My mother was originally given six weeks to live. In the first of those, we drove her to doctor after doctor, all of whom repeated this news somberly but otherwise without affect. In the meantime, my mother’s pain was getting worse by the day. She was prescribed Oxycontin around the clock, but it was already losing its effectiveness. I didn’t want her to have to sleep alone — I couldn’t imagine what thoughts would plague her — so I slept with her in the king-sized bed where we used to watch Law & Order reruns when I got home late from a date. But I also didn’t want my partner to have to sleep alone because he too was terrified, so I decided we would all sleep together with me in the middle. A doctor’s recommendation of morphine patches helped my mother get through the night while we lay around her, paralyzed in a hot panic.

My husband and I are both artists, although in those years I also maintained what I liked to refer to as my “day job” as a film professor at a small liberal arts college. Before my mother’s diagnosis, I was in the midst of making a particularly energetic suite of abstract paintings — my best at the time. My husband had taken out enormous loans to pursue his MFA in sculpture at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. We were both commuting several hours in different directions from our apartment, which was just across the river from Manhattan. Daily existence had its difficulties, but our lives were rich. I had just turned 30 a few months prior, and had been surprised to find myself satisfied and even a little delighted at my own sense of accomplishment.

Everything changed when my mother got sick. In the haze of those first anxious nights, my dreams shattered: my mother was going to die, and art wasn’t going to save us. After a few sleepless hours, David would slip out of bed, go downstairs, make a pot of coffee, and search online for medical schools that might admit wayward Conceptual artists directly to their programs. (There were none.) During my own bouts of insomnia, I researched cancer trials and obsessed about the hopeless statistics of the disease. We were each searching for ways to overcome the overwhelming feeling of helplessness. There was no good news.

Day and night I looked at my mother’s face and her deeply veined brown hands. I wasn’t accustomed to gazing at her with the attention of a lover or an autopsist, but in those days I studied the way her thin, elf-like ears poked through her pin-straight hair, and her collarbone scooped deep, graceful pools in the space beneath her shoulders. In a few more weeks, I couldn’t help thinking, I am never going to see this face, these hands, these ears, this collarbone, again. Her imminent loss was unbearable, but I knew I must try to savor the last days we had together. And so I held her, I massaged her, I walked with her, I cooked for her, I washed her, and then, when she requested, I disposed of her untouched food and gave her more painkiller.

One night, in an otherwise tortured episode of internet self-flagellation, I discovered a doctor. Or rather, a program devoted to treating pancreatic and other incurable cancers. We couldn’t get an appointment with the star doctor whose beaming face I saw on the website, but we did manage to get one with someone else, supposedly working in the same unit. The appointment was two weeks away. On the phone, I begged them to make it sooner, but it was August and as everybody else in New York already seemed to know, all doctors go on vacation in August, so it is only logical that nobody gets sick and dies during that month. I didn’t know how my mother would make it to the appointment. Somehow she did.

The waiting room in Columbia Presbyterian’s oncology unit was standard enough, but the doctor’s office was an absolute wreck. The desk, chairs, windowsill, and floor were all piled high with garbage: patient records, ancient faxes, encrusted take-out containers, and god knows what else. The man who sat before us was older, impish, and rude. His eyes were blood-shot, his teeth yellow, and his skin a palimpsest of differently colored flesh patches. As was her custom when meeting important people, my mother dressed to the nines. He was not only unkempt but looked like he was in urgent need of medical care.

As I had learned to do, I had prepared a list of questions. When I started asking them, he became impatient, and started juggling odd objects on his desk. I don’t mean just fidgeting: he was literally throwing several things in the air at once and trying to catch them. Whereas he seemed uninterested in my mother’s diagnosis, he seemed extremely intent on figuring out a technique of keeping three pieces of junk airborne simultaneously. My mother and I exchanged an ironic glance: who was this nutjob? Then he asked to see my mother’s X-rays, which we had carried along in the sheath of medical paperwork she had already accumulated. He didn’t have a lightbox anywhere in the room — was this dump even a hospital? — so he pulled the transparent sheet out and held it up to a filthy window overlooking the Hudson. There were my mother’s organs, inscrutable clouds of peril, barely illuminated in the dusty light.

The doctor’s beady eyes squinted as he angled the X-ray this way and that trying to get a better look. Suddenly the image caught the light, and his interest piqued.

“What do you mean she’s inoperable?” he demanded.

“Well, that’s what all of the doctors said,” I told him.

“Did they even look at the X-ray?”

I had to think a minute. No, they hadn’t. Each one had just read the original doctor’s report. My heart started pounding.

“Well, I think we might be able to operate,” he said after a few moments of quiet deliberation. “Then we’ll do chemo and radiation.”

“Will that save my mother?” I blurted out.

“I have no idea,” he replied just as bluntly. “But we’re all going to die anyway. Some of us sooner rather than later. In the meantime, why don’t you try to eat something?” he sarcastically asked my mother. “You look like a skeleton.”

A few minutes later, we left the stinking pit of his office with an appointment to see the surgeon when she returned from vacation. “What kind of lunatic have you taken me to?” my mother demanded.

“That’s our man,” I said, beaming. For in the instant that his hideous face had been illuminated by the late afternoon sunlight streaming through that neglected X-ray, my disgust had transformed into adoration. I loved everything about him, from his awful skin to his inappropriate juggling.

The story doesn’t end there. In many ways, it just begins.

My mother died in December 2009, the same year that I moved to Canada and started teaching at McGill University. But she ended up dying later rather than sooner as the doctor had intimated, two and half years later, to be exact. In those two and a half years, I became more intimate with my mother than I have ever been with another human being. When she went up the chimney, a tremendous part of me went with her.

What remains of me struggles to compose my thoughts on the relationship between intimacy, loss, motherhood, and artistic production. I’m just past my 40th birthday, and three weeks away from giving birth for the first time after being pregnant for five. In my present state, it is impossible for me to write objectively. If I write somewhat urgently now, it is because I am writing both as Enid’s daughter, and as a person on the verge of becoming someone's mother.

Before my mother’s illness, my life was split between my vocation as a film scholar, and my avocation — is it merely that? — as an abstract painter. I spent Tuesday through Thursday professing in Pennsylvania, and Friday through Monday painting in New York. I relied on painting to provide a release for the chaos that raged inside of me, while I spent the days of my professional life teaching, writing, and otherwise drowning in a sea of words. The gestural marks of abstraction helped me to articulate the waves of feeling that exceeded — or at the very least resisted — language. Hackneyed as the heroic myth of Action Painting may be, there is something about the visceral nature of staining, throwing, and pouring paint that provides an outlet for embodied intensities not easily contained in pictures of people and places and things.

While abstract painting provided an intimate record of my own body’s gestures and impulses, it was less capable of teaching me how to cope with the nuances of love and loss than the great masterpieces of cinema. And yet when my mother got sick, I couldn't help but feel that most cinematic “stories” about loss were just that: stories. However moving they might be, they seemed to stagger under the weight of their own clichés. How, after all, could one sidestep the inevitable denouement of every story: “And then she died.”

¤

As my mother’s pain intensified, I discovered that neither cinema nor painting eased the difficulty of watching her suffer. As her full-time caretaker, I had no time to paint. Nor could I bear film’s well-choreographed histrionics. I used to pride myself on my relative immunity to the manipulations of popular culture, but in my current state, even a cheesy opening montage could reduce me to cataclysmic weeping. Besides, none of the pictures I glimpsed offered any answer to the urgent question the universe had suddenly posed: How was it possible to maintain a self when confronted with a loved one’s imminent loss?

One of the things I discovered in my own idiosyncratic journey through loss is that visual art cannot easily represent what you can’t see. While some of the most innovative artists have attempted to make the ineffable visible, at its most profound level, intimacy defies representation. This may be due to its essentially performative and interactive nature. After all, how else does intimacy manifest but in a series of banal gestures, all of which are meaningless in themselves, and unreadable to others? Perhaps this is why representing intimacy onscreen can be even more difficult than representing sex or death. While one’s own experience of intimacy may share certain cultural features with another’s, it is ultimately born of our own unique experiences. Carved from the flesh of the world but scarred by the ravages of our own particular histories, something essential about each of us remains impenetrable even in the most acute moments of corporeal violation. Our deepest relations to others are even less transparent.

As a philosophical concept, intimacy has sometimes been criticized as a “retreat from worldliness,” or evidence of the “shrinking of experience.” However, I’ve always believed something quite different: that intimacy, however fraught, may in fact be the most effective conduit for opening ourselves up to a more expansive engagement with the world. Yet not all artists take utopian approaches to the challenges of representing intimacy. Rather than inviting us to enter into tactile communion with the image, certain filmmakers forge acute experiences of intimacy by shutting us out, or by withholding our access to the body in the frame. In their films, the cultivation of disorienting disjunctions between sound and image foregrounds the inextricability of intimacy and alienation. For if the shrinking of experience is fundamental to our experience of intimacy — as it was during the isolating years I spent caring for my mother — then perhaps we must figure out how to use this sense of contraction to support rather than impede the personal and collective challenges that are everywhere around us.

The single most important lesson that I learned since my mother’s death is that not all forms of intimacy pivot around bodily presence. Sometimes intimacy is defined by and constituted through loss. As a film scholar, I cannot help but wonder: how can visual media convey the intimate presences that constitute empty spaces? Nowhere at all, my mother is everywhere with me. No one has been as happily haunted as I — but cinema cannot capture what the human eye can’t perceive.

And yet, absence is, in some ways, the basis of cinema’s imaginary form of signification. Illuminating phantoms on the screen, cinema vivifies what isn’t there. Like the photograph, which film theorist André Bazin famously compared to a fingerprint because of its “indexical” or forensic relation to the thing photographed, the camera captures nothing more than a ghostly impression of the bodies that pass briefly before its lens. These corporeal traces have the potential to palpate us toward a sense of closeness with bodies that are, as Roland Barthes reminds us, temporally alien and irretrievably lost.

In his magnificent book Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, Barthes emphasizes the delayed temporality of such forms of photographic intimacy: “From a real body which was there, proceed radiations which ultimately touch me, who am here, the duration of the transmission is insignificant; the photograph of the missing being, as Sontag says, will touch me like the delayed rays of a star.” Intimacy is thus built into photographic media — and simultaneously denied by it. In the world of images, intimacy cannot manifest except as a stain in the field of the visible.

Later in the same slim volume, Barthes insists that all photography invokes the catastrophe of mortality when he writes, “each photograph always contains [the] imperious sign of my future death.” In a similar vein, I would argue that intimacy invokes the catastrophe of loss. To allow oneself to become intimate with another is to invite them to leave their mark on us. It is also, however, to surrender to the certainty of loss.

When my mother was dying, I begged my husband to record her. Under the circumstances, neither of us had the audacity to stick a camera in her face. The one time we did manage to record her, I wanted to spare her the indignity of pretending to “be herself” on camera at a time when she could barely manage to “be herself” off of it. It has been over nine years since that tape was made, but neither my husband nor I have been able to look at it since. I avoid my mother’s moving image as one avoids the plague. But what am I afraid of contracting? I suspect that the image of her illusory vitality, transformed into yet another one of cinema’s imaginary signifiers, would be too intolerable. At this point, I’ve come to prefer the bronze box that contains her ashes, which I keep beside my bed. It is cold and motionless and it doesn’t promise what it can’t deliver. Within weeks of picking it up from the crematorium, my sister and I had kissed off its supposedly untarnishable patina. The box has become verdant with our efforts to revive her, but still she refuses to bloom.

Like the baby I carry within me, my mother is invisible, sealed off in an impenetrable container. The more I think about it, the more I come to believe that my mother and the baby are suspended in parallel states, moving at different speeds toward and away from being. I sleep fitfully at night, entangled in a damp chain of flesh that bridges past, present, and future. I am obviously in the process of losing my mind, which is to say, becoming a mother.

¤

Coaxing one’s mother out of the box and into the frame is no easy task. As Barthes mused while searching for a “just” photograph of his mother after her death, “I never recognized her except in fragments.” Although he claims to have finally found a photograph of his mother taken when she was five years old that provides a glimpse of the woman she became, he does not include it in what is otherwise a copiously illustrated volume. There is nothing for anyone else to see there. Yet I’ve never even managed to find a single image of my mother as a child in which I can recognize a spark of who she would become. When I asked a long estranged friend of hers from childhood, “What was she like when she was little?” He responded, “Your mother? She was never little.”

As an artist, intimacy can be an incredible catalyst for making work, but it can also be a formidable obstacle. Tasked with care for the dying, neither my husband nor I could make art during the period of my mother’s illness. The intensity of our experience not only cut us off from the rest of the world, as Hannah Arendt warns of intimacy, but also cut us off from our own abilities to express ourselves. The last painting I made, in the bedroom my mother vacated after she could no longer climb the stairs, was an explosion of color and emotion. Sensing I would never paint so exuberantly again, I put everything into it, calling it The Last Euphoria. But the painting was a lie, for those feelings of euphoria had already vanished, dissipated in a single instant. In the 10 years since, I’ve never felt such ecstasy again. Yet within this same interval, I discover that intimacy takes other shapes than euphoria.

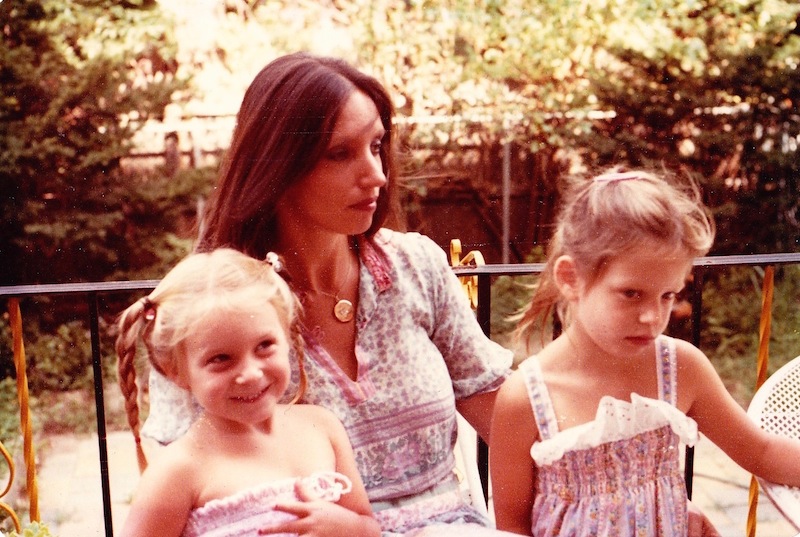

Several years after my mother died, I tried to paint a portrait of her in order to capture some glimpse of the renegade forms of intimacy that persist after loss. I am not a figurative painter so this represented a significant departure from my usual practice. So I turned to a photograph taken of her, my sister, and me when I was about three or four years old.

We are posed on the back terrace of my childhood home in Brooklyn. The ’70s have just ended, and the leaves of spring spangle the new decade like a thousand humming lights. We are all wearing sundresses swirling with soft pink, blue, and lavender flowers. I am the only one smiling, a wide idiot grin. My sister’s eyes are downcast. She is only a little girl, but already she has grown into the shape of a sadness from which she will never depart.

My mother stands between us, gazing deeply away. Her unseen fingers rest upon us, two small, needy bodies binding her to this world even as her thoughts have departed it. Her skin is the color of pale terracotta, her hair a shiny brown curtain. She is wearing a ’60s peasant dress made of thin flowered gauze that even as children my sister and I fought over in anticipation of her disappearance. A big gold locket lies flat on her taut, burnished chest. The dress will go missing years before either of us can inherit it, and I will flatten my body into a tiny disc and hide myself in that golden locket so that even in her absence, I can hang from her neck and study her secrets through its diamond eye.

For two months, I squint at the photo and then back again at the canvas, a tiny brush poised in my hand as I try to transpose the spirit of my mother from one frame to another. But the photograph is blurred and old and insufficiently detailed. I am aware that I can use a scanner to blow it up and really inspect it, but such careful, mediated scrutiny of the image will no more yield my mother’s spirit than the rub of a genie’s lamp. In the end, I cannot retreat from the golden locket long enough to complete an image of my mother’s image. The image is “just” — but still she appears only in fragments. Despite my best efforts, I cannot make her whole again.

How then do we visualize the forms of intimacy that persist, like an unrelenting stain, after the rhapsodies of corporeal entanglement cease? Is it possible that we can only recognize such intimacies when we see them? Or rather, when we feel them? Confronted with Arshile Gorky’s haunting portraits of his mother, whom he witnessed starve to death during the Armenian genocide, I am struck with the pathos of the forever lost. Working with a single photograph taken when he was eight years old, before he migrated to the United States without her, Gorky obsessed over the painting of his mother, which he attempted on and off from 1926 until 1942, before committing suicide in 1948. In “The Artist and His Mother,” the artist’s retrospective act of mourning ossifies in the mother’s idealized alabaster facade. Her face is an eternal mask, her body nothing more than a collection of abstract forms and shapes. This is not the “particular” mother whose death Barthes mourns — the mother Barthes had the privilege of living with for most of his adult life — but the Universal Mother who has been snatched from the flow of time by the forces of History. Although mother and son are captured in the same frame, we can see the child leaning forward into the future, while the mother retreats into the past. His face bears the dark and flushed tone of the living, while hers has the bloodless aura of an apparition. In this image, Gorky captures his mother in the process of disappearing. Although the little boy in the photograph was as lost to Gorky as his dead mother, the image is a self-portrait of his own tentative survival, as much as it is a portrait of his mother’s mortification into memory.

When I finally succeed at completing a painting of my mother, years after my first post-mortem attempt, I realize that I, too, have turned her into a statue, eternally suspended in the alabaster folds of time. In turning her into an image, I have tossed her outside the realm of relationality, absenting the image of my own childhood self in the process. This is not an image of intimacy but of worship. Neither of us can survive the transmutation from flesh into icon.

This portrait of my mother, which I began last Mother’s Day, is suffused with the yearly ritual of grief and compounded by my devastation over three recent miscarriages. I couldn’t help but feel that in losing the capacity to mother someone else, I was in the process of losing my mother all over again. Yet even in the midst of such grim musings, I could not help but recall a painting I did of my mother while I was still a teenager, which she admired, and persisted in referring to as her “self-portrait” until her death. I was always delighted by this slippage, for in her unintentional malapropism, my mother communicated an elusive truth about the inextricable bond between us. While it is certainly true that one need not procreate to carry the other within us, this fact alone does not answer my question: how does one maintain a self when losing an other who is also our “self”?

¤

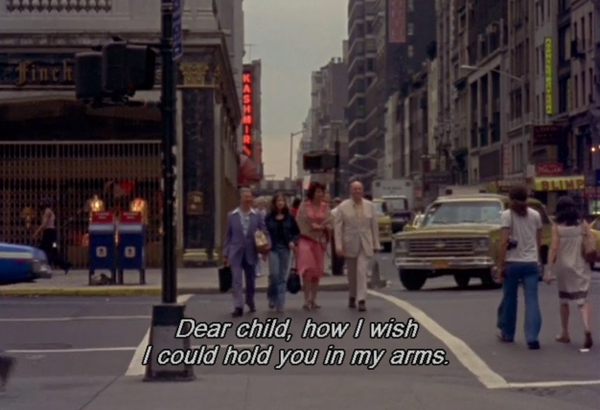

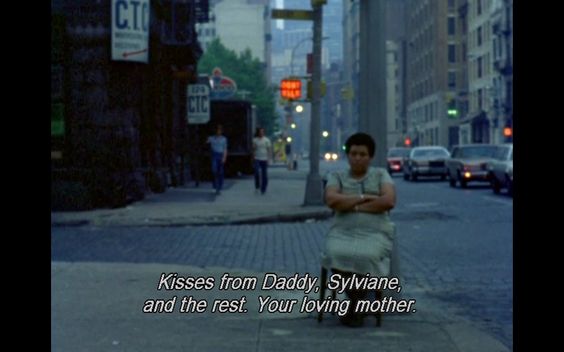

This is one of the many questions posed by Belgian director Chantal Akerman’s films about her mother. Suffused with the pathos of maternal longing, News from Home, which Akerman shot in New York City in 1976, explores the way the presence of a loved one can be carried even in spaces defined by absence and displacement. Akerman had moved to New York in 1971 at the age of 20, and stayed until 1973, at which point she returned to Belgium and soon went on to achieve international renown for her groundbreaking feminist film Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975). News from Home is composed entirely of long takes of urban vistas, accompanied by a voice-over in which Akerman reads letters that her mother sent her during her sojourn in New York. Yet the film is neither a portrait of a forsaken mother nor a portrait of a wayward daughter. Rather, it is a portrait of how intimacy tunnels deep beneath the surface of placid facades to flourish in the ellipses of what cannot be expressed.

In many ways, News from Home is a minimalist autobiographical film, deeply influenced by the structural films of experimental filmmakers such as Hollis Frampton and Michael Snow, many of whom Akerman had met while hanging out in downtown Manhattan around the Anthology Film Archives. Documents of a most unlikely ghost town, Akerman’s urban compositions of New York City frequently feature streets, parking lots, and subway platforms bereft of people.

In several scenes in the second half of the film, we do glimpse anonymous passersby or cars full of subway riders — some of whom glare menacingly at the camera and presumably, the young women behind it, and others who seem, like ordinary New Yorkers, not even to notice.

But never once do we see Akerman or her mother. The film disappears both of them, although there is a moment in which one wonders whether it is the filmmaker’s reflection, or perhaps that of her cinematographer Babette Mangolte, which appears in the glass of a subway car as it tunnels through the dark space of New York’s underground.

As for Akerman’s mother, she is never so much as glimpsed in the frame. Nor are we privy to what Barthes describes as the “grain” of her voice, which we never hear. Read in a near monotone in Chantal’s much-younger voice, Natalia Akerman’s letters are exquisitely banal, exhausted documents that say nothing and everything about what it means to love someone.

She describes days at work in which “nothing happens,” relates the uneventful gossip of friends and neighbors, and wonders why her daughter doesn’t respond more frequently to her letters. When she does receive a letter from Chantal, she rejoices as if the Messiah himself has written, only to move on, moments later, to express her frustration that her daughter never answers any of her questions, which are embroidered in blunt pattern across the duration of the film. Where is she living? Why doesn’t she ever say how she really is? Did she ever receive the $20 that her mother sent through the mail? You don’t need a Jewish mother to recognize the way that love inheres in such persistent nagging.

But is there a subtext to this text? Must there be? Or is it possible that all the meaning that there is inheres in the banality of these notes and impersonal landscapes? Could intimacy be no more than a collection of banal inscriptions and mundane misrecognitions exchanged between lovers in the inevitable retreat from corporeal proximity? Or an invisible stain that haunts an empty street corner?

Throughout all her mother’s gentle harangues, Chantal Akerman offers nothing in her own words. Apparently, these anonymous images of isolated street scenes are the only news that the filmmaker has to report. “When we are home,” critic Svetlana Boym writes hopefully, “we don't need to talk about it.” But this sense of sufficiency doesn’t account for Akerman’s silence. As the inaugural ambiguity of the film’s English title suggests, neither Chantal nor Natalia (Nelly) Akerman were ever really at home in either Brussels or New York. Natalia Akerman was a Polish-born Jew who moved to Brussels in 1938 in the hope of avoiding the Nazis. In 1942 or 1943, she was forced back to Poland, where she was imprisoned at Auschwitz for 18 months. In one of history’s cruel ironies, Auschwitz was only 30 miles from where Nelly had grown up, outside of Krakow. Chantal Akerman was born after the war, in Brussels, in 1950 to parents who had lost most of their families during the war.

How is the meaning of “home” irrevocably altered through generations of displacement and trauma? Under such circumstances, can “home” ever describe anything more than a perpetual sense of homelessness that has become so familiar, so intimate, that one comes to recognizes it as being essential? Although the film never explains the crucial biographical details that suffuse its longings, certain elements intimate the conditions of exile that shape and define the film’s sense of alienation. For instance, the film’s odd bilingualism — the title is in English, but the letters are read in French — not only recalls the double consciousness of the refugee, but also the way in which any nostalgic attempt to conjure home becomes tangled in the inevitable quagmire of translation. “When we start speaking of home and homeland,” Boym writes, “we experience the first failure of homecoming. How does one communicate the pain of loss in a foreign language? Why bother?” she asks. Akerman doesn’t.

But News from Home does manage to suggest the ambivalent experience of exile in other ways. After all, to intimate is “to communicate with a hint or other indirect sign.” Indeed, the condition that Boym describes as “diasporic intimacy” knows no other way. As Boym writes,

Diasporic intimacy can be approached only through indirection and intimation, through stories and secrets. It is spoken of in a foreign language that reveals the inadequacies of translation. […] [It] does not promise an unmediated emotional fusion, but only a precarious affection — no less deep, yet aware of its transience […] it is rooted in the suspicion of a single home, in shared longing without belonging.

Yet if News from Home is, like diasporic intimacy, “haunted by the images of home and homeland,” then “it also discloses some of the furtive pleasures of exile.”

In News from Home, the anonymity of the often-depopulated urban scenes forms a crucial counterpoint to the devastating familiarity of the letters. For anonymity and intimacy are not opposites, but the strange bedfellows of exile. When we look at the images that Akerman’s camera captures, they appear at first as scenes of alienation. And yet, when one is adrift in the world, one often feels most at home in such alien vistas.

Intimacy is thus not about a retreat from worldliness, but a transformation of the strangeness of the world into something that feels familiar — or a familiarity that despite the estrangement of dislocation, persists like a stain. In such a world, it is not so unusual to “sonder” beneath the surfaces of the metropolis’s impersonal architecture to discover that “each random passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own.”

And thus Akerman’s film begins to map the

epic story that continues invisibly around us, like an anthill sprawling deep underground, with elaborate passageways to thousands of other lives that you’ll never know existed, in which you might appear only once, as an extra sipping coffee in the background, as a blur of traffic passing on the highway, as a lighted window at dusk.

News from Home abounds with such glimpses of the anonymity of intimacy, and the potentially transformative relationship to otherness that it entails.

But what about this film so pricks me? It is not nostalgia for New York, or at least not exclusively so. There is one detail in the film that punctures me, flushing my own psychic frame with an almost unbearable sense of pathos. Suspended in a typically uneventful letter, the detail will mean nothing to you:

Dearest child, I received your letter and hope you'll write often. I think you’re happy in New York, so we’re happy too even though we do miss you. When will you be back? Everything’s the same here, but Sylviane’s home with the flu and I’m not very well …

For me the voice dissolves after this; the words no longer matter. The wound arrives in the name “Sylviane,” which is, I suddenly recall from Chantal Akerman’s obituaries, the name of the filmmaker’s sister. It is also, however, the name of my mother-in-law, who was born in a displaced person’s camp in France to two Polish Jews who were imprisoned in different labor camps in Russia after running east in an unsuccessful attempt to flee Hitler. After the war, they miraculously reunited in a displaced persons’ camp in Germany before moving to France, where they lived for a few years before immigrating to Montreal. There, in an unheated, cold-water flat in what is now my neighborhood, they lived for nearly a decade, waiting to immigrate to the United States. Fifteen years after the end of the war, they finally settled in Brooklyn, where my husband and I were both born, a short subway ride away from each other, although we wouldn’t meet until both of us had migrated elsewhere. For me, these and other peregrinations are embodied in the name “Sylviane.” For in the immediate postwar years in France, even Jewish refugees had to be named after Catholic Saints, and so my mother-in-law was named not after her own murdered ancestors, but after Saint Sylvie, the mother of Saint Gregory the Great, whose holy name is sometimes invoked by pregnant women in their prayers for a safe delivery.

Filmed from the deck of the Staten Island Ferry, the last shot of News from Home is a long take of the downtown skyline as the ferry pulls slowly away from it. Mesmerizing in its backward pull through the miasma of water and wind, this is an image of abandonment, of loss piling up upon loss. One of only two moving shots in the entire film — the other is of moving traffic shot from the back of a cab — this final shot reminds us that in spite of the film’s stillness, we’ve been moving all along, further and further away from ever being able to recapture the intimacy that we lost in our forced migration to the parched earth from the wet wilderness of the womb. Perhaps the final image captures what Svetlana Boym means when she uses the phrase “love at last sight,” a sensation that “strikes the urban stranger when that person realizes he or she is onstage, at once an actor and a spectator” in a life to which one will never fully belong. “Love at last sight,” Boym writes, “is the spasm of loss after the revelation.” But just because something has been lost in the past doesn’t mean it can’t be lost over and over again.

¤

Made at a vastly different moment in Akerman’s career, No Home Movie records her mother Natalia in the last years of her life. Yet despite all the time they spend together during Akerman’s periodic visits “home” to Brussels, the unspeakable remains unspoken. The aesthetics are amateur and the interactions quotidian. Although they may be embedded in every domestic ritual and conversational evasion, the traumas of history resist revelation.

For a film in which nothing happens, however, the intimacy is staggering. What I recognized in Akerman’s last film was an attempt to give form to the ineffable intimacy between mothers and daughters who are forced to confront the end of their time together. While No Home Movie expressed what I had failed to commit to canvas or paper while I cared for my own mother, the filmmaker’s subsequent suicide haunted me with its revelation of the psychic risks of engaging so directly with questions of mortality and kinship.

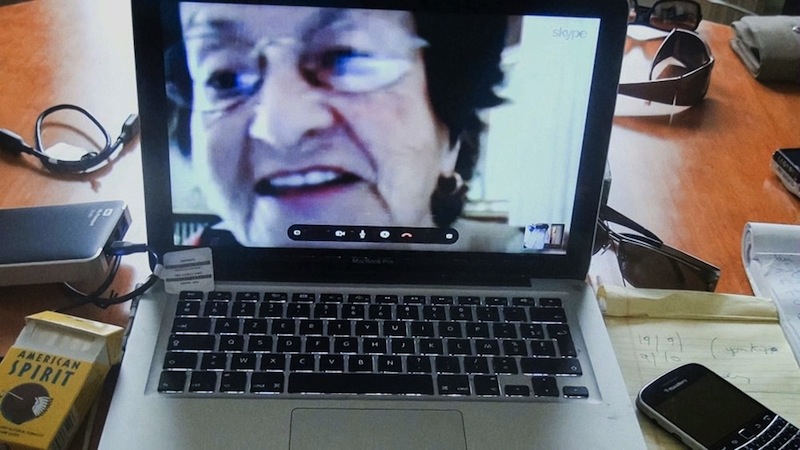

Characterized by amateur camerawork that both contrasts and resonates with the rigorous formalism of News from Home, No Home Movie is nonetheless just as unconventional a portrait. Released after her mother’s death in April 2014, No Home Movie records Nelly’s decline. In addition to stationary shots of Natalia’s apartment in Brussels, and some moving images that Akerman shot in Israel, the film includes recordings of Skype videos in which mother and daughter communicate across multiply mediated borders.

Whereas News from Home imagines the relationship to the mother through the prism of urban landscape, No Home Movie, like Jeanne Dielman, refigures this relationship through domestic architecture. Ordinary scenes of outdoor and indoor architecture are characterized by feelings of estrangement. These just happen to be the places where we find ourselves losing everything.

In No Home Movie, Akerman makes the decision not to make anything more picturesque than it is. Although certain aspects of Nelly’s apartment may seem familiar to viewers of Akerman’s “domestic films” from the 1970s — such as the seemingly ubiquitous tiled Belgian kitchen — the film offers neither the defiant formalism of Jeanne Dielman, nor the frenzied romanticism of Akerman’s early shorts. Forgoing use of a tripod, Akerman captured stationary shots of her mother’s apartment by stabilizing the camera on pieces of furniture, as if to suggest what life looks like from the point of view of a kitchen or a side table. Rooms are decorated with reclining chairs, Oriental rugs, tchotchke cases, and plants. Everything seems ordinary enough. Chantal Akerman is glimpsed padding around the apartment in an oversized pair of pink pajamas, and when she shoots the image of her computer on a makeshift desk, we find relief in its disorganization.

Yet Akerman’s penchant to shoot empty rooms through doorways suggests that as much as the apartment’s inhabitants seem at home in the space, they are forever hovering at the threshold between here and there, past and present. Rooms backlit by windows suggest an elsewhere that, when finally glimpsed, maintains its poker face. Strangers in a world reconstructed from unspeakable devastation, the Akermans peer in and perform their domestic tasks while remaining cognizant that even though a house may serve as a temporary refuge, it may never truly feel like home. All the while, the camera observes patiently, as if waiting for the apartment’s temporary inhabitants to pass through and return the rooms to a state of quietude. If there is no home, how can one make a home movie? This is just another way of asking how one can maintain a self in the face of the other’s imminent loss.

Meditating on the impending loss of both the filmmaker’s mother and her own already precarious sense of emplacement, Akerman distorts both home movies and documentary aesthetics to capture the textures of her mother’s life without ever disclosing the full horrors of her biography. “We thought we were safe here in Belgium,” Nelly recalls in one particularly candid moment in the film. “Then the Germans came.” “Like a knife through butter,” Chantal interjects. “No, not like a knife through butter…” Nelly murmurs, refraining from offering an alternative simile. For all its meanderings, this is not a film that can tolerate linguistic metaphor. Akerman documents indirection directly, or not at all.

Chantal Akerman has often recalled that her mother never wanted to speak directly about her experience in the death camp, or her forced march from it. “I asked her once to tell me more, and she said, ‘No, I will get crazy.’ So we could speak around, or after, or before, but the real moment, never. Not directly.” This indirection of language contrasts with what might be characterized as the typical impartiality of Akerman’s camera. Akerman herself attributed her penchant for shooting head-on to her obeisance to the Second Commandment, which forbids idolatry, or the making of graven images. “You mustn't prostrate yourself or you will be punished. That is why I always shoot face-to-face. So when you are watching my film, you are face-to-face. Therefore it is not an idolatrous image.”

Of all Akerman’s films, No Home Movie feels the least adorned, or the most straightforward. And yet the camera does not always offer her mother’s body to the viewer “face-to-face.” In one of the many scenes shot at mealtime in Nelly’s kitchen, Nelly’s back is to the camera, obliterating an image of both her and her daughter.

In other shots, the camera, most likely poised on a nearby piece of furniture, only manages to capture Nelly’s torso and the sound of her labored breathing as she moves somewhat unsteadily through a doorway.

The placement of the camera at an unconventionally diminished height lends itself to the quotidian nature of the scene. Yet it also acts as a distancing device, formalizing the means by which Nelly’s story resists full disclosure. When watching the film, there is a tacit understanding that this will be Nelly’s last opportunity to testify on camera. While she does refer to the events surrounding the Holocaust more here than she does in any of Akerman’s previous films, she does not approach its horrific core. When Nelly talks about her own mother, one could easily get the impression that she was able to join her daughter and granddaughter after the war in Belgium. This was not the case. Auschwitz is not only the structuring absence of this film but of all of Akerman’s work.

When I first watched No Home Movie, a few months after Akerman’s death, I was startled by how familiar it feels. It is true that I, too, witnessed the world with newly washed eyes in anticipation of my mother’s death. I recognized the way Akerman’s camera savored the preciousness of the banal as a way of preserving intimacy against the certainty of loss. But there was something else going on here.

In the first few years of my relationship with the man who is now my husband, we used to visit his grandmother on Friday nights in her one-bedroom apartment in the Sheepshead Bay neighborhood of Brooklyn. She too was a Polish-born Holocaust survivor who found herself, after the war, in a nation to which she never truly belonged. Cypora was not nearly as amiable as Nelly appears here, and her tiny apartment was hardly as luxurious. But something persisted across these superficial differences — a way of being that eludes words even as it confronts loss head-on. In the unadorned style of Akerman’s film, I recognized a modesty that was both a means of survival, and a refusal to be seduced by illusion. Despite the way Nelly’s bourgeois accoutrements contrast with Cypora’s notable lack of possessions, I recognized a similar way of occupying a house so that it never seems like a home. Between mother and daughter, mindless arguing about meals functions not as criticism but as a form of relief from the eternal burden of the unsaid. “I’m just an ordinary person,” David’s grandmother used to mumble, as she flicked away any discussion of the past with her gnarled fingers.

When I rewatch No Home Movie with my husband, he admits that he is moved by the film, but doesn’t note the wrenching similarities that I have observed. “My family was never that expressive,” he sighs. Recalling the tense silences of our Friday night Shabbat dinners, I am compelled to concur. I can’t remember a single time his grandmother ended the visit by saying, “I love you,” although love him she did.

Yet expressivity is not the overwhelming tone of Akerman’s last film. Many of the most expressive moments of Akerman’s film surprisingly arrive in guise of the Skype conversations she has with her mother. Struggling to hear the news her daughter transmits across oceans of distance, Nelly sits too close to the computer, obscuring her face in pixelated close-up. Chantal’s own face is often blocked by her video camera, which remains trained on the screen. Despite these awkward obstructions, however, mother and daughter exchange effusive declarations of love and can’t seem to bear to disconnect from each other. “Why are you filming me like that?” Natalia asks her daughter. “Because I want to show there is no distance in the world,” Akerman rasps in the smoker’s voice that many of us have come to consider among the most satisfying grains in the world.

The more that I reflect upon it, the more I am confounded by Akerman’s answer. Surely, she is too world-weary to attribute such utopian effects to any forms of digital communication; this too would be a form of simple idolatry. There is, after all, nothing but distance in the world. And yet, no matter where Akerman is calling from, her identity is forever entwined with her mother’s fate. Trauma runs through the blood and remakes the gaze. There is no distance — in spite of the fact that they are worlds and oceans apart.

In No Home Movie, the geographical and technological boundaries between mother and daughter catalyze an expressivity that otherwise remains ineluctable. As film scholar Alisa Lebow has observed, “It is the distance, in fact, that seems to allow their gushing intimacy.” Indeed, the only times either mother and daughter succumb to idolatry is in these suddenly unrestrained explosions of affection for each other. Looking back at the film soon after its completion, Akerman observed, “So much love is coming out of her, and I was not aware of that. […] I knew she loved me, but when I see that Skype moment, it's really like a love affair between us.”

¤

No such image of my mother exists. Aside from the few unwatched minutes of digital video that my husband shot of her reading my favorite childhood book, Sloth’s Birthday Party, so that she might virtually intonate to a grandchild who didn’t yet exist and whom she would never meet, we never overcame our grief long enough to objectify her on camera. The only cinematic image that remains of that most difficult interval is a short video entitled Malady that David made in the last year of my mother’s life. Other than my disingenuous painting The Last Euphoria, it was the only artwork that either of us managed to complete in the two and half years of her illness.

My mother never appears in Malady, which consists almost exclusively of a collection of waist-high views from various windows. As its title suggests, the film is about affliction, but in place of the afflicted body we get a house, or rather, an inaccessible house, whose only visible details emerge in the unmonumental thresholds between inside and out. Neither her body nor the room in which she suffers are visible within the film. Instead, we get metaphor piled on metaphor: illness as an architectural boundary, the window a lens through which we can barely see. Beneath the vibrant edge of a stained-glass panel, we see the slight rustle of pages dyed violet and crimson by its colors as the wind moves through a dirty window screen. This momentary disturbance, and the flashes of lightning that illuminate an otherwise blackened street outside, are the only evidence we have that the Aeolian harp of artistic inspiration has not simply vanished from this scene of quiet desolation.

In one of its most clichéd aliases, the cinema is a window onto another world. But what happens when a window become a threshold that cannot be traversed, a screen that separates us from other bodies? In Malady, there is always a screen mediating inside and outside, always a distance that cannot be crossed.

Glimpsed through a screen pixelated by wire mesh, the greens of the garden do not beckon so much as taunt. Mere feet away from where my mother sat, the garden was transformed into an impossible elsewhere, visible only through tarnished glass. Within the claustrophobic frame of the window, the clipping of a succulent suspended in rust-colored water is one of the few images of vitality to which we have access. All around the film’s modest apparatus, things are living and dying, yearning toward, and retreating from the light. But the motionless camera refuses an entry to the theater of suffering beyond its grasp. Instead of opening the wound and allowing us to palpate or suture it, the film keeps us at bay.

Malady is not a portrait of my mother per se as much as it is a testament to what we can’t talk about when we talk about intimacy. As David’s voice intones near the end of the film, as “we look at each other, our gazes pass through to something distant.” This is as close as we came to learning how to survive.

¤

Ara Osterweil is a painter, writer, and scholar whose interests extend to postwar art and cinema. Her writings have been published in Artforum, Camera Obscura, Framework, Film Quarterly, and Millennium Film Journal, as well as in the anthologies Porn Studies, Women’s Experimental Cinema, Body Worlds, and Taking Place. Her book, Flesh Cinema: The Corporeal Turn in American Avant-Garde Film, was published by Manchester University Press in 2014. You can find more of her paintings and writings at www.araosterweil.com.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

Waveforms and the Women’s March

Briallen Hopper on what we can learn from the Women's March.

A Church Full of Females: A New History of Mormon Women

As the title of Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s 2007 book affirms, Well-Behaved Women Seldom Make History — like Mormon women.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2017%2F07%2FImage-1-Osterweil-Last-Euphoria.png)