A Deep but Unstable Joy: Gazing at Agnes Martin

By Jane Yong KimNovember 5, 2015

Agnes Martin: Her Life and Art by Nancy Princenthal

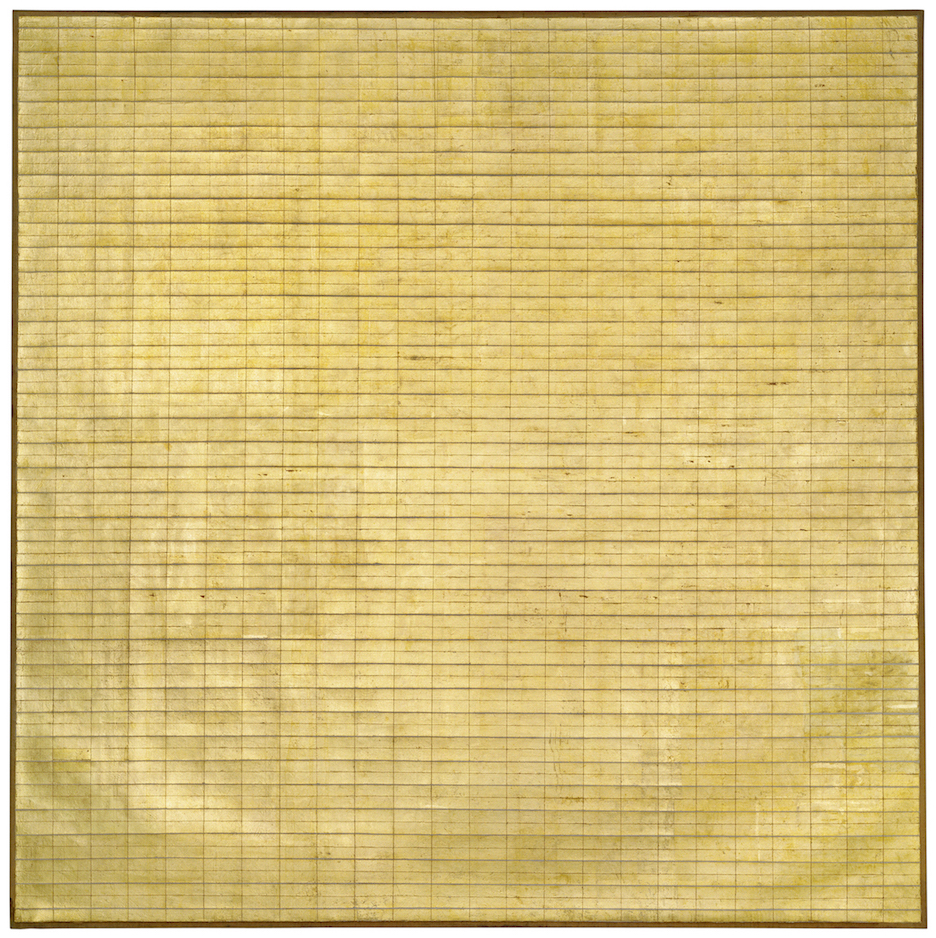

FROM UP CLOSE, the penciled lines of an Agnes Martin grid painting appear to waver, perhaps due to slightly unequal spaces between them or the way they occasionally bend to the weave of the canvas. From farther away, they tend to dissolve. As the eye is drawn to different parts of the canvas, attention might go to the darker lines or may rest on the background color — a flat, lightless gray, or a translucent, bleached-out red. The overall effect is mesmerizing, but destabilizing.

The artist has herself achieved a kind of hallowed standing, in which her life’s vicissitudes have taken on the mutability of myth. To female artists and art critics, Martin’s no-nonsense upbringing in the Canadian plains of Saskatchewan, itinerant teaching career, and late entrance into the art world initially made her a feminist role model who promoted an anti-patriarchal stance (even though she bristled when called a feminist, or for that matter, a woman). To others, Martin was a bridge between the robust and aggressively male abstract expressionist painters of the New York School and the harder-edged, impersonal abstraction that came to define a younger generation of Minimalists (although Martin identified more keenly with the former group and disputed her affiliation with the latter). To still others, intrigued by her tangles with mental illness and her abrupt move to the American Southwest just as her New York art career was budding, she represented the ultimate spiritual artist-hermit, led by a higher calling to shirk human comforts and the company of others in order to devote herself to her art.

Agnes Martin in her studio (smock, standing ¾ length)

on Ledoux Street, Taos, New Mexico, 1953.

Photo: Mildred Tolbert

The Harwood Museum of Art, Gift of Mildred Tolbert.

©Mildred Tolbert Family

Agnes Martin c. 1988 Galisteo, New Mexico

Photo: Donald Woodman

© Donald Woodman / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York

Nancy Princenthal’s attentive new biography of the artist, Agnes Martin: Her Life and Art, demonstrates how Martin consciously embraced and even exaggerated certain of these frameworks while eschewing others. Princenthal, an editor at Art in America and clearly a fan, has written an homage to Martin’s work and life, laying bare the plethora of contradictions with which any Martin scholar will necessarily contend.

One of the paradoxes central to Martin’s work was that, despite the mythology that surrounded her, she completely discounted the import of biography. As Princenthal writes, “[Martin] was unyieldingly committed to her vision and, with equal fervor, to refusing the claims of personal experience.” Her absolute dedication to the idea that art should be impersonal was one to which many in her artistic cohort, from Ad Reinhardt to Ellsworth Kelly, similarly cleaved. Thus it was that Martin hated any suggestion that her paintings — though sporting names like The Tree, White Flower, Cow, Red Bird, and Mountain — were representative of anything (a real-life object, an aspect of her lived life) other than what was in her head.

This strict separation of art and life can, as Princenthal acknowledges, give a biographer pause. Yet despite this willful self-erasure, her art was intensely and undeniably personal in its uncompromising vision, even if Martin may have rejected this characterization herself. This vision included a commitment to exhibiting her artwork, a prioritization that requires certitude and a firm sense of self, including allowing her paintings to be shown frequently alongside those of younger artists with whom she felt little aesthetic kinship, and inviting curators to trek out to the Southwest to see new work. Even her delight in reinforcing her reclusive image demonstrated a savvy for self-mythologizing. Explaining to a curator that she wouldn’t take questions from the audience after a lecture, she wrote, certainly with a measure of glee, “Tell them I’m a hermit.” The ways in which Martin navigated the layers of her artistic and personal life — creating and shaping stories about herself even as she discounted their importance — undoubtedly matter, even if they don’t cohere into an easy narrative.

Equal parts projection and lived reality, her reticent reputation has endured. The brilliantly funny Terry Castle notes in her essay “Travels with my Mother,” about a road trip with her mother to see Martin’s work in Taos, New Mexico, that photos of the artist in her studio shortly before she died were reminiscent of the writer Gertrude Stein, “stocky, impassive, the same Julius Caesar haircut — only dreamier, blue-eyed, more aerated somehow. Her emotional remoteness seemed absolute.” In an amusing twist, Princenthal expresses a similar sentiment — using the image of a face — about Martin’s work in a piece for The Brooklyn Rail: “There is little visual expression as tight-lipped about individual experience as the kind of reductive geometry Martin chose.”

The strict repression of individuality in Martin’s paintings notwithstanding, there exists in them a deeply human impulse that reaches for what she called the “renewal of memories of moments of perfection.” This was, to Martin, the function of art. Such renewed memories, she thought, should evoke abstract emotions such as joy and innocence (unlike what she considered more personal emotions, such as love or anger). Amid the copious lecture notes she took, she wrote of a sensory reaction to art, “If your sensibilities are awake you will respond. It will be a pleasant experience recalling happy times. You must see that no talking will help and that no defense is necessary.” Fittingly, she thought that the sublime rested not in the work but in the viewer’s response.

In this way, Martin’s work is somewhat akin to the sort of text that Roland Barthes described as “ourselves writing.” Barthes was describing the kind of text — and Princenthal is keen to call Martin’s graphite-lined paintings a type of text or presentation of unspoken thought — that jump-starts readers’ expectations and demands that they take an active role in the construction of meaning. Martin believed that the value of art, for both artist and viewer, was in its “expressive utility,” a conviction that Princenthal links to the pragmatism of John Dewey and in turn to Zen Buddhism. These systems of thought undergird the value Martin placed on experiential reality.

The comparison to Stein also goes beyond a similarity in their appearances and carriage. A student of William James, who was, like Dewey, a prominent pragmatist, Stein envisioned grammar (like truth and justice) not as fixed and unchanging but as determined by how we use it. “Suppose a grammar uses invention,” she asserts in How to Write, making a key link between structure and innovation — namely, questioning the point of the former without the latter. It makes complete sense that an artist whose building blocks were delicate lines, squares, and rectangles (each repeated over and over) would find resonance in the notion of a pragmatic, active grammar — one in which words, sentences, and paragraphs (all compositional units with which Stein tinkered) hummed at different frequencies. Here is Martin on her use of the square canvas:

My formats are square, but the grids never are absolutely square; they are rectangles, a little bit off the square, making a sort of contradiction, a dissonance, though I don’t set out to do it that way. When I cover the square surface with rectangles, it lightens the weight of the square, destroys its power.

Like Stein, Martin clearly saw the different frequencies of the compositional units she used and experimented with how they interacted. Her repetitive grid-making formed small rectangles of astonishing variation that served to profoundly alter the larger square canvases and innovated a kind of spatial grammar in which minute shifts in sequence, placement, and thickness spoke volumes.

¤

A much-repeated idea about a Martin painting is that it isn’t reproducible in print; the lines are too fine and the color gradations too subtle. There’s similar truth in the observation that textual descriptions of them, no matter how valiant, quickly become opaque and nonsensical. Here is how Princenthal describes The Tree, 1964, in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, and the work Martin often described as the first of her grid paintings:

The Tree is composed of twenty-four horizontal bands of narrow, vertical penciled rectangles, drawn over washes of white oil paint; bands of empty rectangles alternate with those occupied by quartets of faintly tingling vertical lines. At the bottom, the canvas rests on a band of empty rectangles; the topmost band is filled. The main vertical lines … are slightly heavier than the horizontal ones and the more so when the small rectangles’ internal verticals overlap the canvas-spanning ones, which they do irregularly.

The description begins fairly comprehensibly but ultimately requires that a reader hold in her mind — all at once — the geometry and placement of the bands and subsequent rectangles as well as the bands that are filled and the bands that are not, the lines that are heavier and lighter, and the larger and smaller rectangles. It’s a mind-boggling enterprise. In order for the painting to make sense, she must retain all the disparate parts in her head, much like a composer must keep the various parts of a symphony in her head.

Interestingly, this is exactly how Martin began her paintings: she saw visions of them, complete in her head, and then executed them on 6’ by 6’ square canvases. It speaks to her mental acuity that she was able to see and then translate these visions into pencil and oil (or acrylic) on canvas. The method (for the grid paintings, at least — her work varied considerably but she was best known for these) was always the same. Two tapes determined the separation of the individual grid lines; a T-square ruler set against them would guide her pencil or brush. For the lines, she used either graphite or colored pencils. “Up close,” Princenthal writes, the completed grid lines “form a code, a community, a hive.”

Agnes Martin, Friendship, 1963,

Incised gold leaf and gesso on canvas, 72” x 72”

The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Gift, Celeste and Armand P. Bartos

© 2015 Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

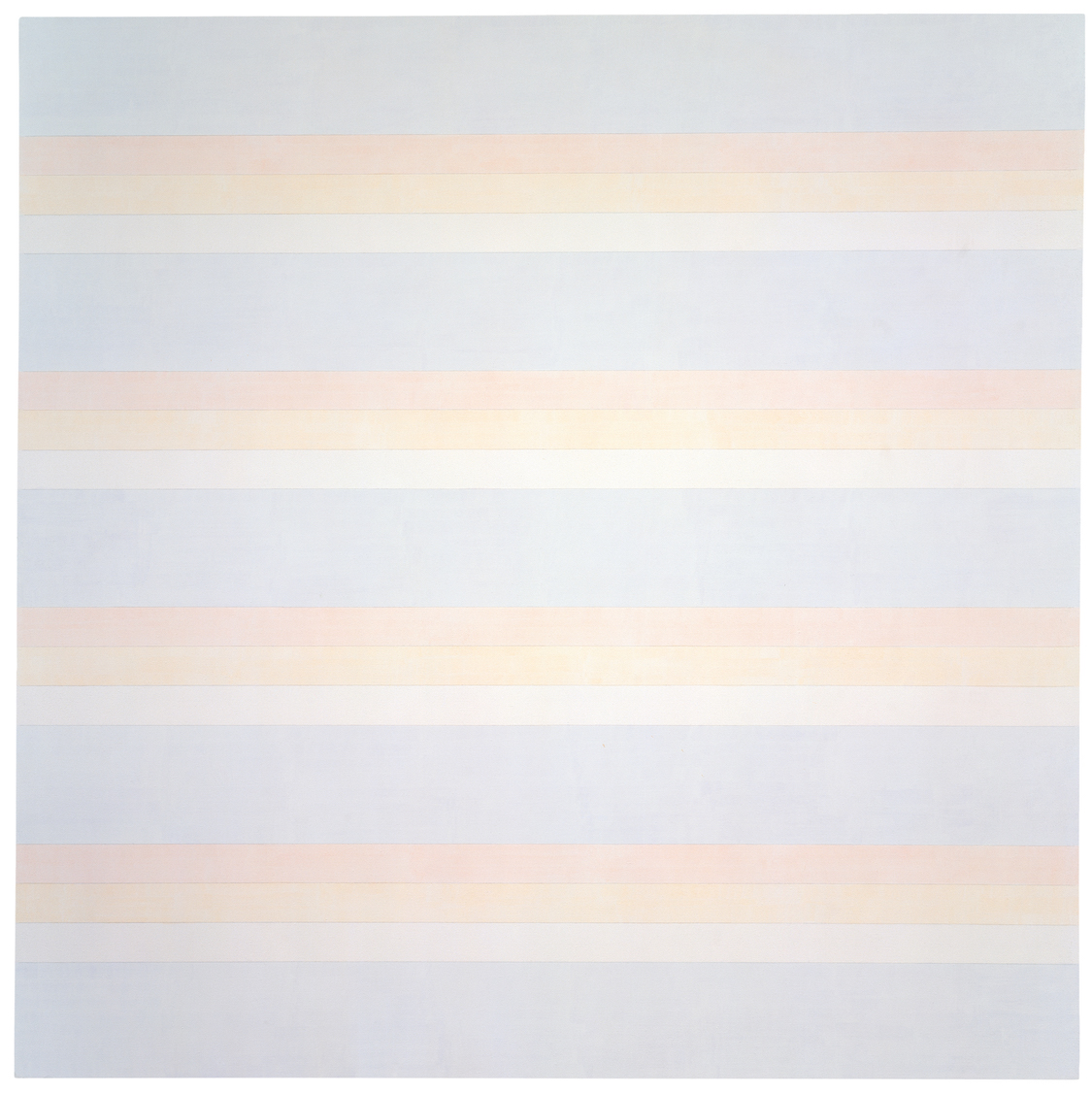

Agnes Martin, Untitled #2, 1992, Acrylic and graphite on linen, 72” x 72”

Photograph by Gordon R. Christmas, courtesy Pace Gallery

© 2015 Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Martin also suffered from paranoid schizophrenia, which manifested as blackouts or trances and auditory hallucinations, though Princenthal makes it clear that the voices she heard — and which occasionally told her what to do, including recommending that she not buy land — were different from the mental images that inspired her paintings. Part of the lore around Martin stems from her sudden departure from New York City, beginning a period of several years during which she ceased to make art. Though the common explanation is that she was fed up with the city’s art scene, Princenthal suggests that she left the city — and the Coenties Slip area of downtown New York, where she lived and worked among a cadre of like-minded artists including Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Indiana, and Jack Youngerman — for a combination of financial and mental health reasons. (She may have been kicked out of her lodgings and was hospitalized in Bellevue shortly before leaving New York.) Princenthal is both protective and assiduous in her research on this aspect of Martin’s life. She acknowledges the seriousness of Martin’s mental health struggles but diligently ensures that her life doesn’t fall into the narrative trap of the mentally beleaguered artist who heard voices that guided her paintings — which could prompt the sort of curious voyeurism that might plague the saintly girl who is said to miraculously weep diamonds. In other words, Martin was able to do her work in spite of these difficulties, not because of them.

Indeed, it is clearly impressive that, through these struggles, Martin was able to so rigorously pursue an artistic practice. Following the productivity of her Coenties Slip years, she spent much of the rest of her life in New Mexico — including several years atop an isolated mesa outside the small town of Cuba, New Mexico, where she mostly did not paint, and, after that, in the towns of Galisteo and Taos, where her productivity resumed. Because of the discipline required to create each of her paintings, the process functioned as endurance art, with each canvas a sort of test. Upon execution, it became, Princenthal seductively suggests, “an announcement, perhaps, of a problem distinctly apprehended, if never conclusively resolved.”

Martin exerted tremendous effort to produce her art, and viewers of her work are asked to perform a reciprocal struggle, to demonstrate a kind of loyalty to the act of viewing. An anecdote from art critic Jill Johnston illustrates the extent to which Martin focused on the viewer’s experience. She recalled:

looking at agnes’s paintings with agnes was a quiet concentrated ceremonious ritual … she traversed from the point in her loft where the paintings were stashed to the spot right next to the door where she showed them ... when she reached the showing place next to the door there would be a certain gesture of hiking the work with her foot under the canvas up into position on the nails sticking out of the wall. then she would sit down next to you and contemplate the work with you and wait.

Princenthal calls attention to “the extended moment of quiet sitting,” apparently a common experience for friends and visitors. The powerful image of an artist sitting next to someone viewing her art — not in front of, or behind, or through a two-way mirror on the other side of the room — underscores both the deliberate, unhurried nature of the moment and the parity between the two bodies. Artist and viewer play different but vitally important and responsive roles in creating that experience.

How have others described seeing the paintings in person? Reflecting on a room filled with Agnes Martin paintings from the 1990s (the paintings are striped, but not gridded) at the Harwood Museum of Taos, Castle describes it as “full of faintly pulsing energy currents” with “a promise of contact.” After some examination, “her pictures begin vibrating on the retina with strange energy, flipping gently back and forth between metaphysical registers like one of Wittgenstein’s playful visual paradoxes.” Holland Cotter, reviewing a retrospective of Martin’s work at Dia:Beacon in Hudson, New York, for The New York Times, compared each of the paintings to “a clarified experience of reality.” Meanwhile, Princenthal, in a short epilogue, describes revisiting as an adult the first painting of Martin’s she saw as a teenager — The Tree, 1964 — at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. At first, none of the magic appeared and she saw only pencil lines and paint. It was only on a subsequent visit that it came alive for her again, transforming into a “buffer for the kind of shattering, screaming beauty that may swallow you whole.”

A promise of contact. A clarified experience of reality. A buffer for a beauty that may swallow you whole. These phrases describe an extended moment of sublimity — and as such, articulate beautifully the raison d’être of gallery and museum spaces. Standing in front of a Martin painting makes for a profoundly human experience. It’s also the reason that Princenthal’s untangling of Martin’s knotty biographical material is ultimately more useful than the close readings of her work that comprise significant chunks of the book. Princenthal would surely agree that, though the latter are thoughtful tributes to a great artist, there is no better tribute than to inspire a new generation to confront Martin’s work. By sorting through and parsing fact and myth, separating wheat from chaff, the book helps to tease apart her life in all its contradictory glory. She was a fascinating individual, driven equally by internal discipline and a deep if intermittent sense of community, by penurious necessity and the flux of aesthetic praxis. But words will only take you so far. The recent retrospective of her work at the Tate Modern in London, simply titled Agnes Martin, will travel next year to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Guggenheim Museum in New York, affording opportunities for direct communion with her work.

At a moment in time when an image that cannot successfully be retweeted or Instagrammed can seem nonexistent, Martin’s paintings demand the ludicrous: an in-person interaction with a painting that won’t reproduce digitally. Cotter has surmised that Martin’s work has not been the subject of much talk since her death in 2004 due to this irreproducible quality. At a lecture on her work, he said that “one of her graphite-drawn paintings was projected in a PowerPoint display onto a large screen, and, to all appearances, there was nothing there: just an unmarked white square. The drawn lines were too faint to be seen.”

His frustrating conclusion is that “in a digital age, [Martin’s work] has disappeared.” Something similar could be said of Gertrude Stein’s writing; in a sound-byte age, her experimentations with form don’t reproduce in any digestible format. One must fully immerse oneself in her difficult, repetitive, and questioning texts in order to engage with her pedagogy of epistemic writing — there is no shortcut. But this leads to the flip side of Cotter’s reading, which is that Stein’s and Martin’s are art forms that require attentive readers and viewers in order for the work to survive, grow, and enhance in meaning. “The business of response is a delicate, willed operation, a deep but unstable joy even when it succeeds,” writes Princenthal at the conclusion of her book. Indeed, there’s no guarantee of any type or size of response. But when contact is made, when one of Martin’s paintings grips you and expands for a moment, almost painfully, your capacity to feel connected with the world — that moment is simultaneously familiar and beyond description.

¤

LARB Contributor

Jane Yong Kim is an editor and book critic who has contributed to Bookforum.com, The Paris Review Daily, BOMB, and Al Jazeera America, among other outlets. She lives in Queens and tweets at @janewhykim.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Feminism of Resilience: Shirin Neshat at the Hirshhorn

The exhibition "Facing History: Shirin Neshat" provokes a more complex conversation about Iran and the United States than has been possible in...

Tiny Guides on the Last Adventure: Doll Play in the Work of Jennifer Wynne Reeves

Jennifer Wynne Reeves.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!