film Forum screening of Polyester. He offered the audience generically affirmative kernels of wisdom about tenacity and self-acceptance, having retained the canned public persona of an Old Hollywood actor. Lines out of his memoir, re-delivered to his interviewer in the documentary were yet again repeated, including a favored zinger: “I’m sure I’ve kissed a hell of a lot worse,” when asked by Waters if he would mind kissing a “300-pound drag queen,” his Polyester co-star, Divine. In an unintentionally cruel attempt at tenderness for the actor he described as one of his favorite “leading ladies” — likening the reserved off-screen presence of Divine to a “beached whale” — Hunter proved a bit flat-footed when left to improvise his lines in person. Indeed, his Q&A performance highlighted the more disappointing aspects of both his autobiography and the documentary, which promised insights into the studio star system at the brink of its mid-1950s decline, but instead generates interest primarily through the actor’s good looks and the presence of his more famous celebrity friends, lovers, and peers.

Polyester, on the other hand, charts similar cultural coordinates with an incisive wit. Viewing the film in relationship to the renewed interest in cultural icons like Hunter, one finds in Polyester a sensitive and irreverent reflection on this transitional period in American cinematic history, still relevant to a contemporary audience. Whereas all of Waters’s previous projects bespoke a fragmentation of the American middle class and wielded his signature raunchy, trash aesthetic to deflate certain myths of the bourgeois family and sexuality, Polyester goes one step further to suggest a similar rearrangement of the American media landscape. He targets the space of the cinema as much as the stories presented therein. If Polyester is remembered as Waters’s first film to receive mainstream public acclaim, it is perhaps due to its ability to simultaneously assimilate and poke fun at the forms of cinema his work had previously stood apart from, a recognition that dominant filmmaking models provide an even wider set of materials for the creation of a strident trash cinema. Waters achieves this by upending the idealized conventions of the medium, incorporating signs of its obsolescence and displacement, and reveling in its essential promiscuity.

By 1981, the year of the film’s release, Tab Hunter had long since terminated his studio contract and had even fallen out of public favor, due, at least in part, to allegations of animal abuse (for which he was found innocent). Given this decline in visibility and reputation, his participation in Waters’s film as a leading love interest named Todd Tomorrow has an unmistakably ironical belatedness, signaling a deeply retrospective, if not nostalgic, dimension to the film. The incongruity between Hunter’s reputation as an actor and his role in the film is not simply one of untimeliness, but rather relates to earlier aspects of his career particularly apt for camp appropriation. Hunter exemplifies a type of celebrity formed primarily in the promotional orbit of the movie industry, rather than within the cinema proper — a stardom of the off-screen. As he himself writes in his autobiography, “It was these [fan] magazines that concocted my celebrity, completely out of proportion to my actual on-screen status.” By Hunter’s own account, magazine polls, gossip columns, and pop music singles served as primary vehicles for generating and preserving his fame, as important if not more so than his cherished vocation of acting. Hunter’s appearance on a 1957 episode of What’s My Line? as the mystery celebrity guest even suggests a possible inconsistency between the actor’s fame and his own sense of self. After revealing that he has recently produced a hit pop single, Hunter is asked by Martin Gabel whether he is better known for his singing than for his acting. Hunter’s negative response is immediately qualified by the show’s host, John Daly, who explains to the panelists, so as not to lead them astray, that while Hunter is currently better known for a number-one hit single (the saccharine “Young Love”), he did begin his career as an actor.

This misrecognition seems to play itself out again within Polyester. Reflecting on his casting in the film, Hunter said, “I’d helped ‘legitimize’ [Waters’s] brand of movie, and he made me ‘hip’ overnight.” While this might be partially true, Janet Maslin’s 1981 review of the film for The New York Times notes the “endearing” incompatibility of Hunter with the rest of his cast-mates, comprised primarily of Waters’s regular cohort of lovably coarse and mostly untrained stars: “Mr. Hunter seems not quite sure of what the rest of the cast is up to, and the other actors have a snappy, straight-faced manner he can't match.” Discarded by Hollywood and yet intimately bound to it, Hunter wields his outmodedness awkwardly, as though his industry credentials and Hollywood acting style prevent him from gelling convincingly in Waters’s unruly, fragmented universe.

However, it would be unfair and untrue to describe Hunter as a naïf. His personal account has moments of sharp and perspicuous reflection. Referring to yet another instance of the bad timing that seemed to plague his career, Hunter connects one of his film’s failures to its release around the time of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination: “In the wake of the president’s murder, and his murderer’s murder, everyone was staying home, waiting to see who’d be killed next on live TV. Nothing like this had ever happened before. Ticket sales weren’t brisk.” In spite of the litany of imperious industry representatives and competing actors that weave in and out of Hunter’s tale, a larger set of impersonal forces seem to structure the decline of his career and the “Old Hollywood, which [he] cherished.” A relocation of entertainment into the home and the increasing domination of broadcast television structurally transformed the movie industry. It is precisely this historical moment that forms the backdrop for Polyester.

The film tells the story of Francine Fishpaw, played by Divine, who struggles to keep up appearances of middle-class normalcy in spite of her cheating husband’s management of a pornographic cinema, her daughter’s boy-crazy delinquency, her son’s addiction to sniffing glue and psychotic fetish for stomping women’s feet, and her mother’s greedy cruelty. Abandoned by her family, hated by her neighbors, and humiliated by a local television crew, Francine descends into alcoholism, obsessively spraying aerosol room sanitizer to mask the ruinous conditions of her home life. On occasional shopping sprees with her newly enriched, former housekeeping best friend, Cuddles, Francine locks eyes with a handsome stranger. Eventually, at the scene of a deadly car accident, Francine meets the mysterious man, Todd Tomorrow, and the two begin a passionate romance, which is dashed when Francine discovers Tomorrow is in collusion with her mother to steal her money. After a gruesome finale, which leads to the deaths of Francine’s husband, her husband’s mistress, her mother and Todd Tomorrow, a conciliatory spray of aerosol deodorizer and a tender hug between Francine and her children signal a happy ending.

Every media form included in the film appears as a perversion: pornography has replaced family friendly entertainment; the nightly news sensationalizes fetishistic violence; even art cinema relies on gimmicks to attract its cinephile audience, offering trays of truly heinous-looking oysters on the half-shell at its concession stand. These media structure the lives of the Fishpaw family and mark an irrevocable distance between them and their Douglas Sirk prototypes.

Though based on the 1950s Sirkian melodrama, Polyester’s staging of an increasing entanglement between domestic life and media culture is responsive to the specific historical conditions of its release. While television most seriously threatened the primacy of the movie theater as the privileged location for cinematic spectatorship in the 1950s, an even wider set of video technologies exacerbated its displacement in the 1970s and early 1980s. Our own media landscape has witnessed the continued erosion of the movie theater as the privileged, collective setting of reception due to the increasing popularity of digital channels, especially with the rise in streaming services like Netflix. Faced with increasing competition, the movie industry has sought to preserve itself through techniques of further bodily incorporation, in the form of reclining seats and the return of 3D cinema. These apparatuses tend to lock the viewer into a more seamless and interpolative relationship to cinematic illusion, one prosthetically focalizing and enhancing vision and the other allowing the body to yield in prostrate acquiescence to the filmic flow. In spite of certain technophilic attempts to champion the new 3D cinema, these devices relate more to a history of movie gimmicks than they do to sincere attempts to reinvigorate the medium in the face of technological transformations. Polyester also relied on a ploy to lure people out of their homes and into the cinema, but utilized one that ultimately offers spectators a substantively different kind of film experience.

Recalling a longer history of failed efforts to combine scent and cinema, Odorama produces ironic effects similar to those of Hunter’s casting. Both represent outmoded systems of movie making, and take the form of media icons that circulated mostly in extra-cinematic spaces (children’s sticker books and hunky teen magazine foldouts, respectively). Both also tend to disrupt the continuity of the film. Unlike its predecessor, Smell-O-Vision, which phantasmagorically released scents into the cinema through the theater’s ventilation, Odorama insistently calls attention to its means of production. Introduced through a broken fourth wall monologue, viewers are instructed to scratch and sniff the appropriate circle at the sight of blinking numbers on screen. Pivoting from screen to card, the branding of Odorama in the form of a bright pink logo keeps the film’s silly technical support in constant view. Certain scents are scratched before their diegetic sources appear on screen, further splitting attention and forcing sensory experience to linger in the dark space of the theater. Moreover, this anticipatory activation risks inconsistent pay-offs. After certain scents were signaled, murmurs amongst audience members abounded. “Wait, what is that?” While scent is associated with certain intense corporeal responses (think smelling salts) and can serve as a powerful mnemonic trigger, it is also one of the least reliable sensory modes when decoupled from a fuller bodily perception.

Unlike 3D cinema, which tends to steadily enhance vision with its all-over stereoscopy, Odorama augments the somatic dimension of cinema through olfactory channels, only to undercut them. The pleasant smell of flowers or the stench of dirty sneakers disappoint, highlighting the flattening of experience when cheaply reproduced on a mass-scale. Other scents generate a more complicated interruption in the spectator’s involvement with the film’s narrative. The allure of new car smell is uncomfortably introduced just after scenes of an automobile wreck, disturbing the efficacy of this favored post-war cinematic fetish. The scent of glue, which in the film produces a dissociative response for Francine’s foot-stomping, drug-addled son, is almost unrecognizable in its simulated form. More interestingly, its reproduction literally divests the material of its remarkable affective properties, paradoxically offering an opportunity to get closer to the narrative universe only to mark an absolute distance.

In this way, Odorama demonstrates a consistent feature of Waters’s aesthetics. Over-flowing with desublimated appetite and fetishism — be it for cha-cha heels, foot stomping, the smell of cleaning products, or dancing — Waters’s work revels in confronting viewers with forms of desire they find repellent, or in interrupting the circuits of those they might seek to fulfill. Consider his 2009 sculpture, Rush, recently included in the 2015 Visual AIDS exhibition at La MaMa Galleria, “Party Out Of Bounds: Nightlife As Activism Since 1980.” Rush is a vastly oversized bottle of branded poppers tipped over next to an oil puddle representing its contents. Something like an Oldenburg thing or a Duchampian “delay” in PVC, plastic, and oil, Rush monumentalizes a prop of queer intimacies but neutralizes its erotic payoff, even intimating a certain melancholy in its pathetic disuse. Poppers, a solution of amyl nitrites, are recreational inhalants, which gained popularity at discos as a source of temporary euphoria and among gay men seeking more pleasurable sex. Sold in dark, opaque bottles, amyl nitrites are photo-sensitive chemicals and therefore remain unseen when used. This quality makes the arrangement of Rush all the more dampening in affect, its glistening pool signaling a breakdown in transmission and a degradation of efficacy. First exhibited at the Marianne Boesky Gallery in a show titled, “Rear Projection,” the sculpture ought to be seen alongside Waters’s other prurient media, as a sort of malfunctioning camera-less cinema.

Oscillating between sculpture (the bottle) and painting (the puddle), Rush bespeaks a breakdown of categorical security. The drug’s marketing history underscores that this uncertainty is not something effectuated merely at the level of artistic will, but may be intrinsic to poppers’ circulation in the world. The drug remains shrouded in a closeted doublespeak, many companies designating amyl nitrites as video equipment cleaners to mask their more intimate personal uses. These packaging feints, maneuvers to mediate between a public visibility and a private, subcultural practice, are quite similar to those adopted by actors like Tab Hunter. Both circulate as queer commodities made to “pass” through false advertising. Waters succeeds in his work by staging situations in which these figures appear in their full plurality. As Todd Tomorrow, Hunter returns to the screen to perform what at first appears to be an excessive portrayal of Hollywood heterosexuality, only to doubly frustrate his previous clean-cut image. Not only are his feelings for Francine unmasked as a predatory ruse to enrich himself, but his queerness is also always kept in view, since his love interest is, of course, a drag queen, whose performance simultaneously parodies the codes of Hollywood femininity and projects the physical vulnerability that defines Divine's legacy. In Rush and in Polyester, Waters’s work operates by subverting, deferring, or satirically exploding the mechanics of mediated eroticism through sheer excessiveness. As Odorama’s intimate activation and Rush’s duplicitous undecidability both stress, this is not a body of work that merely represents promiscuity; it is a body of work that is essentially promiscuous.

After its theatrical run, Polyester was reproduced and distributed on home video and edited for television broadcast. In both instances, the Odorama component was removed entirely. Waters has described this exclusion as a question of cost. However, the edit also underscores the specific cinematic contexts amenable to and targeted by the film’s gimmick. Seen with Odorama, Polyester demythologizes the movie theater setting by deranging its typical absorptive address. Too silly and too evasive to constitute an ethical stance or a fully fledged critique, the film signals the possibility for an alternative and, hopefully, queer cinema. It incorporates and celebrates seemingly outdated, inefficacious, and marginal features of the medium and insists that they remain potent conditions of possibility for a different kind of cinematic experience. This is a cinema borne by a disparate set of practices, ranging from the tactical silences of gay Hollywood icons, to the unseen and illicit pleasures of porn cinema audiences, to the retentive, re-mixing creativity of fannish adulation. It is a world offered up to us to be remade. Scratch and sniff the roses.

¤

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

Just Subtract Water: The Los Angeles River and a Robert Moses with the Soul of a Jane Jacobs

A reinvented Los Angeles River could act as both an urban spine and civic plaza, organizing and linking the communities it crosses.

Bloody Victoriana: On Crimson Peak

Marysia Jonsson and Aro Velmet review "Crimson Peak."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2015%2F12%2Fpolyester.jpg)