Mortal Republic by Edward Watts

THIS YEAR BEGAN with the United States enduring a 35-day partial governmental shutdown. The executive and legislative branches stood at complete loggerheads over the border wall issue, a standoff that put nearly a million Americans in financial jeopardy from missing paychecks and imposed an economic cost to the nation of an estimated $11 billion. After Congress finally spoke, and both houses passed a budget addressing border security, President Trump made an unprecedented end-run around Congress’s “power of the purse” by unilaterally declaring an “emergency” and reallocating funds to his pet border wall project. The question of Trump’s right to do so remains mired in the courts (although a recent Supreme Court decision allowed Trump’s reallocation of funds to go forward). For the moment, then, willful, unilateral fiat has “trumped” consensus and compromise.

Now, only half a year later, this episode has all but receded from memory. Yet, the underlying malady that led to that crisis remains with us. As this review goes to press, perhaps the gravest constitutional crisis of our times has arisen: a President who has challenged the very power of Congress to even conduct an impeachment inquiry — a direct challenge to an enumerated power given Congress under Article One of the Constitution and an unthinkable legal position until now.

A recent book on the fall of the Roman Republic reminds us that such signs of democratic dysfunction may be warnings of something more serious.

Edward Watts wrote Mortal Republic, he says, as a result of his efforts to explain to friends and family the parallels between the fall of the Roman Republic and the crisis of today's American democracy. In doing so, he may be boldly asserting an overarching thesis that other scholars would be reluctant to embrace (see for example, my interview with Mary Beard on her book SPQR). But Watts does not shy away from drawing parallels and asserting them to be worrisome. The Roman Republic did not have to collapse, he asserts. It happened for reasons that he takes pains to outline, relating them to the events emblazed in today’s headlines.

The Roman Republic and the American Republic share many points of structural kinship. Indeed, the Founding Fathers had their eye on the structure of the Roman Republic in crafting the federal government. Like ancient Rome, the American legislature has a Senate, essentially two ambassadors from each state, elected for six-year terms. As a populist balance to this inherently more conservative body, the Founders created a House of Representatives, elected every two years to better represent current opinion. In doing so, they borrowed directly from the structure of the Roman Republic, which was composed of a Senate, comprised only by members of the aristocratic (or patrician) class, and a Popular Assembly, representing the non-aristocratic (or plebeian) citizenry. Instead of a president, the ancient Romans elected annually two consuls, each of whom had veto powers over any new legislation. And to balance the powers of the consuls, the Popular Assembly elected tribunes of the People, also with veto power.

Through such a system of what we now call “checks and balances,” the Roman Republic, like the American Republic, was constructed to divide and share power between its institutions so that it would be less likely that one interest group could hijack the government at the expense of other actors. For that to work, Watts argues, a culture of compromise and negotiation was essential. And indeed, as he demonstrates in the opening chapters of Mortal Republic, such was the culture of the ancient Roman Republic, so that when ancient Romans appealed to the “common good,” it was not altogether disingenuous.

As Tacitus notes at the outset of his great history, Ancient Rome was first ruled by kings, who were expelled, according to legend, in 509 BCE, and the Roman Republic created. Watts does not go into the history of how the structures of the Roman Republic came into being; instead he starts his book taking the Republican structure as a given and begins this narrative as to how it unraveled. But there is also an interesting story behind the enfranchisement of the Roman working class. At first, the patrician class, through the Senate, held power while the non-patricians, or plebeians, were essentially disenfranchised. That came to an end in the fifth century BCE only when, in the face of the necessity to raise a new army to confront foreign hostiles, the plebeians literally went on strike, relocating en masse to one of Rome’s sacred hills. With essentially the entire working class on strike, the patricians had no choice but to give in and the Popular Assembly was born along with their Tribunes. From then on, and until the second century BCE, Rome’s patrician and plebeian classes shared power through their respective assemblies.

Ironically, Watts argues, it was Rome’s success in defeating its archrival, Carthage, and the subsequent aggrandizement of its territories and wealth, that set into motion events that would stress the Republic’s institutions. Rome (like Virgin Atlantic Airlines) always had upper and lower classes, but the influx of wealth from foreign wars along with a vast increase in the number of slaves (many of whom were at work on large farms), led to a breakdown in the social structure that had supported Republican Rome. The citizen farmer, which had been its backbone, could not compete with vast slave-run plantations. Land and wealth accumulated into fewer and fewer patrician hands. Landless Roman citizens congregated in the capital city without work and without money. The divide between rich and poor enlarged. Sound familiar?

By the second century BCE these trends had reached a critical point. Efforts to achieve land reform, led in succession by two brothers of the Gracchus family, went nowhere. Patricians blocked the efforts of the brothers to redistribute land to Roman citizens, and eventually in a patrician-led mob literally clubbed one brother to death in the Senate. His younger brother took up the cause of land reform only to meet a similar end. This, Watts writes, was a turning point Roman political history. Never before had an overt resort to violence been employed as a tool to settle a political dispute. After this, all rules were open to challenge.

Bit by bit, the norms that had governed the Republic fell away. Revered Republican traditions were broken again and again by the group (patrician or plebeian) seeking to advance its narrow interests. As the guard rails of Roman democracy weakened, the opportunity for an autocratic takeover increased. Sulla was the first to take advantage of the breakdown. This successful general had a loyal army at his command, and so he first staged a military takeover, then went about murdering political opponents, reconstituting the Senate to include only loyal patricians and erasing the powers of the tribunes and the Popular Assembly. In short, to put the autocrats back in power. His work done, Sulla retired and died of old age (although after a terrible disfiguring illness, some small justice in that).

Sulla may have thought that his counterrevolution had secured stability for the patricians, but he was wrong. The next hundred years featured a succession of rivalries between powerful figures also in command of their own loyal armies: Pompey, Crassus, and Julius Caesar. Efforts to restore the Republic — including the Popular Assembly — under leaders such as Cicero eventually came to nothing. At the end of the civil wars that rocked the Roman Republic during most of the beginning of the first century BCE, Julius Caesar finally emerged as an absolute ruler awarded by a craven Senate the title of “Dictator for Life” (in other words, king in all but name).

The paroxysm that followed Caesar’s assassination led to yet further civil wars between Caesar’s assassins and the pro-Caesar faction commanded by his heir and great nephew, Octavian, ultimately resulting in Octavian’s triumph over Republican forces, and then over his nemesis, Mark Antony. By 27 BCE, Octavian assumed the mantle of First Citizen (“Princeps”), avoiding the title of “king,” but clearly an absolute ruler in fact. Eventually the title of emperor (“Imperator”) would be awarded to him, and all Rome's rulers after that would bear this title. The Senate would continue to exist for centuries, along with many of the trappings of the Republican system, but all power was concentrated in the hands of Rome’s emperors.

As Watts warns, Rome’s collapse into an authoritarian government may indeed be a cautionary tale for the United States in the 21st century. Democratic institutions are the exception, not the rule, in the history of mankind, and the institutions that support such a government can be easily undermined. Juan Linz, a sociologist and political scientist at Yale, has argued that while America’s constitution has been much imitated, it has rarely worked outside of the United States itself. Beyond America, Linz argues, making the legislative and executive branches of government coequal has nearly always resulted in stalemate and political stasis. “The only presidential democracy with a long history of constitutional continuity is the United States,” wrote Linz in 1990. In the Age of Trump, one asks, is our legacy of constitutional continuity at risk?

Watts contends that stalemate was the undoing of the Roman Republic. The culture of finding solutions through compromise and negotiation eroded over the years until the various factions found themselves at such an impasse that no progress toward solving pressing social problems could be made. In such an environment of political paralysis, a strong man becomes (or appears to become) the only solution — a Sulla, a Caesar, and finally an Emperor Augustus. In the 20th century, a Franco, a Mussolini, and a Hitler.

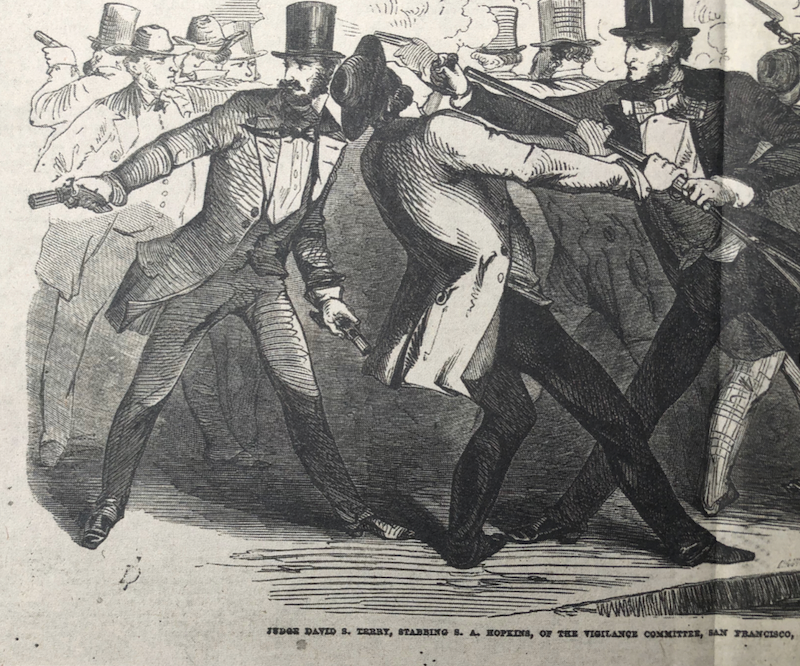

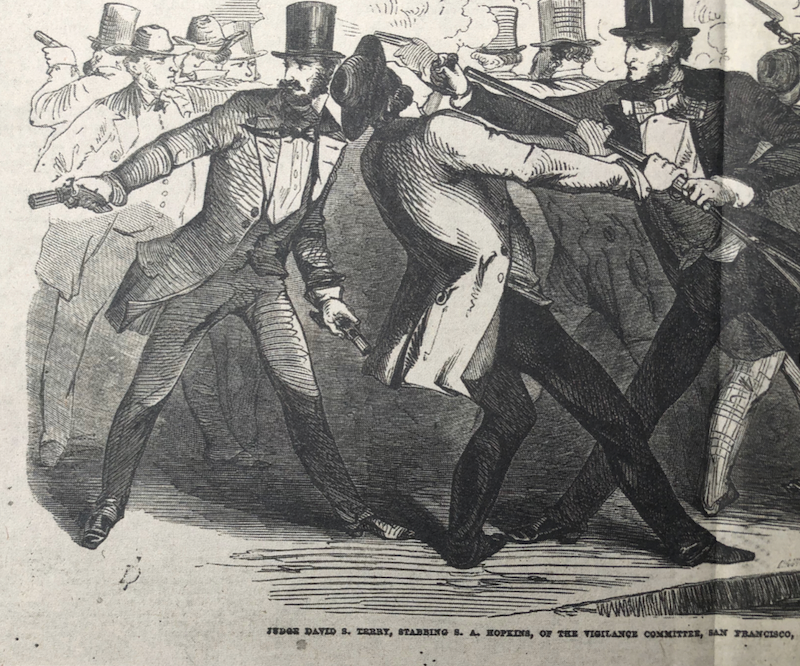

Are we in the United States at the same critical inflection point as the ancient Romans in the first century BCE? It is hard to deny that, in our lifetimes, the level of anger and the degree of polarization in today’s politics has never been as high. I suppose we can take some comfort that we have not yet come to mortal blows on the Senate floor, as did Romans, who finally settled intractable political disputes by assassinating opponents. Yet rancor of this level is not entirely unknown in American history. As documented in Joanne Freeman’s recent book, The Field of Blood, in the antebellum era leading up to the Civil War, Congress was scene to fistfights, canings, duel challenges, and even brandished weapons. That hasn’t happened yet in today’s Washington, and let’s hope it never does. But a parallel exists between the extreme antagonism of slave and anti-slave parties and the vitriol of our own factious political age. And we all know how things turned out in the debate over slavery — it took a bloody civil war to settle the question (although we still live today with the repercussions of slavery).

Watts’s Mortal Republic argues things did not have to turn out the way they did for the Roman Republic. Had the resort to violence to achieve political ends been condemned, had the loosening of the guardrails of Republican institutions been resisted, had good faith efforts been made to address and resolve critical social problems — even at the expense of narrow interests of accumulated wealth and power — had the culture of compromise and negotiation not eroded, Rome might well have maintained its republic into the Common Era.

Democracy, I have come to believe, is a fragile thing. It depends on a willingness to find consensus, the freedom to speak freely but also to listen to one’s opponents, to adjust one’s own views and take account of the concerns and interests of others. We’ve made it slightly over two centuries so far with the government created in Philadelphia in 1787. Will we make it to the end of this century? Or are we destined, like the ancient Romans, to collapse into an autocratic regime? The American system was once a model for new nations, but today some international leaders admire the stability of China’s autocracy over the chaos of America’s constitutional democracy.

The warnings of Mortal Republic should be heeded. We must recognize that when negotiation is seen as weakness, and compromise as surrender, the specter of an autocratic regime looms ominously.

Don Franzen is an entertainment lawyer based in Beverly Hills. He is also an adjunct professor at UCLA’s Herb Alpert School of Music teaching on the law and the music industry and the Legal Affairs editor for LARB.

Now, only half a year later, this episode has all but receded from memory. Yet, the underlying malady that led to that crisis remains with us. As this review goes to press, perhaps the gravest constitutional crisis of our times has arisen: a President who has challenged the very power of Congress to even conduct an impeachment inquiry — a direct challenge to an enumerated power given Congress under Article One of the Constitution and an unthinkable legal position until now.

A recent book on the fall of the Roman Republic reminds us that such signs of democratic dysfunction may be warnings of something more serious.

Edward Watts wrote Mortal Republic, he says, as a result of his efforts to explain to friends and family the parallels between the fall of the Roman Republic and the crisis of today's American democracy. In doing so, he may be boldly asserting an overarching thesis that other scholars would be reluctant to embrace (see for example, my interview with Mary Beard on her book SPQR). But Watts does not shy away from drawing parallels and asserting them to be worrisome. The Roman Republic did not have to collapse, he asserts. It happened for reasons that he takes pains to outline, relating them to the events emblazed in today’s headlines.

The Roman Republic and the American Republic share many points of structural kinship. Indeed, the Founding Fathers had their eye on the structure of the Roman Republic in crafting the federal government. Like ancient Rome, the American legislature has a Senate, essentially two ambassadors from each state, elected for six-year terms. As a populist balance to this inherently more conservative body, the Founders created a House of Representatives, elected every two years to better represent current opinion. In doing so, they borrowed directly from the structure of the Roman Republic, which was composed of a Senate, comprised only by members of the aristocratic (or patrician) class, and a Popular Assembly, representing the non-aristocratic (or plebeian) citizenry. Instead of a president, the ancient Romans elected annually two consuls, each of whom had veto powers over any new legislation. And to balance the powers of the consuls, the Popular Assembly elected tribunes of the People, also with veto power.

Through such a system of what we now call “checks and balances,” the Roman Republic, like the American Republic, was constructed to divide and share power between its institutions so that it would be less likely that one interest group could hijack the government at the expense of other actors. For that to work, Watts argues, a culture of compromise and negotiation was essential. And indeed, as he demonstrates in the opening chapters of Mortal Republic, such was the culture of the ancient Roman Republic, so that when ancient Romans appealed to the “common good,” it was not altogether disingenuous.

As Tacitus notes at the outset of his great history, Ancient Rome was first ruled by kings, who were expelled, according to legend, in 509 BCE, and the Roman Republic created. Watts does not go into the history of how the structures of the Roman Republic came into being; instead he starts his book taking the Republican structure as a given and begins this narrative as to how it unraveled. But there is also an interesting story behind the enfranchisement of the Roman working class. At first, the patrician class, through the Senate, held power while the non-patricians, or plebeians, were essentially disenfranchised. That came to an end in the fifth century BCE only when, in the face of the necessity to raise a new army to confront foreign hostiles, the plebeians literally went on strike, relocating en masse to one of Rome’s sacred hills. With essentially the entire working class on strike, the patricians had no choice but to give in and the Popular Assembly was born along with their Tribunes. From then on, and until the second century BCE, Rome’s patrician and plebeian classes shared power through their respective assemblies.

Ironically, Watts argues, it was Rome’s success in defeating its archrival, Carthage, and the subsequent aggrandizement of its territories and wealth, that set into motion events that would stress the Republic’s institutions. Rome (like Virgin Atlantic Airlines) always had upper and lower classes, but the influx of wealth from foreign wars along with a vast increase in the number of slaves (many of whom were at work on large farms), led to a breakdown in the social structure that had supported Republican Rome. The citizen farmer, which had been its backbone, could not compete with vast slave-run plantations. Land and wealth accumulated into fewer and fewer patrician hands. Landless Roman citizens congregated in the capital city without work and without money. The divide between rich and poor enlarged. Sound familiar?

By the second century BCE these trends had reached a critical point. Efforts to achieve land reform, led in succession by two brothers of the Gracchus family, went nowhere. Patricians blocked the efforts of the brothers to redistribute land to Roman citizens, and eventually in a patrician-led mob literally clubbed one brother to death in the Senate. His younger brother took up the cause of land reform only to meet a similar end. This, Watts writes, was a turning point Roman political history. Never before had an overt resort to violence been employed as a tool to settle a political dispute. After this, all rules were open to challenge.

Bit by bit, the norms that had governed the Republic fell away. Revered Republican traditions were broken again and again by the group (patrician or plebeian) seeking to advance its narrow interests. As the guard rails of Roman democracy weakened, the opportunity for an autocratic takeover increased. Sulla was the first to take advantage of the breakdown. This successful general had a loyal army at his command, and so he first staged a military takeover, then went about murdering political opponents, reconstituting the Senate to include only loyal patricians and erasing the powers of the tribunes and the Popular Assembly. In short, to put the autocrats back in power. His work done, Sulla retired and died of old age (although after a terrible disfiguring illness, some small justice in that).

Sulla may have thought that his counterrevolution had secured stability for the patricians, but he was wrong. The next hundred years featured a succession of rivalries between powerful figures also in command of their own loyal armies: Pompey, Crassus, and Julius Caesar. Efforts to restore the Republic — including the Popular Assembly — under leaders such as Cicero eventually came to nothing. At the end of the civil wars that rocked the Roman Republic during most of the beginning of the first century BCE, Julius Caesar finally emerged as an absolute ruler awarded by a craven Senate the title of “Dictator for Life” (in other words, king in all but name).

The paroxysm that followed Caesar’s assassination led to yet further civil wars between Caesar’s assassins and the pro-Caesar faction commanded by his heir and great nephew, Octavian, ultimately resulting in Octavian’s triumph over Republican forces, and then over his nemesis, Mark Antony. By 27 BCE, Octavian assumed the mantle of First Citizen (“Princeps”), avoiding the title of “king,” but clearly an absolute ruler in fact. Eventually the title of emperor (“Imperator”) would be awarded to him, and all Rome's rulers after that would bear this title. The Senate would continue to exist for centuries, along with many of the trappings of the Republican system, but all power was concentrated in the hands of Rome’s emperors.

As Watts warns, Rome’s collapse into an authoritarian government may indeed be a cautionary tale for the United States in the 21st century. Democratic institutions are the exception, not the rule, in the history of mankind, and the institutions that support such a government can be easily undermined. Juan Linz, a sociologist and political scientist at Yale, has argued that while America’s constitution has been much imitated, it has rarely worked outside of the United States itself. Beyond America, Linz argues, making the legislative and executive branches of government coequal has nearly always resulted in stalemate and political stasis. “The only presidential democracy with a long history of constitutional continuity is the United States,” wrote Linz in 1990. In the Age of Trump, one asks, is our legacy of constitutional continuity at risk?

Watts contends that stalemate was the undoing of the Roman Republic. The culture of finding solutions through compromise and negotiation eroded over the years until the various factions found themselves at such an impasse that no progress toward solving pressing social problems could be made. In such an environment of political paralysis, a strong man becomes (or appears to become) the only solution — a Sulla, a Caesar, and finally an Emperor Augustus. In the 20th century, a Franco, a Mussolini, and a Hitler.

Are we in the United States at the same critical inflection point as the ancient Romans in the first century BCE? It is hard to deny that, in our lifetimes, the level of anger and the degree of polarization in today’s politics has never been as high. I suppose we can take some comfort that we have not yet come to mortal blows on the Senate floor, as did Romans, who finally settled intractable political disputes by assassinating opponents. Yet rancor of this level is not entirely unknown in American history. As documented in Joanne Freeman’s recent book, The Field of Blood, in the antebellum era leading up to the Civil War, Congress was scene to fistfights, canings, duel challenges, and even brandished weapons. That hasn’t happened yet in today’s Washington, and let’s hope it never does. But a parallel exists between the extreme antagonism of slave and anti-slave parties and the vitriol of our own factious political age. And we all know how things turned out in the debate over slavery — it took a bloody civil war to settle the question (although we still live today with the repercussions of slavery).

Watts’s Mortal Republic argues things did not have to turn out the way they did for the Roman Republic. Had the resort to violence to achieve political ends been condemned, had the loosening of the guardrails of Republican institutions been resisted, had good faith efforts been made to address and resolve critical social problems — even at the expense of narrow interests of accumulated wealth and power — had the culture of compromise and negotiation not eroded, Rome might well have maintained its republic into the Common Era.

Democracy, I have come to believe, is a fragile thing. It depends on a willingness to find consensus, the freedom to speak freely but also to listen to one’s opponents, to adjust one’s own views and take account of the concerns and interests of others. We’ve made it slightly over two centuries so far with the government created in Philadelphia in 1787. Will we make it to the end of this century? Or are we destined, like the ancient Romans, to collapse into an autocratic regime? The American system was once a model for new nations, but today some international leaders admire the stability of China’s autocracy over the chaos of America’s constitutional democracy.

The warnings of Mortal Republic should be heeded. We must recognize that when negotiation is seen as weakness, and compromise as surrender, the specter of an autocratic regime looms ominously.

¤

Don Franzen is an entertainment lawyer based in Beverly Hills. He is also an adjunct professor at UCLA’s Herb Alpert School of Music teaching on the law and the music industry and the Legal Affairs editor for LARB.

LARB Contributor

Don Franzen is a lawyer in Beverly Hills specializing in entertainment and business law. He has lectured on entertainment law at the Eastman School of Music, Santa Monica College’s Academy of Entertainment and Technology, the Berklee School of Music in Valencia, Spain, and lectures at UCLA’s Herb Albert School of Music, where he teaches two courses on the law and the music industry. He has published articles on legal issues in newspapers, magazines, and law journals. He serves on the board of the Los Angeles Opera and counts among his clients leading performers in opera, orchestral music, film, and the recording industries. He is the legal affairs editor for Los Angeles Review of Books.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Emperor and the Empty Tomb: An Ancient Inscription, an Eccentric Scholar, and the Human Need to Touch the Past

Is the Nazareth inscription the oldest artifact of Christianity? A mysterious document and an eccentric scholar hold the clues.

Democracy Versus Liberalism

Roslyn Fuller considers Josiah Ober's "Demopolis: Democracy before Liberalism in Theory and Practice."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2019%2F10%2Fmortalrepublic.jpg)